This weekend marks the anniversary of Hurricane Dorian’s landfall on the North Carolina coast, which resulted in devastating flooding on Ocracoke Island. Guest columnist Peter Vankevich, copublisher along with Connie Leinbach of the Ocracoke Observer, has collaborated with Coastal Review Online in publishing this look at how the storm has changed life for island residents.

OCRACOKE ISLAND — To modify a cliché, there is truth when saying “Ocracoke has weathered the storm … again.” Hurricane Dorian, the most recent hurricane to hit the island, could modify it with “barely.”

Supporter Spotlight

Ocracoke’s community has withstood major hurricanes over the centuries, sometimes in sensational fashion.

In early September 1913, a hurricane struck eastern North Carolina. A national news dispatch on Sept. 4 on that storm reported that all 500 residents on Ocracoke had perished. The story was based on someone seeing 30-foot waves in the Pamlico Sound.

To the credit of the press back then, the news report was quickly walked back and, in fact, not a single fatality occurred on the island. Nevertheless, that unnamed hurricane caused substantial damage throughout the eastern Carolinas. Erik Heden, the warning coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Morehead City, pointed out that the 1913 storm was classified as a Category 1 event, which proves that category numbers are not a sole reliable indicator as to what a major storm can do in causing devastation.

“The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale measures wind speed only,” said Heden. “It doesn’t factor in storm surge and rainfall, which can have devastating impacts as we saw with Dorian.”

Ocracoke has withstood many powerful hurricanes, with names such as Gloria, Isabel, Alex and Matthew since 1953, the year the National Hurricane Center began using a preselected list of women’s names for Atlantic Basin storms. In 1979 alternating men’s and women’s names for storms began. Prior to that, there were other destructive storms, notably the Independence Hurricane of 1775, the San Cirioca Storm in 1899, the Hurricane of 1933 and the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944.

Supporter Spotlight

The many details of the impact of Dorian which closed the island to visitors until Dec. 2, are too numerous for this story but many more are available from the Ocracoke Observer.

Here are some of the highlights:

- Dorian had a profoundly harmful impact on Ocracoke, causing a deep trauma — physical, mental and economic.

- By the time it made landfall on Hatteras Island, just above Ocracoke, on the morning of Sept. 6, it was far from being the most powerful, “just” another Category 1, with peak winds of about 90 mph.

- Dorian arrived well credentialed. It formed Aug. 24, 2019, and quickly rose to an extremely powerful and devastating Category 5 hurricane with peak winds at 185 mph. It is the most intense tropical cyclone on record to strike the Bahamas and is regarded as the worst natural disaster in the country’s history. The United States waited nervously as it headed west. Dorian skirted the Atlantic Coast of Florida then moved northward, causing relatively minor damage until reaching Ocracoke.

- Dorian struck at night on Sept. 5, and on Sept. 6, around 7:30 a.m., a 7.4-foot storm surge quickly tore through the village. Amazingly, there was no loss of life from this storm.

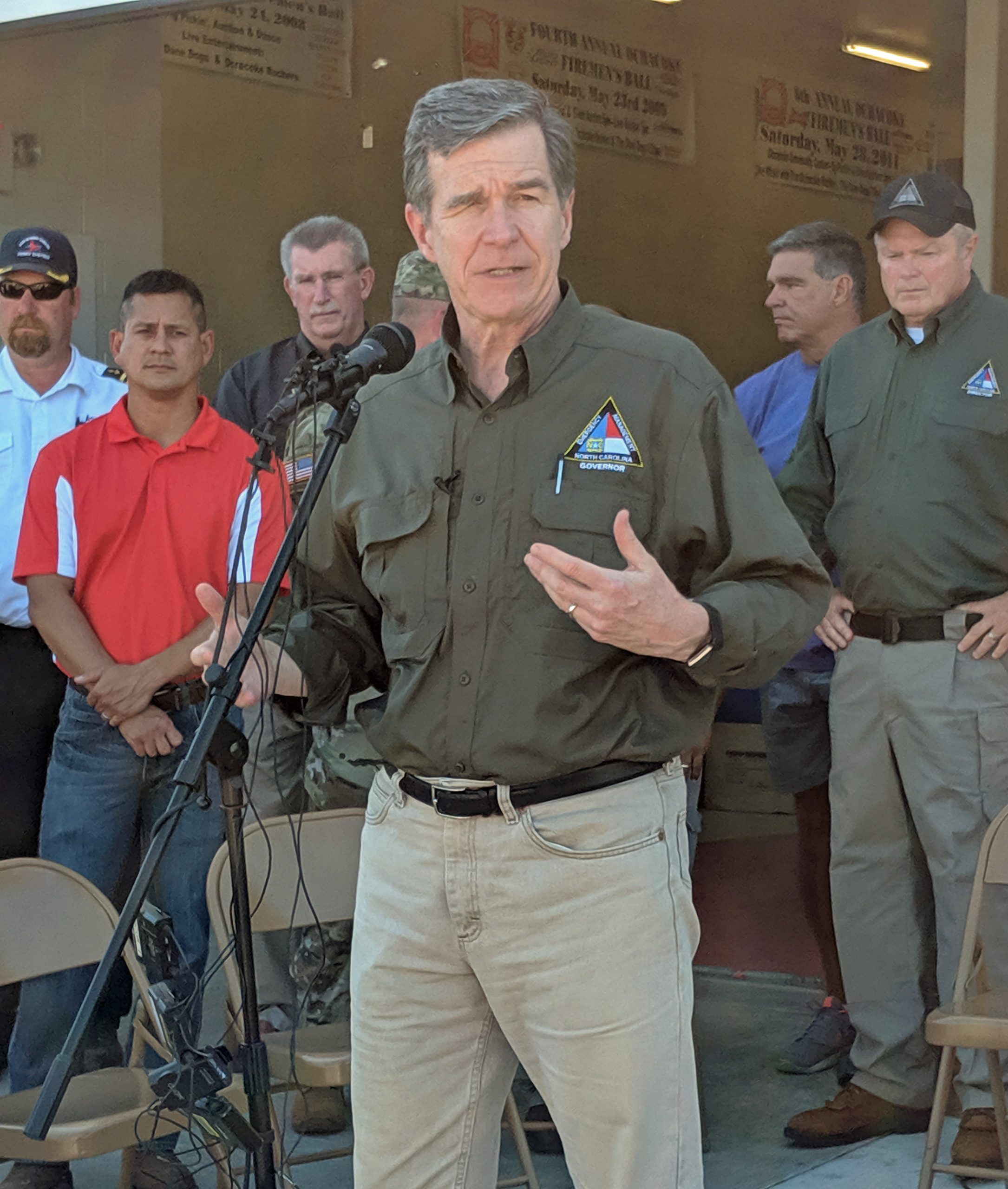

“There is significant concern about hundreds of people trapped on Ocracoke Island,” Gov. Roy Cooper said in a press conference that day. “There are rescue teams ready as soon as they can get in.”

Cooper visited the island the following day to get a first-hand look.

Even before the storm had departed, several islanders took to their skiffs and piloted through the village making many heroic rescues of folks unable to get out of their homes.

It quickly became obvious that the assistance needed would be substantial and long. For various times, the only grocery store, the bank and health center were closed, and the electric power was down and an unprecedented warning went out that lasted for a few days to boil tap water before drinking or cooking with it.

Dorian’s high waves breached N.C. 12 at the north end, cutting off access to the Hatteras Inlet ferry terminal.

Ocracoke School flooded and classes were canceled. School officials worked feverishly to find alternative locations, ultimately using North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching, or NCCAT, facility, Ocracoke Child Care, and the upper floors of the school’s elementary section. But it would take a month before students could return to class. These locations that would last until COVID-19 on March 14 caused a shutdown for all state school buildings.

As the floodwaters ebbed, officials mobilized the Ocracoke Volunteer Fire Department as a command center. Many islanders showed up to volunteer and were quickly put to work, others arrived requesting assistance, noting their homes were destroyed or trees had fallen onto their houses.

The Ocracoke Control Group, Office of the County Manager, and Hyde County Emergency Management met to develop and implement a plan to deal with the disaster.

Ocracoke was not abandoned. In fact, it seemed like the whole state mobilized to provide assistance and donate goods. A host of state and federal partners soon arrived, including the National Park Service, the North Carolina Department of Transportation and its Ferry Division, the governor’s office, state Emergency Management and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The North Carolina Office of Emergency Medical Services set up a field hospital outside the health center, which was badly damaged and would take a few months to reopen.

Residents of Carteret County and mainland Hyde County filled their boats and delivered much-needed emergency supplies. Donated food, cleaning products and other supplies poured in via the ferries and filled the bays of the fire department with the firetrucks parked across the street.

The village quickly took on the appearance of a disaster zone with debris from flooded houses, many of which would be demolished, and downed trees lined the streets. Dozens of totaled vehicles were placed along the road, especially north of Ocracoke.

The National Park Service permitted the material to be taken to the parking lot of what is locally known as Lifeguard Beach and vegetation at a site near the campground. Both locations were massive, causing locals to declare the Lifeguard Beach parking lot as the highest point in Hyde County.

Ocracoke’s county commissioner, Tom Pahl, the keynote speaker at the Outer Banks Community Foundation’s annual meeting and luncheon on Feb. 20, noted that more than a third of the buildings on Ocracoke were severely damaged; 88 of 105 businesses sustained significant damage; hundreds of cars and trucks were totaled and 3 miles of road at the island’s north end destroyed, taking several weeks to repair.

Many individuals and organizations volunteered to help, including the American Red Cross and the faith-based Salvation Army, Samaritans Purse, North Carolina Baptists on Mission, and the United Methodists Committee on Relief (UMCOR). These groups went to peoples’ homes and removed downed trees, ripped out water-soaked insulation and performed many other tasks.

One of many heroes is the Outer Banks Community Foundation. It set up the Ocracoke Disaster Relief Fund and raised more than $1.2 million in contributions from about 6,000 donors. Organizations and individuals from all over the region and the country also sent contributions to the school and two churches.

Throughout the fall, there were many fundraisers, including the performing artists of the Ocrafolk Festival at the historic Carolina Theatre in Durham, and a lemonade stand set up by a 6-year-old near the North Carolina Seafood Festival in Morehead City, that got onto social media and raised nearly $9,000 for the school.

The governor returned Sept. 23 with several of his secretaries and top staff and they spent the day listening to the islanders and touring the village.

To pile on, a mid-November storm pummeled the Outer Banks with two days of sustained winds of more than 30 mph and gusts much higher that again wreaked havoc on N.C. 12 and caused the ferry system to suspend operations, resulting in a delay in reopening the island, which finally happened Dec. 2.

As the islanders struggled to return to homes and reopen their businesses, people started looking forward.

Hurricane Dorian caught the attention of Whitney Knollenberg, assistant professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management at North Carolina State University. She focuses her research on the role of policy and planning and sustainable tourism development. She had previously done a study on Ocracoke’s tourism economy that was funded through North Carolina Sea Grant as part of their community collaboration research grants program.

“Reading the news about Ocracoke, I realized that Dorian would have a long-term impact on the island’s economy and a follow-up study was needed,” she said. “It (Dorian) really stood out to me as an example of an event that is going to continue to happen in places like Ocracoke, which are reliant upon tourism, and we are going to have to figure out how to address these types of changes.”

Knollenberg and three colleagues have received a grant from the National Science Foundation to identify the available information and resources for community leaders to make policy and planning decisions. The scope of her study has been expanded to include the COVID-19 pandemic.