WILMINGTON – A University of North Carolina at Wilmington laboratory made history this month by spawning in captivity an endangered coral that once thrived in shallow reefs in the Caribbean.

Researchers at the university’s Center for Marine Science are the first to spawn two species of coral, including Orbicella faveolata, also known as mountainous star coral, in a laboratory.

Supporter Spotlight

Their success at reproducing the coral stems from a groundbreaking discovery just a few years ago in the United Kingdom, where a then-doctorate student collaborated with Neptune Systems, a company that makes aquarium controller systems, to electronically mimic environmental settings coral rely on in the wild to spawn.

“Ever since then other institutions and other laboratories have been able to do so,” said Nicole Fogarty, the assistant professor who headed the research in the lab referred to as the Spawning and Experimentation of Anthropogenic Stressors, or SEAS facility. “This has just been a big game-changer in trying to spawn corals in technology.”

It also has the potential to help restore coral reefs that are dying off at alarming rates as a result of the changing climate, which is causing ocean warming and ocean acidification, diseases, land-based sources of pollution and habitat degradation.

An emerging illness called stony coral tissue loss disease has been spreading throughout Caribbean coral reefs.

Fogarty left Florida last year when she accepted the job as assistant professor at UNCW’s biology and marine biology department, replacing one of her former professors.

Supporter Spotlight

She has been studying coral spawning for nearly 20 years.

Stony coral tissue loss disease is the scariest threat she has seen to coral reefs in the Caribbean, she said.

“It’s devastating the Caribbean,” she said.

There are more than 800 species of coral throughout the world’s oceans. About 60 species of coral are in the Caribbean.

In 2014, the National Marine Fisheries Service listed 20 species of coral as threatened, including five in the Caribbean.

Mountainous star occurs off southern Florida to the Bahamas and may be present in Bermuda. This species of coral has in the last few decades declined rapidly and is found in the Florida Reef Tract, which is the only barrier reef ecosystem in the continental United States.

That tract has lost 90% of its mass in the last 50 years.

Reefs make up 1% of the ocean floor, but are home to 25% of marine life.

Fogarty and her team have been studying how the current threats affect the health of corals from infancy to adulthood.

Successfully spawning endangered corals may help ongoing reef restoration efforts in places like the Caribbean, Pacific and Indo-Pacific regions.

“By doing this we can then have corals spawn year-round,” Fogarty said.

The peak spawning months for corals in the Caribbean and western Atlantic region are in August and September, when the weather is warmer.

Corals reproduce only one to two times a year, after the evolution of what Fogarty describes as synchronized events.

This happens through the culmination of lunar and solar cycles, with coral usually spawning anywhere from two to 10 days after the full moon.

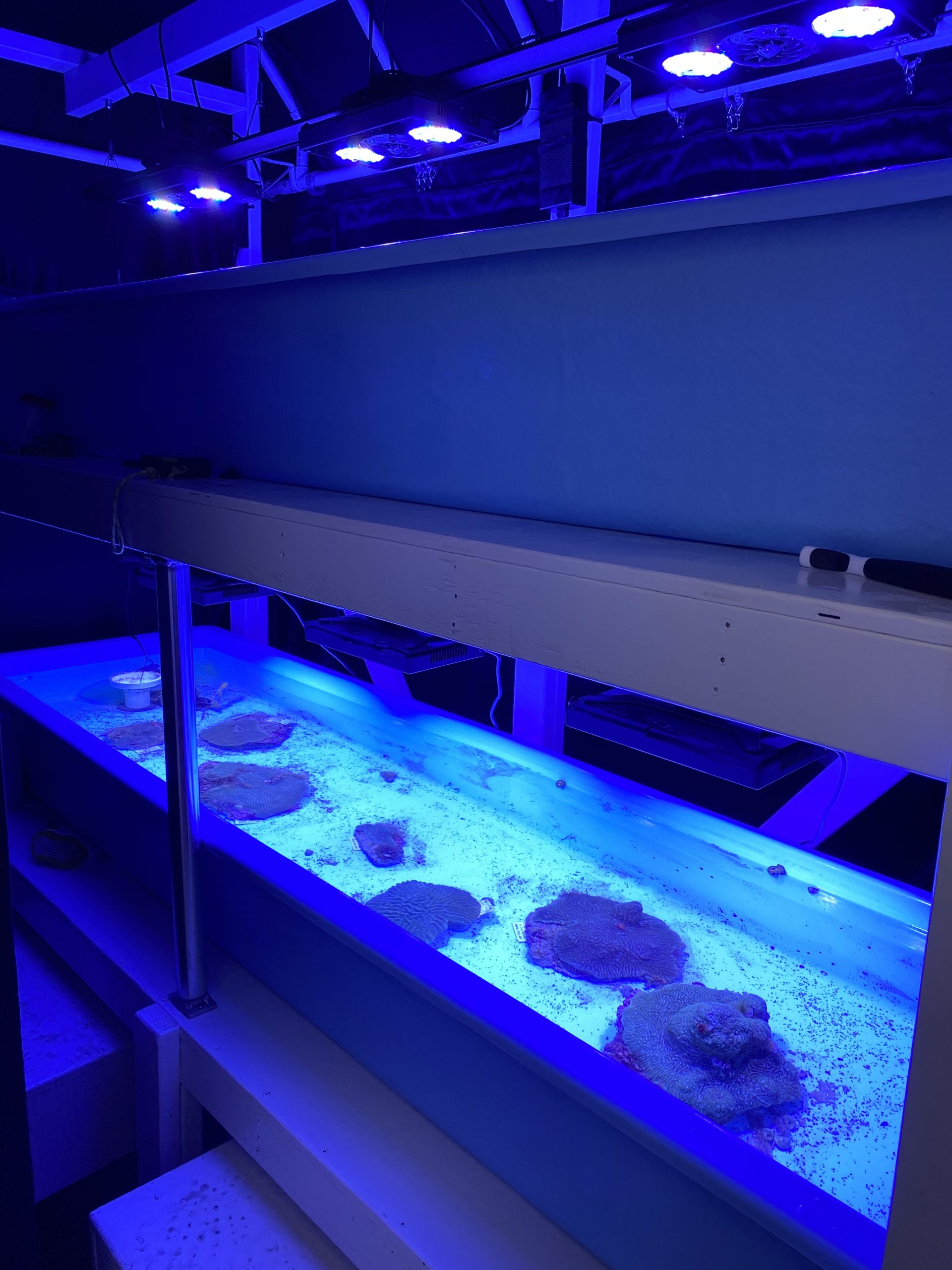

Replicating this cycle of temperature, sunlight and moonlight is key in getting coral to spawn in captivity as they would in the wild.

Setting up a system to closely mimic this cycle took time – about a year.

Research assistant Kory Enneking was instrumental in getting the computerized system – Neptune System Apex – just right to recreate the needed conditions for coral spawning in the lab.

He described the multiple parts to successful spawning. There was the upfront programming that required him to gather sea surface temperature from weather buoys off the Florida coast. He went online and pulled information about lunar and solar cycles in the Fort Lauderdale area.

Once he had that information, he keyed it into a microprocessor in what he refers to as a “set and forget” system.

Then there were the constantly changing factors, such as water quality management that had to be monitored more frequently.

The whole process took about five to six months from start to finish. It was one Enneking, who was a graduate student at the time, said is not overly complicated.

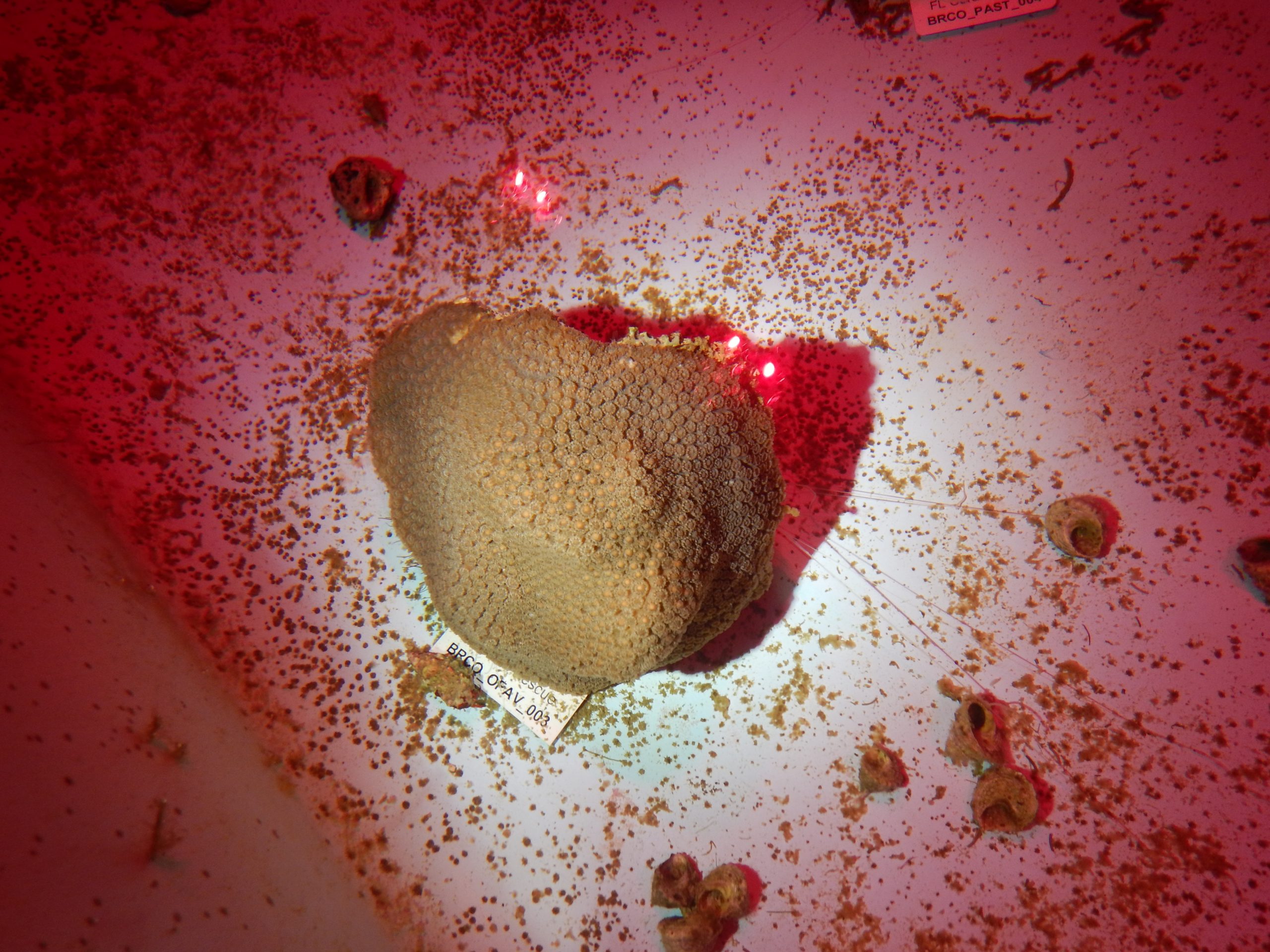

Yet, earlier this month when little pink bundles of eggs and sperm floated to the water’s surface and broke apart, thus spawning, he felt a rush of relief as he and his colleagues marveled and cheered at their success.

“It surprised me that it worked, to be honest,” Enneking said. “I’m confident in what I’m doing, but you never know until it happens. I’ve seen spawning happen probably seven, eight times in the wild through projects I’ve worked on with Dr. Fogarty. I knew it was possible. No one ever did it with the species we’ve been working on. We had some hiccups. Every project has its hiccups. Nothing’s perfect and it still worked for us. These corals are extremely sensitive and they’re hard to work with. This is potentially a solution to saving these coral reefs, give them a better chance of surviving.”

Shortly after the mountainous star coral spawned earlier this month, the lab celebrated another milestone by being the first to spawn Pseudodiploria clivosa, or knobby brain coral, in captivity.

Knobby brain coral is not a listed species. It too occurs in the Caribbean.

By being able to spawn corals year-round, the theory is that new, baby corals can be raised to a certain size where they are likely to survive when placed in a natural reef. Introducing infant coral from genetically diverse populations spawned in labs into the wild may heighten the chances of reef restoration.

“With sexual reproduction, egg and sperm are meeting and that’s how you’re getting new genetic and unique individuals,” Fogarty said. “The next big step is to get more individuals of the species.”

That will be part of the focus of their research over the course of the next year.

If they can spawn genetic individuals of the species, Fogarty said, that would be a “giant leap forward” in coral reef restoration.

Ana Yranzo, a fellow with the global conservation initiative EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered) of Existence program, works with Orbicella coral species in Morrocoy National Park in Venezuela.

She said in an email that there are currently no restoration efforts of Orbicella in Morrocoy and called the lab’s successful spawning of the coral “wonderful news.”

Some years ago, various coral species, including Orbicella annularis, from other similar reef areas were transplanted in Morrocoy, Yranzo said.

“The project was done in a small scale in one reef and other species (e.g. Meandrina meandrites, Montastrea cavernosa) were more successfully adapted than O. annularis,” she wrote. “Along the Caribbean there are have been done many (restoration) efforts, especially in fast growing species from Acropora genus (mostly Acropora cervicornis) and asexual methods have been the most commonly used, such as direct transplantation, coral gardening, and micro-fragmentation. It is important to highlight that I have never work on (restoration) and is possible that I missed some other works done on this topic. I am of course very interested in acquiring more knowledge on this subject, since it constitutes a way of contributing to the permanence of our reefs.”

Yranzo’s research has entailed assessing two types of Orbicella, including mountainous star in the national park and Cuare Wildlife Refuge, which adjoins the park and is included in the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance.

A massive mortality event in 1996 killed 90 percent of the benthic fauna in the national park, but reefs in the Cuare were not affected, she said.

“Currently, after more than twenty years of the event, the assessments done during the project (period 2018-2010), allowed us to corroborate that these species are still the main reef builders of the area, especially Orbicella faveolata,” Yranzo said. “The reefs considered the healthiest before are the same we found today and that health is related to Orbicella live cover. This includes reefs from Cuare Wildlife Refuge and from the central sector of MPA (Morrocoy National Park). So, although the reef system from Morrocoy National Park have been strongly affected by different perturbation sources, Orbicella species are still an important component. In case of Cuare Wildlife Refuge, they represent the reefs in better condition from the whole area studied.”

Just as Yrazno has been wrapping up her research project, a spill from a petrochemistry refinery near the site she has been studying occurred just days ago.

This is a terrible addition to all the stress factors that have affected the coral reef system from the area and this time we presume that reefs from Cuare Wildlife Refuge were affected because a part of the oil spot saw in satellite images were above the Refuge,” she said. “It’s a presumption because we still don’t know how reefs are after the oil spill because both MPA were closed by authorities with total access restriction. It is necessary to do an assessment of the situation to really know the impact on the different species from the fauna and flora that lives on both MPA. Not only in coral reefs, also in mangroves, seagrasses among others, all connected as an ecological unit. One of the most worried facts of these spill is that August and September are months of spawning for Orbicella species so the impact for their population could be worse.”

This story was updated Aug. 31 to include comments from Ana Yranzo.