With the Atlantic hurricane season set to begin June 1, Coastal Review Online is examining how attitudes toward climate science in eastern North Carolina have changed during the past decade. This story is the first in a special series that is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative. For more information, go to pulitzercenter.org/connected-coastlines.

Supporter Spotlight

Start a discussion of climate change, sea level rise and the associated effects with residents of the North Carolina coast and reactions and responses will be mixed, but according to polling, attitudes and perceptions here have shifted over the past 10 years.

A decade ago in North Carolina, a panel of scientists that advises the state Coastal Resources Commission released a report that found sea levels could rise up to 39 inches by 2100. The report, to be updated every five years, was intended to guide North Carolina’s planners and policy makers. The panel’s findings however, created a backlash and prompted the North Carolina General Assembly to pass a law restricting the adoption of any rule, ordinance, policy or planning guideline that defined sea level or a rate of sea-level rise in coastal counties.

“The legislature threw out our 2010 report. They said it’s not acceptable,” Stanley Riggs, a retired coastal geologist at East Carolina University and a founding member of the science panel, recalled in an interview last week.

When it came time for the panel to do its five-year update, the commission restricted the science panel in how far out its projections could go. A 30-year outlook, based on the life of a typical home mortgage, was the imposed limit. Riggs said that despite the limits, the science behind the report didn’t change.

“When we did the 2015 report, it came out exactly the same, except we knew the numbers even better, because a lot more people had been working on it. What the legislature and what the public never understood was, it was the same damn report,” Riggs said.

Supporter Spotlight

Now, as the science panel works on its 2020 report, the Coastal Resources Commission, which has new members now, has removed the previous restrictions, with 30 years now set as the minimum outlook going forward.

Christine Voss, an ecosystems ecologist and research associate at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, said the reaction to the initial report was the result of a push by real estate and other business interests to discredit the findings.

“I think that when folks felt like their livelihoods could possibly be threatened by acknowledging sea level rise and climate change, I think that there was a public effort of disinformation, quite frankly,” Voss said.

She said that the science panel’s report didn’t necessarily influence what the public thought, but the reaction to it changed the messaging, right down to materials displayed in state museums and aquariums.

“I found it very interesting that there was actually a push to administratively try to not even acknowledge what was happening,” Voss said.

Riggs compared the reaction to the report to the current coronavirus pandemic.

“This divided population, that half is willing to accept the science and believe the science and the other half doesn’t want anything to do with the science, it’s exactly the same issue because what they’re doing is projecting how this system is going to work, and people don’t want to hear that. And it’s an anti-science attitude that goes way beyond sea level rise,” Riggs said. “We’re seeing the same story play out with respect to the coronavirus, and with time, if it gets bad enough, more and more people may come around to accepting, but it doesn’t mean they’re glued to the science.”

According to scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the average global change in temperatures over land and ocean surfaces for 2019 was the second highest since recordkeeping began in 1880.

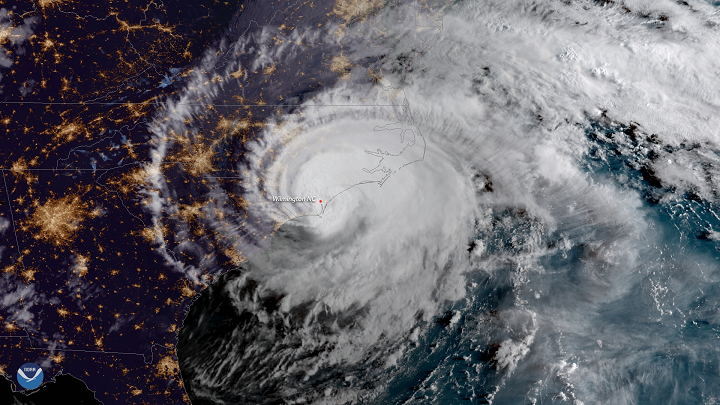

Here on the North Carolina coast, the effects are visible and often disruptive, although some residents attribute what they say they’ve seen to factors other than a changing climate influenced by human behavior. Still, the past few years, with a series of storms that include hurricanes Matthew in 2016, Florence in 2018 and Dorian in 2019, have sharpened the focus for many and possibly changed minds.

“I think that probably one of the biggest things that has changed attitudes along the North Carolina coast regarding climate change was really Hurricane Florence. I think that was a big turning point,” Voss said.

Voss, who studies the environmental changes occurring on the North Carolina coast, said it’s important to realize that for millennia, coastal areas have been dynamic places. She said signs of change such as frequent flash flooding, heavy bouts of rain and rising groundwater elevation, along with saltwater encroaching farther landward, fouling wells, killing forests and changing the landscape in other ways, are compounding with time.

Saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers, the main drinking water supply for much of eastern North Carolina, is potentially a significant result of sea level rise that’s happening now, Voss said. She said the changes are visible when using the historical images feature of Google Earth, which can delineate where saltwater intrusion has affected farm fields.

“If you go up Route 70 (near Beaufort), just south of East Carteret High School, in those areas it’s pretty darn evident,” she said. “In other areas Down East, you can see where the marsh has just kind of encroached, you can see the ghost forests. You can see where that line of trees versus marsh has changed.”

“Ghost forests,” or stands of dead trees, are clearly visible from along the Cape Fear River near Wilmington on the southern North Carolina coast up to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge on the northern coast. The refuge is a low-lying area, so the effects of sea level rise have been especially dramatic – formerly marshy areas are now open water and once-dry land is now marsh.

On North Carolina’s barrier islands, and on the mainland in coastal Carteret, Pamlico, Hyde, Dare, Currituck and Tyrrell counties, anywhere from a quarter to three-quarters of the land is at sea level, Riggs explained. Here, adaptation options are limited.

“We’re not going to engineer our way out of that,” he said. “We can’t do what the Dutch have done and build dikes around 10,000 miles of estuarine shoreline. You know, we can build it around Swan Quarter. But what do you do with Columbia, Engelhard and all the rest of the towns that are essentially 1-foot above sea level, 2 feet above sea level? They have no place to go.”

Voss said the politicization of science creates the biggest obstacle to the public’s understanding of the changes they are seeing.

“I think people are realizing that, yes, those things that we were told 30 years ago, 20 years ago that we would be seeing, we’re seeing it,” Voss said. “I think we’re gradually starting to realize that climate change isn’t something we’re thinking about as far as the future, but that the climate is changing now and we’re living in it. I think that is hard for people.”

Riggs agreed. He compared the environmental changes to what’s happening with COVID-19.

“It’s just like counting deaths right now. Now that we’ve got the 90,000 deaths in this country, people are starting to realize that something’s really going on,” he said.

But understanding is not the same as dealing with the fundamental, long-term problem, Riggs said.

The state’s worst natural disaster

Hurricane Florence, a deadly Category 1 storm that made landfall near Wrightsville Beach early in the morning of Sept. 14, 2018, was the state’s worst natural disaster, totaling somewhere around $22 billion in property damage. Rainfall and flooding levels across eastern North Carolina were unprecedented because of the slow-moving storm, and not just on the immediate coast.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, a state record rainfall total of 35.93 inches was set in Elizabethtown in Bladen County, breaking the previous record for rainfall from a tropical system of 24.06 inches, a four-day deluge measured during Hurricane Floyd in 1999 in Southport, in coastal Brunswick County. Florence followed another record-breaking storm: Hurricane Matthew in 2016 also made landfall in southeastern North Carolina as a Category 1 storm, was blamed for 25 deaths in North Carolina and caused catastrophic flooding across the coastal and central parts of the state.

USGS hydrologist Toby Feaster said in December 2018 that record flooding during Florence was measured by stream gauges in the state that had decades of data. Feaster led a study that showed 45 stream gauges in North Carolina and four in South Carolina recorded flows that ranked among the top five on record. There was more than 70 years of historical data at some sites with record-breaking flooding. Peak stream levels at nine locations indicated that Florence was a greater than a 500-year flood event.

“Since several of the (sites) we analyzed had more than 30 years of historical data associated with them, it was interesting that a majority of the number one and two records were from back-to-back flooding events,” Feaster said at the time, referring to Matthew and Florence.

For many along the North Carolina coast, the hurricanes of the past few years were the first natural disasters they had experienced. This is especially true for young people, including Daniel Van Skiver of Brunswick County on North Carolina’s southern coast. Van Skiver is one of several Brunswick Early College High School students who submitted essays on their experiences for this series.

“Florence left me in a state of helplessness and, being one of the many people in Brunswick County with financial problems, there was no way out,” Van Skiver writes. “My home was left in an almost unlivable state, my bed was soaked through from a hole in my bedroom roof, and the problem did not stop witha the passing of the hurricane. The water damage brought infestations of bugs and rotted away other parts of the house that had been untouched. If I had not been able to stay with my brother, I would have most likely been out on the streets, a living arrangement that would last the next seven months as me and my dad looked for a house.”

Lindsey Clark, another student at the Brunswick County school, also writes of her family’s experience with Florence, which flooded her home.

“It has almost been a year and a half since it has happened and we still feel the effects of it today,” Clark writes. “It hurt each part of the family differently and was so heartbreaking. We lost all of our old family photos, clothes and our home. It was difficult to build back up again and to try to get back on our feet. We felt stuck and felt like we had nowhere to go and did not know where to turn. You really do not realize how much you have until it is taken away from you.”

Not only young people, others in coastal communities are seeing unprecedented floods during storms.

In a recently compiled series of recordings by the Duke University Marine Laboratory in Beaufort and the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center on Harkers Island, a partner with Coastal Review Online in this reporting project, Louie Piner of the unincorporated Carteret County community of Davis said Florence was unlike any storm he’d seen. Folks in the low-lying Down East part of the coastal county are accustomed to weathering storms.

“Well, I’ve been through quite a few hurricanes. I’ve lived in Davis all my life. And we’ve had quite a few. But Florence is the only one that the house I live in has ever had water in it. The house was built in 1946. And we’ve seen a lot of storms, but it has never had water in it until hurricane Florence,” Piner said.

A poll conducted by Elon University in October 2018 sought to gauge how Hurricane Florence affected North Carolina voters and how they viewed threats to coastal communities and policy questions related to climate change. The poll found that opinions had shifted since the university conducted a similar poll in 2017. The poll found that 51.5% of North Carolinians believed that climate change is very likely to have negative effects on coastal communities, with 31% saying it is somewhat likely.

That’s compared to 45% who said the negative impacts were very likely and 28% who said they were somewhat likely in the 2017 poll. Pollsters said the shift appeared to be driven by attitude changes held by Republican voters.

The 2018 poll also found that nearly 54% believed hurricanes were becoming more severe and that 62% believed that climate science should be incorporated into local government planning and ordinances.

A year later, Dorian

Almost exactly a year after Hurricane Florence, another Category 1 hurricane made landfall on the North Carolina coast. Again, the wind-speed category was no indication of the damage to come.

Hurricane Dorian flooded the village on Ocracoke Island Sept. 6, 2019, ultimately resulting in the destruction of 47 structures, county officials said earlier this month. The number caught even villagers by surprise, Peter Vankevich, copublisher of the Ocracoke Observer, another partner in this series, said recently.

“The Ocracoke Preservation Society’s museum next to the big (National Park Service) parking lot had never been flooded,” Vankevich noted in October 2019. “’If that building ever gets flooded, this island will be in big trouble,’ someone once remarked.”

The museum suffered extensive flood damage with 5 inches of water inside.

About 400 of the island’s roughly 1,000 residents were displaced and nearly every structure on the island was damaged when the storm surge reached 7.4 feet at 8:30 a.m. Sept. 6, 2019. Ocracoke’s storm surge during Hurricane Matthew was 4.7 feet.

Mike Riccitiello, a structure specialist with the North Carolina Emergency Task Force, was part of six crews on the island after the storm to document structural damage, Connie Leinbach, the other co-publisher of the Ocracoke Observer reported.

“One gentleman I talked to has lived on the island 65 years and said he’d never seen storm surge this bad,” Riccitiello said at the time.

Jade Lopez is a co-owner of Taqueria Suazos on Ocracoke Island. She said that when Dorian came through, her family had to be rescued.

Doug Eifert, co-owner of Dajio Restaurant, on Ocracoke Island also suffered significant damage at his business. He said nobody expected the storm to be so bad.

Charles Temple, an English teacher at Ocracoke School, described Hurricane Matthew as the worst storm to hit Ocracoke since the 1944 Great Atlantic hurricane, and Dorian’s floodwaters in the village reached 18 inches higher. He called the storm’s devastation “a gut shot.”

Despite the extensive damage, federal officials determined that villagers didn’t qualify for individual assistance, the form of disaster aid that provides financial help and services for people to do home repairs and cover costs of temporary housing, clothing and medical needs.

Ocracoke’s economy is tourism. Its restaurants, small shops and accommodations largely remain closed since Dorian. The storm’s damage led officials to keep the island closed to all but residents for more than two months after the storm. Now, the COVID-19 pandemic has compounded villagers’ troubles as they try to rebuild and recover from Dorian.

For those who can reopen, many are apprehensive, and some are choosing to remain closed as summer vacation season begins, Vankevich said.

“First of all, people are going to be coming to a different Ocracoke,” Vankevich said, adding that the many businesses wouldn’t be open, either because of concerns about the coronavirus or because they were damaged or destroyed by Dorian.

“All these kind of wonderful landmarks that have people coming here are not going to be there,” Vankevich said.

Jennifer Allen and Dylan Ray contributed to this report.

Next in the series: Communicating, understanding and responding