We see the numbers every day.

New cases. Percentage of the population that’s been tested. Presumed recoveries. Hospitalizations. Deaths.

Supporter Spotlight

This is how the nation is keeping its finger on the pulse of a pandemic with no definitive end in sight.

Results of those who’ve been tested for the coronavirus, known to scientists as SARS-CoV-2, lag. Not everyone who has the virus is getting tested.

And the breakdown in which test results are reported — county-by-county and ZIP code — fail to reflect a detailed account of what the virus is doing in small cities, towns and rural communities.

What about the people out there who aren’t seeking testing because they’re not seriously ill, they’re asymptomatic, or they don’t get tested either because they do not have a medical provider or their provider does not have tests?

Research now underway in North Carolina aims to get a better overall picture of where and how the virus is being spread.

Supporter Spotlight

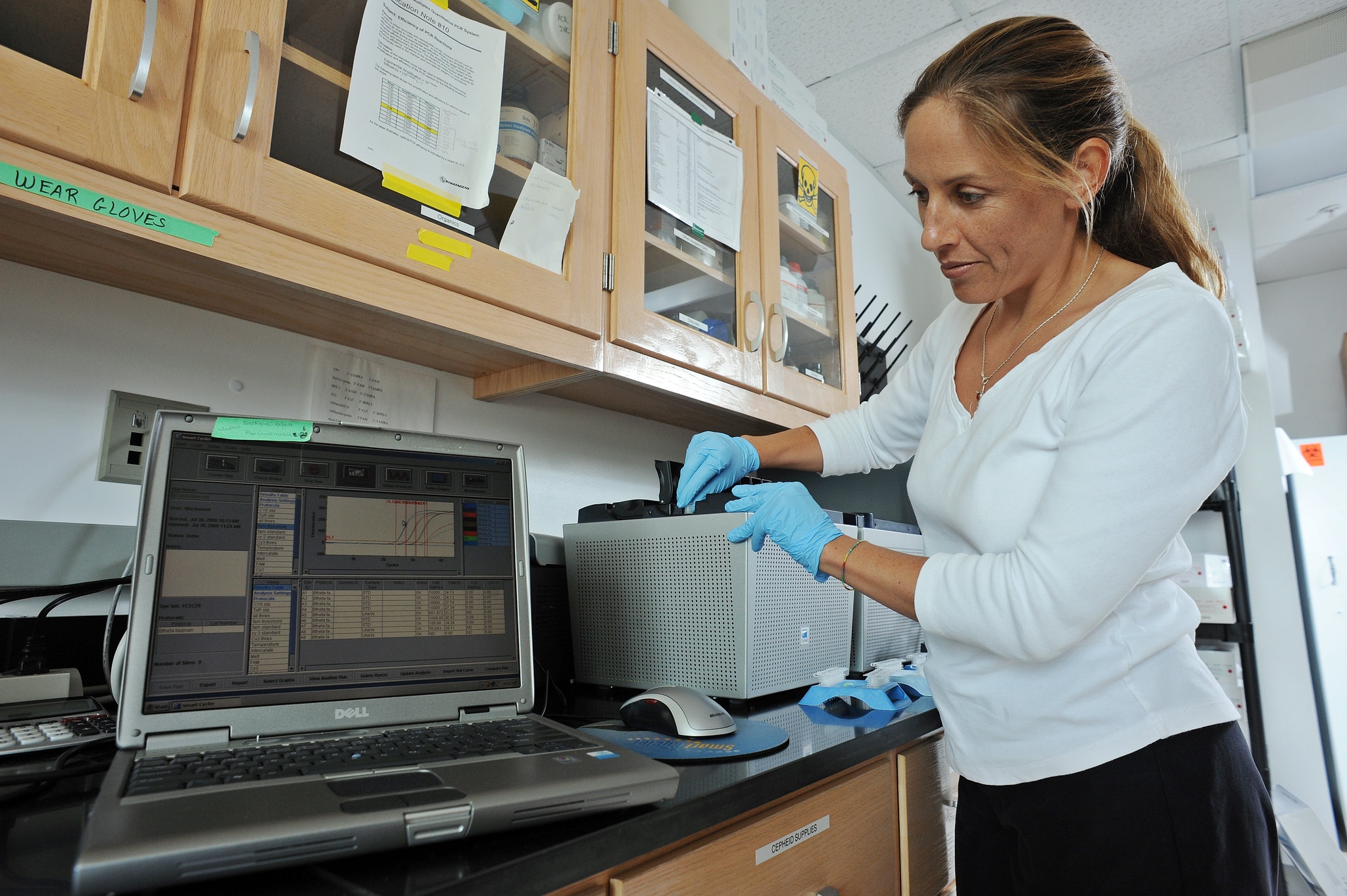

Rachel Noble, a professor of marine and environmental microbiology at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Science in Morehead City, is heading a growing team of researchers tracking COVID-19 pathogens in wastewater.

“What the research on the wastewater is intended to do is look at the amount of virus in the wastewater system knowing that when the virus gets into someone’s body, their body actually produces more of the virus, not only in their nasal passages and then their saliva, but they actually also produce more viruses throughout their gut,” Noble said. “It’s really, really important for people to realize that our research does not suggest that we get rid of clinical testing. The clinical testing is so important. What I’m saying is that there’s an opportunity for the wastewater to give us a different picture of what’s going on in the entire population because we recognize that there’s a whole portion of the population in any given town that’s being missed because they might be mildly ill or asymptomatic.”

Human waste by a sewage treatment system goes to a single location. By sampling the waste collected at these systems, whether it be a city facility or smaller collection system for say, a retirement home, researchers get access to entire populations.

Take Beaufort, for example. That coastal town’s sewage treatment plant serves about 4,000 people. Over the course of 24 hours, many people in that community will have contributed to that system by either using the toilet or taking a shower.

By taking samples from the plant over that 24-hour period, researchers will have an aggregate measure of what’s going on in that entire population.

The idea is to use this information to predict whether the number of cases may rise or level out.

“If the wastewater data is showing an upward trend then in around six or seven days the clinical cases are doing the exact same thing,” Noble said. “We’re basically getting a preview. We’re getting a little snapshot of what could come and so, if we can change some of those behaviors and learn how to use that data, then we may be able to do useful things with it.”

She explained how the information may be useful by breaking it down into three categories.

The first is the red-flag approach, where wastewater samples reveal a potential coronavirus outbreak at a facility like a nursing home or rehabilitation center.

“Just think if we would have had a wastewater monitoring approach where we see this baseline of zeroes for months and months and then, all of a sudden, you see a little blip,” Noble said. “That’s the kind of information that we would like to develop so that we can understand how that information can be used in the future.”

Wastewater research may also help us learn more about the most effective ways to slow the spread of the virus.

Imagine, Noble said, comparing wastewater systems from two rural towns.

One of the towns has extremely proactive mitigation measures — social distancing, no indoor dining, and strict measures in public spaces. The other town takes more of a basic approach to slowing the spread of the virus.

“Now you have a situation where you can actually look at the trend data for the two locations and you can begin to understand which measures might be the most effective as far as controlling the spread of the virus,” Noble said. “That, to us, is really, really important because right now if you really read of lot of what you’re seeing in the media you might notice that a lot of it is really focused on the big cities, Miami, New York City, Seattle, Los Angeles. There’s not a lot of attention being paid to these rural locations and we have a lot of them in North Carolina and we can use the data we’re seeing in different towns to try and make some comparisons and understand some of the things that work.”

Then there may be a way to use the wastewater research to help the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS, determine how people are moving around, whether it’s flocking to beaches on a Saturday or shopping.

“What if you were to use the clinical data as a backdrop, as a framework, and what if we were able to infuse both the wastewater data at the town level and the mobility data that actually tells you something about where people are going and what they’re doing,” Noble said. “Now you might be able once again to see patterns within the population.”

Her institute is part of a research team that includes the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Wilmington, University of North Carolina Charlotte and North Carolina State University in part with the state Department of Environmental Quality and DHHS.

The institute recently received $1.8 million from the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory based at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The collaboratory last month dispersed $29 million across 14 UNC system schools to fund 85 research projects focusing on treatment, testing and prevention of COVID-19.

The collaboratory in September has to update the General Assembly about the status of its research projects, which include the state’s six historically minority colleges that are researching antibodies and community testing in minority and rural populations.

One of the goals Noble hopes to achieve from the wastewater research is creating a simple system to pass along to others to collect samples, process those samples and analyze those samples.

“If we do this correctly we’re going to hand off the methods that we’re developing to the wastewater treatment plants themselves and give them the power to use these methods into the future and try to see if we can help them make this cost effective,” Noble said.

Staff at some of the wastewater treatment facilities where samples are being collected are taking those samples themselves.

Researchers, including paid university personnel as well as students, began collecting wastewater samples in late March.

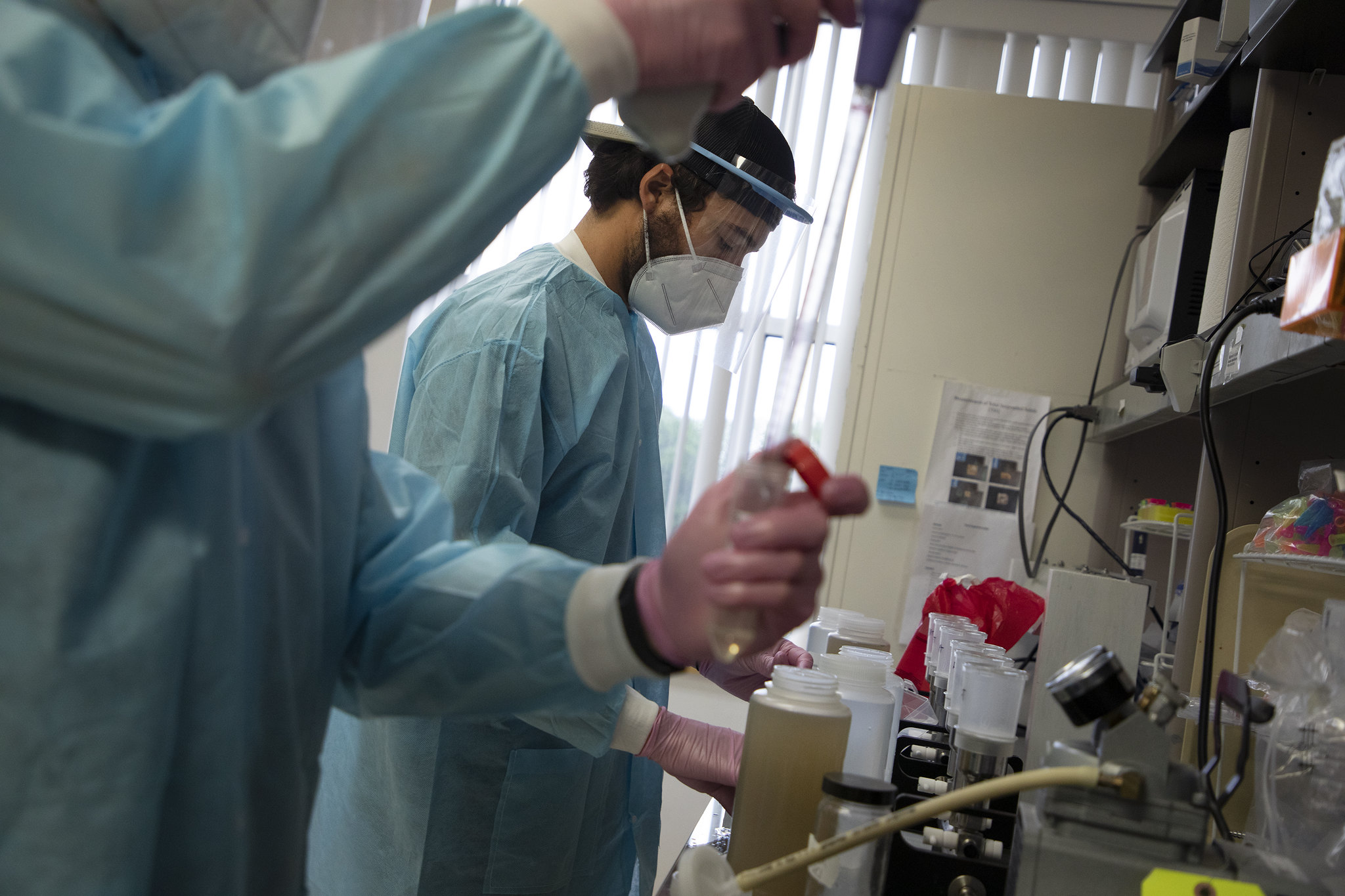

The collection method goes something like this: A 2-liter-or-so container is placed in a treatment facility’s direct flow every 15 minutes until the container is full.

The person who collects the sample is fully outfitted in personal protective equipment, or PPE.

Once the container is full, it is placed in a cooler and transferred, preferably in the back of a pickup truck, to a laboratory. The sample is then pasteurized in a hot-water bath for a period of time, which makes the virus “fall apart” to ensure it is not dangerous to the people analyzing it, but leaves enough of the virus intact to detect its presence.

“By carefully tracking every single step of that with the amount that we’ve filtered and a series of very carefully done controls when we get that concentration from the sample we’re able to work backward and we’re able to tell you what the quantity of the virus was in the initial two liters of sample that was collected,” Noble said.

At last count, the collaboratory was collecting from 18 wastewater treatment systems, including Beaufort, Newport, Morehead City, Wilmington, Charlotte, Raleigh, Durham and Cary. The collaboratory recently partnered with East Carolina University to collect and analyze samples from Greenville.

“I’m not going to pretend that we have coverage of the entire state because we don’t,” Noble said. “At the moment we’re trying to do enough work in a smattering of different locations rural, urban and in between. We’re trying to do a good job of at least capturing a wide range of systems. As we go we’ll see who we can bring on board.”

Samples are not being collected from septic systems, which, Noble points out, is an issue because more than 60% of the state’s population is served by septic systems.

“At this point in time we don’t have the resources to devote attention to septic systems, but we’re very, very interested in this question,” she said.

Still, this research will help towns like Beaufort better understand just how the virus is impacting their communities specifically, Beaufort Mayor Rett Newton said.

One of his frustrations, he said, is that Beaufort is not getting the number of active cases within the municipality.

“A couple of months ago they started releasing information about ZIP codes, but our ZIP code area is massive, so I still don’t have a clear understanding of the extend of COVID-19 in my municipality and that is deeply frustrating because I am expected to enact measures and without that data it is very difficult to know if our measures are correct or effective, and so this technology may lead us to a better understanding and maybe the best source of information absent of the data at a municipal level,” he said. “This innovative technology and process may be able to tell us the magnitude of the challenge in better scale and perhaps even well in advance of testing that comes back because there is a lag in testing. I’m just thrilled with the thought of this technology.”