As a child Janet Nye wanted to parlay her love of animals into a career as a veterinarian, but there was one problem.

She gets squeamish at the sight of blood. In particular, mammal blood.

Supporter Spotlight

So Nye who, earlier this summer stepped into the position of associate professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences, or UNC-IMS, shifted her career ambitions to another of her loves – the coast.

Every summer Nye’s family packed up to take a break from life in Charlotte to vacation at a beach, be it Nags Head, Sunset Beach or Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

Nye, 46, loved those vacations. The beach’s natural sand and saltwater playgrounds are ripe for frolicking and exploration of things living below the water’s surface.

“My parents were definitely not scientists but they certainly fostered my love of animals and science by facilitating summer marine science programs,” Nye said.

Back then, it was all about the animals and the thrill of studying them outside the confines of a classroom when she got the chance – the summer program at the University of Miami before her senior year of high school, dive classes and summer field courses in places including the Caribbean as an undergraduate student at Duke University.

Supporter Spotlight

In those early days of her higher education in the early to mid-1990s, climate change was something “far away.”

“When I was in college, climate change wasn’t a big topic of conservation,” Nye said. “There may have been one or two lectures in at least my school experience where they talked about climate change. It was definitely something that was like, that’s going to happen in the future, and a lot of people were making predictions about what might happen.”

The conversation took a turn several years later as a doctorate of philosophy student at the University of Maryland when she and other students organized a seminar on climate change. That experience “really opened my eyes to a lot of what we didn’t know” about the science behind climate change, Nye said.

The reality of climate change and its effects on the ocean’s fish that Nye was keen to study came full circle when she began her postdoctoral at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, where researchers cover 160,000 square miles of ocean from North Carolina to Maine studying fishery species and fisheries, monitoring ocean ecosystems and advise policy makers.

Nye signed up for a project that entailed her looking through 45 years of data to see whether she could see a “signal,” or long-term climate change trends.

“I didn’t think I’d see anything honestly,” Nye said. “I thought I’d see that a couple of fish species might be moving. It was quite the opposite. It was almost every fish species that we looked at had experienced a shift in geographical distribution over the past 45 years.”

“Almost every fish species that we looked at had experienced a shift in geographical distribution over the past 45 years.”

In fact, 24 out of the 36 fish stocks had some shift in distribution. Nye was shocked.

“I thought I’d see the tiniest of signals. Really, all you had to do was plot where they were and make maps of where they were over time, you could just see that where they were changed dramatically,” she said.

She shifted her research to focusing on how temperature affects fish populations and, over the last decade, has closely looked at a few species to see how they’re moving, whether climate change is causing these shifts, and gauge the impact these shifts have on the fishing industry.

For more than six years, she conducted this research as a professor at Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences in New York. She and her husband were happy in Stony Brook. But most of Nye’s family lived in the South – Charlotte, areas of South Carolina and Georgia.

Nye and her husband, a computer scientist, made an agreement: They would move their family to North Carolina if she got a job at one of the university marine labs in Morehead City.

In April 2019 she interviewed for a spot at UNC-IMS. At the time, she had already committed to do a sabbatical in Australia for about a year.

UNC offered her the job, agreeing to accommodate her schedule so she could fulfill her stint in Tasmania, an island state of Australia.

That area is experiencing some of the same shifts in distribution that researchers are seeing in the eastern Atlantic. What Nye gained most from the 10-month-or-so time she was in Tasmania was learning how to collaborate with social scientists researching how people and the coastal fishing communities in which they live and work were responding to those shifts.

She and her husband were excited about their impending move to North Carolina. Little did they know they’d be moving in the midst of a global pandemic.

They arrived in North Carolina June 8, after navigating the constraints of flying back to the United States as the case counts of COVID-19 began mounting in Southern states.

They managed the grueling, more than 14-hour flight from Qatar to Chicago with their daughter, 8, and son, 5. Being the children of scientists, they’re used to traveling.

Nye posted a “Well, it’s official” tweet July 17.

“After shifting my distribution north for a decade or more I’ve shifted back south,” she wrote. “I’ll have to migrate north occasionally for pizza and bagels, but looking forward to working with all the wonderful people in the Southeast US!”

She started July 1, a little more than a month before Carolina kicked off its fall semester. The university recently shifted to online-only courses for undergraduate students, prompted by an outbreak of COVID-19 cases among students in Chapel Hill.

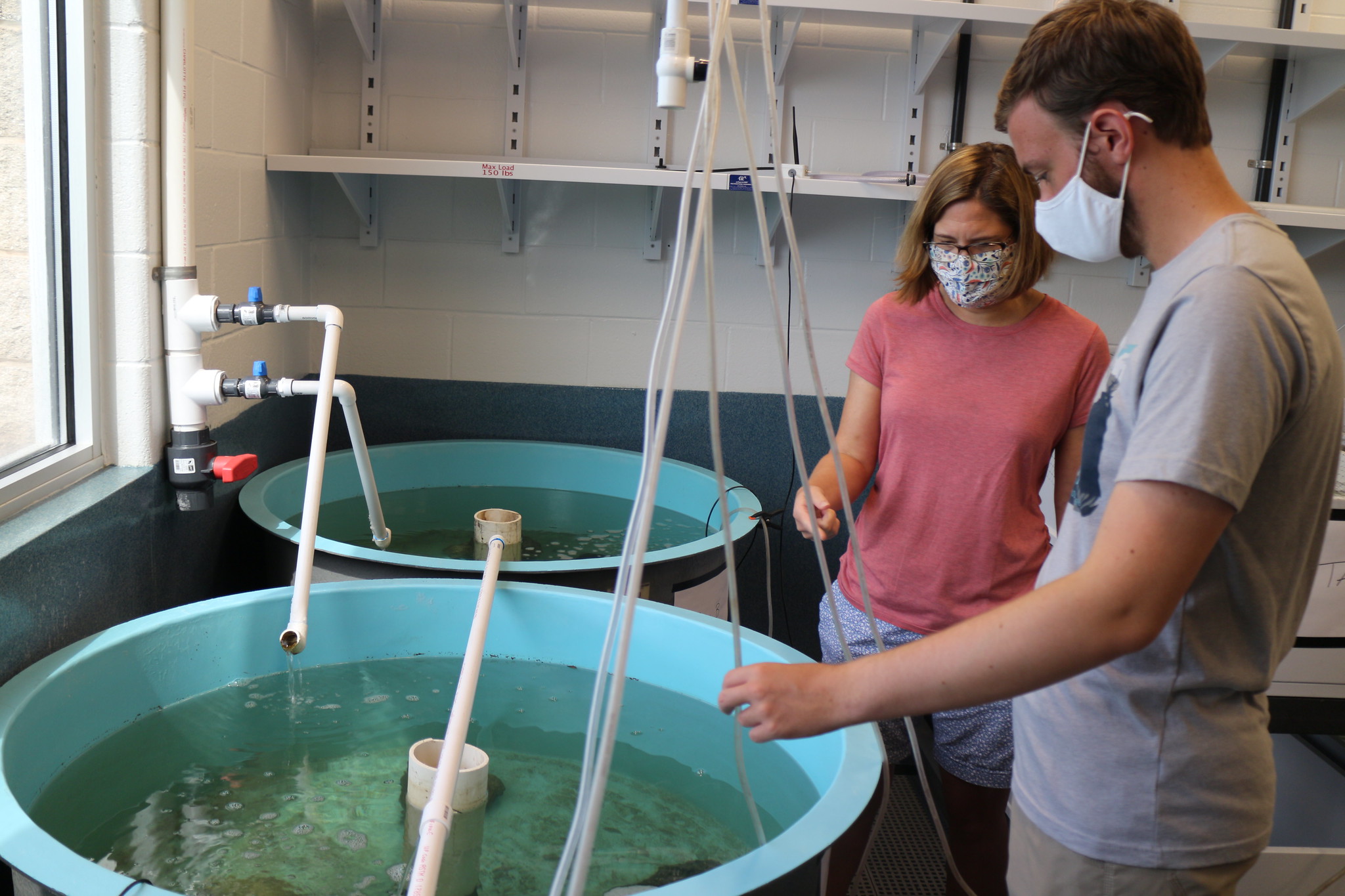

That is not the case for UNC-IMS, where the hope is to curtail an outbreak there by enforcing strict rules on how many people can be inside the building and social distancing.

“We’ve been having classes outside,” Nye said. “Who doesn’t want to have classes outside?”

She’s teaching 11 students this semester.

Her first teaching job was at a high school after she graduated from Duke in 1996. Those two years were, in her words, “probably the hardest job I ever had.”

When she decided to earn a master’s degree, she thought she would return to teaching in a high school. That changed when she realized how much she enjoyed research so she shifted her focus slightly in a way that has allowed her to both research and teach.

“Being able to guide someone through that process is really rewarding,” Nye said.

Her research is taking a local focus, studying reef-associated fish found off the North Carolina coast and whether those fish are shifting in distribution away from their reef habitat.

Nye has also become passionate about diversifying her field.

“It is really striking the lack of diversity in marine sciences and geosciences,” she said. “I think that really struck me when I became a professor. There’s a huge lack of diversity in applicants so very few African Americans and Hispanics apply to be in our marine science programs. I’m really interested in trying to understand what are the barriers. There’s no one answer.

“A lot of it is based on just really systemic racism in our culture. We’ve been talking a lot about environmentalism and how we’ve really been focusing on the animals, but we don’t often think about the people. I think marine science will be stronger when we have the voices of people of color, people from different socioeconomic backgrounds to bring different perspectives, which helps us understand the science better.”