Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

First of two parts

Supporter Spotlight

Sailors have long believed that it was bad luck to leave port on a Friday, and worse should it be Friday the 13th.

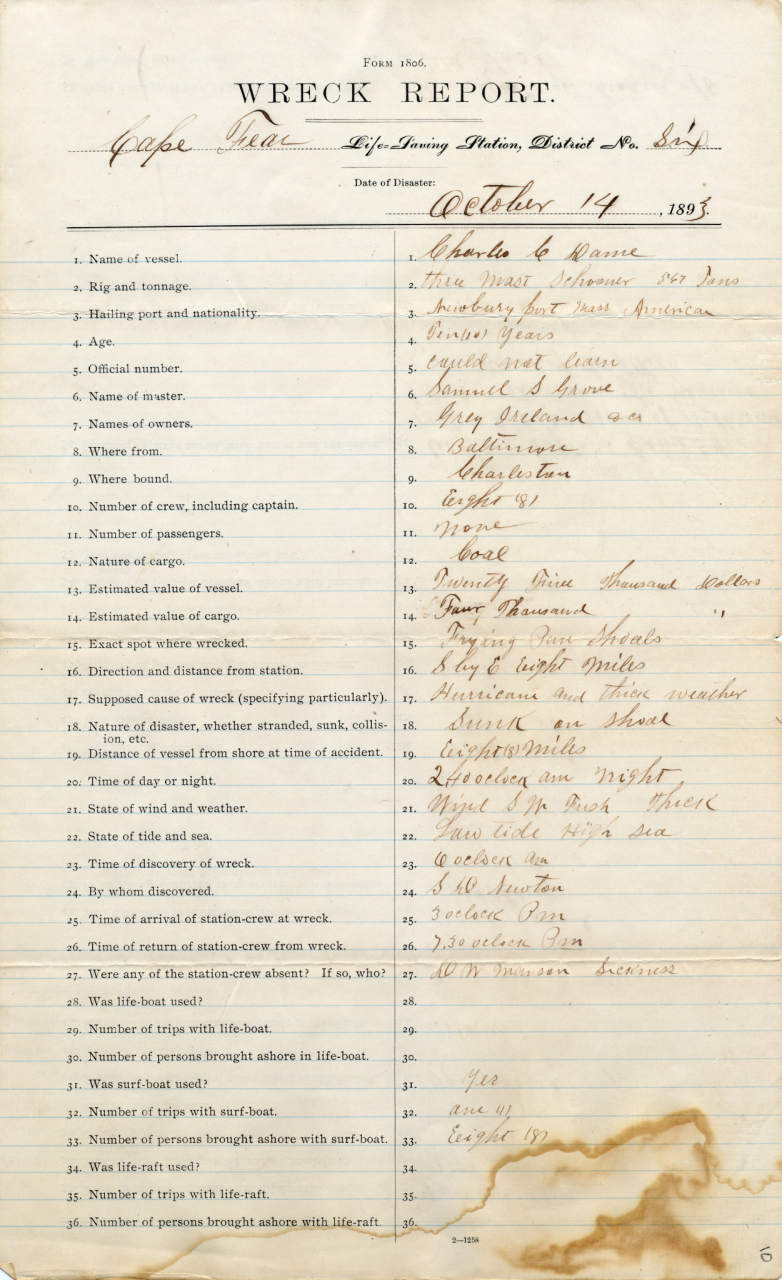

For Samuel S. Grove, master of the three-masted schooner, Charles C. Dame, attempting to arrive in port on Friday the 13th turned out to be just as unlucky.

Grove’s elegant, dark-hulled 567-ton schooner was built in 1882 at a prolific shipbuilding yard on the Merrimack River and named for a prominent civic and Masonic leader of Newburyport, Massachusetts.

The ship’s name itself may have brought bad luck. The original Charles C. Dame was lost in “a terrible gale” off North Cape Breton Island in 1873. The ship’s entire crew of 18 men perished.

Two years after the schooner was launched, the second Charles C. Dame stranded on the beach off Metedeconk River, New Jersey, in 1884. It took 11 months to get the ship refloated.

Supporter Spotlight

In October 1893, the same ill-fated schooner was off the North Carolina coast racing toward Charleston from Baltimore with the cargo hold filled with coal.

The vessel, after rounding Cape Lookout, scudded along on a broad reach before a strengthening east-southeast breeze, making good time toward its destination.

The friendly wind was a siren’s call, however, beckoning the Charles C. Dame toward an awful fate. Within hours, immense swells rising from the southwest grew ever larger and the sky beyond became ominously darker. What Grove and his crew of seven men did not know but may have surmised — they were heading directly into the turbulent gyre of a tropical tempest.

Grove gambled that with haste and luck they might reach the relative safety of Charleston harbor before the worst of the storm reached them. He should have known not to wager against Mother Nature.

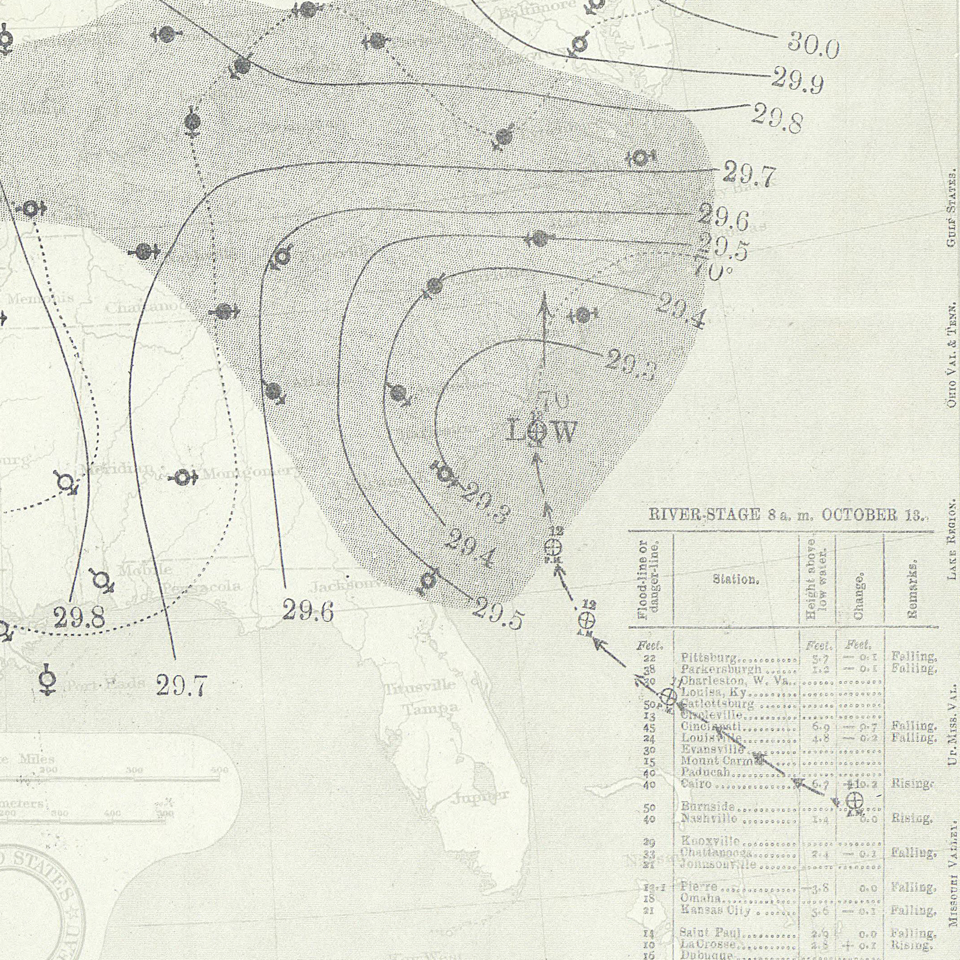

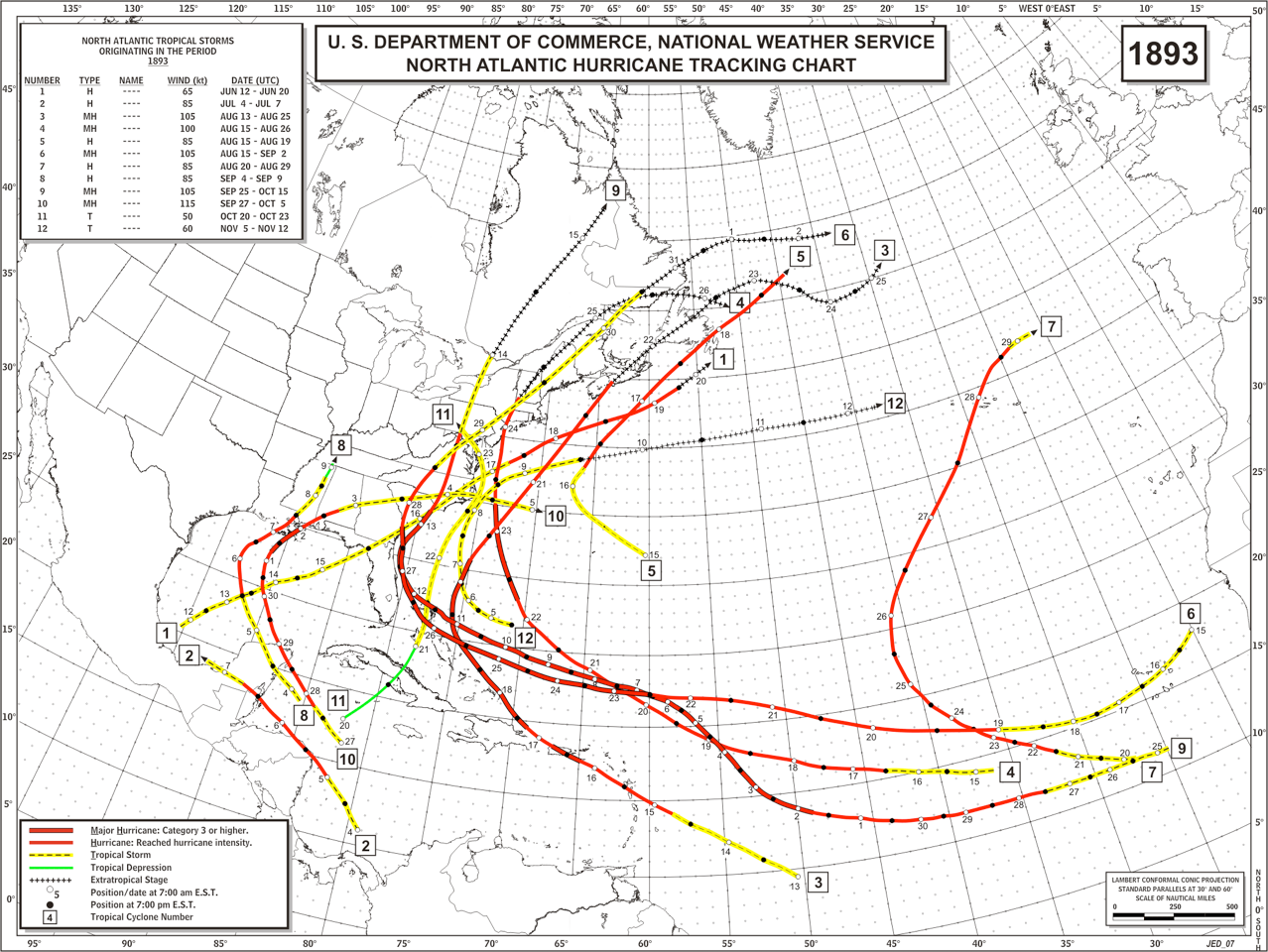

At that moment on Friday, Oct. 13, 1893, the ninth tropical cyclone of the year, a fast-moving hurricane with sustained winds topping 120 mph, which today would be considered a Category 3 storm, arrived off the South Carolina coast from the Bahamas. Around daylight the eye was passing east of Charleston at about the same time as the Charles C. Dame was preparing to enter the port.

The schooner’s sails were blown to tatters and was ejected out of the storm’s eye wall like a toy, propelled uncontrollably under bare poles to the northeast. Ahead lay Frying Pan Shoals.

The Atlantic storm season of 1893 was not forgotten for many years. It caused unprecedented destruction to life and property.

“The memory of the oldest inhabitant fails him when he tries to recall such another year of storms,” wrote Joel Chandler Harris in Scribner’s Magazine the following year. “The records show no parallel to it.”

The deadliest of the hurricanes was the sixth storm, better known as the Sea Islands Hurricane, which made landfall late in the evening of Aug. 27, 1893, north of Savannah. Two thousand people, mostly poor families living on the low-lying barrier islands of Georgia and South Carolina drowned. More than 30,000 were left homeless and destitute.

On Aug. 28, 1893, the hurricane entered the Tar Heel State. Off the Brunswick coast, eight ships and their crews and passengers were later determined to have vanished without a trace. When the curtain of darkness, driving rain and wind-blown fog finally lifted as the hurricane passed to the west of Cape Fear, numerous disabled vessels were revealed.

Over a period of nearly 60 hours, without sleep, food or even drinking water, the keepers and volunteer crews of the Oak Island and Cape Fear U.S. Life-saving Stations valiantly rescued, provided first-aid, food and clothing to shipwrecked survivors of the storm. In David Stick’s seminal book, “The Graveyard of the Atlantic,” the story of the rescues and super-human effort of the keeper of the Oak Island station were immortalized in a chapter titled, “The Long Day of Dunbar Davis.”

But Dunbar Davis, no doubt an exceptional hero, was just one of a dozen or more Cape Fear area lifesavers who came to the aid of shipwreck victims during that horrible hurricane year. John Watts and his crew of Cape Fear Station had their own long day.

The Cape Fear station, built in 1883 on the island’s east beach, was among the first to feature a fully enclosed watch tower atop the roof. While it was still dark on the morning of Oct. 14, 1893, 29-year-old Sam Newton of Southport wearily climbed the narrow stairway leading into the precariously perched watch room.

It had been a sleepless night for the station crew as the men were certain that their services would be needed in the morning. All night the stoutly built building trembled and the window panes vibrated in the violent gale-force gusts of the passing storm.

In the tower the windows were blurred by streaks of rain. The sky begrudgingly began to barely brighten. Newton began sweeping the horizon with the station’s marine field glasses but visibility could not have been worse. Then, at 6 a.m. he saw it, on the very edge of the horizon frequently occulted by billows of spindrift, the barely distinguishable dark hulk of a vessel to the south-southeast on Frying Pan Shoals. It was not moving!

Newton tumbled down the steep stairs into the bunk room below. The alarm was sounded and the remaining crew members roused from their fitful sleep. Above the roar of the storm, 38-year-old station keeper John L. Watts shouted the assignments and then went outside to raise signal flags to alert Dunbar Davis and the Oak Island Station about 5½ miles to the west across the Cape Fear River that there was a ship ashore — “Cape Fear Station requires assistance,” the flags spelled out. There was no time for coffee or breakfast, not while lives were at stake in the offing.

Records have not preserved what Watts told his men that cold autumn morning but, no doubt, he reminded them that they had chosen their line of work and it was no time for timidity. Under similar circumstances at another North Carolina life-saving station, the keeper ordered each of his men before setting out on a similar ocean rescue to sit down and quickly write their last will and testament. Life-saving was not a job for the weak of heart.

One Cape Fear crew member, D. W. Manson, was absent due to sickness. The other full-time men are believed to have included number one surfman John C. Price, Samuel D. Newton, John W. Moore, J. W. (Wesley) Smith, Robert W. Davis and James Alexander Pinner.

Life-saving service regulations allowed station keepers to choose the most experienced able-bodied watermen in their communities. However, they were not permitted to employ their immediate relatives in order to “countervail the quite natural inclination of keepers to provide situations for their near kinsmen, even to the serious detriment of the strength and morale of the station force.”

Watts and his close friend, keeper Dunbar Davis, circumvented that regulation by hiring each other’s’ brothers. Robert, on Watts’s crew was Dunbar Davis’s brother, while Davis had Watts’s brother, Crawford, serving at Oak Island.

Watts was worried that he needed a full crew of eight due to the severity of the conditions. He turned to Moses Stepney, possibly the station’s African American cook who had participated in a surfboat rescue to the schooner Three Sisters during the August storm, and offered him the standard U.S. Life-Saving Service wage of $3 per day to join the crew. Stepney bravely accepted but there was no guarantee he would ever make it back to claim his reward.

The heavy wooden doors at the seaward end of the Cape Fear station were rolled back and the 27-foot-long, 1,000-pound Beebe-type, self-bailing surfboat emerged from the boat room atop its wagon. The men, hitched to the wagon like mules, dragged the boat and wagon down its wooden ramp and onto the soft wet sand of the beach.

Aboard the boat were cork life preservers, a heaving line, bailing buckets, signal rockets, six rowing oars and one 20-foot-long steering oar with which the station keeper, now called “Captain Watts,” would operate using every ounce of his strength. Typically, crews would put to sea so quickly they did not have time to gather and stow fresh water or food.

For the men of life-saving stations, the most dangerous of any method of rescue was an open water surfboat rescue during storm conditions. The risks even greater when rescues were attempted in and around North Carolina’s three tempestuous shoals at Cape Hatteras, Cape Lookout, and Cape Fear.

Ships that grounded on these shoals, often miles from shore, were typically surrounded by a field of dangerous jetsam — spars, timbers, wooden casks, and deck cargoes all tangled in a nightmarish web of tarred rigging, tossing about on the waves and able to ensnare or put a hole in the bottom of a surfboat.

In such conditions, captains of lifesaving crews faced their ultimate challenge, having to maneuver their boat through the lethal debris field to get close enough to a disintegrating ship before its crew all washed away into the merciless sea.

Huge, rolling waves would heave the ship and lifeboat in wild, disparate arcs, up and down, canting at opposite angles. Amidst the deafening roar of the storm, lifesavers and shipwreck victims shouted as they attempted to coordinate their desperate efforts, as wind-driven rain or sleet, like airborne nails, blinded the lifesavers who were soaked and chilled to the bone.

Upon the approach of the surfboat, the captain of a shipwrecked vessel was required to yield all authority to the captain of the lifesaving crew. The U.S. Life-Saving Service provided all American merchant vessels with small booklets with strict instructions in the event that they foundered at sea: “Any headlong rushing and crowding should be prevented, and the captain of the vessel should remain on board, to preserve order, until every other person has left. Women, children, helpless persons, and passengers should be passed into the boat first.”

At an opportune moment, the lifesavers would heave a line aboard the wreck, all the while working their oars with their bloody, callused hands to keep their little craft from being crushed by the wounded, lurching leviathan.

These were the mental images, and of their loved ones back home, that occupied the Cape Fear station lifesavers’ minds as they helped their comrades trudge through soft sand, dragging the surfboat down to the beach to go to sea.

Official U.S. Coast Guard photos of surfboat launchings posed during pleasant weather –when such photography was conducive –utterly fail to convey the lifesaver’s formidable and intimidating mission.

Often facing a turbulent bulwark of breaking waves crashing before the beach through which they reluctantly had to launch their stalwart little craft, lifesavers had no choice whether or not to attempt a rescue.

According to the regulations of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, “The statement of the keeper that he did not try to use the boat will not be acceptable unless attempts to launch it were actually made and failed…”

Across the Cape Fear River, the heretofore indomitable Dunbar Davis and his crew attempted to launch their surfboat into the raging seas and failed. Twice. They implored the captain of a local tugboat to tow their surfboat beyond the bar of the inlet.

The tugboat captain refused — “the weather was too tempestuous,” he said. It seemed that no one could possibly breach the mountainous seas. As this was happening, the Oak Island range lighthouse was utterly obliterated by the storm.

Back at East Beach, standing amid clouds of sea foam, the undaunted Cape Fear crew slid their surfboat off of its wagon as waves knocked them sideways and undermined their footing in the swirling sands. They shoved the boat into the turbulent water, and quickly jumped aboard. The time was 7 a.m.

No doubt, the lifesavers’ hearts were filled with anticipation, apprehension, and nervousness. Beyond lay the outer bar and mountainous combers, curling and crashing with a full-throated thump, and wave crests whipped into blinding plumes of spray.

The oarsmen faced their captain or helmsman, their backs to the wall of water through which they had to penetrate. They could only imagine what horrors lurked behind them. Meanwhile, Capt. Watts maintained his expressionless countenance lest he convey the slightest anxiety to his crew. “Steady, boys, steady. Now! Stroke! Stroke! Stroke!” the captain may have shouted as he spotted a momentary weakness in Neptune’s defenses. They were off.

The Cape Fear surfboat rose up the incoming wave, which lesser men would hardly call a weakness, ever steeper, higher and higher, until the bow of the boat was nearly 20 feet above its stern, and in a spectacular explosion of spray and foam, the sturdy craft broke through to the wave’s other side and fell onto a trough and the open ocean. The Cape Fear Life-Saving Station crew’s ordeal had only just begun.

Next: A daring rescue