American shad are found along the entire East Coast, ranging from the St. Johns River in Florida to Labrador.

On the West Coast, American shad are considered an exotic species, having been introduced at the end of the 19th century. They are now found from Sacramento, California, to southern Alaska.

Supporter Spotlight

According to the American Shad Habitat Plan published in 2014 by the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, American shad return to all coastal rivers in North Carolina each spring, and are most abundant in the Roanoke, Chowan, Tar/Pamlico, Neuse, Northeast Cape Fear and Cape Fear rivers, as well as in the Albermarle and Pamlico sounds.

In North Carolina, American shad are also referred to as white shad.

According to a report by Keith Ashley and Kevin Dockendorf, fishery biologists with Wildlife Resources, American shad historically supported important, and sport and commercial fisheries along the Atlantic coast. Overfishing, pollution and the construction of dams, which block migrating fish from reaching spawning grounds, nearly wiped out many shad runs along the coast.

Construction of hydroelectric dams across major river systems, overfishing and water pollution from increased development led to degraded spawning habitat across the state. This in turn led to a decrease in the reproduction and numbers of American shad in North Carolina waters.

Currently, the federal and state resource agencies are working to restore American shad to many North Carolina Rivers throughout the state.

Supporter Spotlight

American shad populations declined sharply in the late 20th century, however, this trend may be reversing, thanks to the cooperative efforts of Wildlife Resources and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Since 1998, the two agencies have worked together to restore depleted populations of American shad along the Atlantic coast by stocking more than 8 million “marked” shad fry in the Roanoke River as part of the Roanoke River American Shad Restoration Program, said Ashley and Dockendorf.

The Roanoke River restoration effort includes moving spawning adult shad upstream of major dams on that drainage and stocking hatchery-reared American shad fry. At the same time dams are being removed, fish passages are being built to allow free, unencumbered upstream access to historic spawning grounds and safer downstream passage for adult and juvenile shad heading back out to the sea.

The recreational sport fishery is more important to North Carolina residents than commercial fishing for this species in rivers still with viable spawning populations, including the Cape Fear, Neuse and Tar and Pamlico rivers.

As an example of the importance of this species to the region, the Grifton Shad Festival, beginning in 1971, is one of the longest-running festivals in North Carolina. It is the oldest festival in Pitt County and the second oldest in eastern North Carolina. Or, as billed on the town’s website, it’s “One of the oldest and most Shadtastic Festivals in all of North Carolina.”

Grifton has been recognized by the North Carolina General Assembly as the official shad capital of North Carolina.

But because of the coronavirus pandemic, the festival is on hold. A date for the event is to be announced, festival organizers announced March 20.

Frequently misidentified

American shad are frequently confused with hickory shad because they are similar in size and both have four to six dark spots along both sides of their bodies. The lower jaw of the hickory shad sticks out beyond the upper jaw, where the American shad has both the upper and lower jaws being of the same length. Both species will school together and share the same habitat.

During the spawning run, typically from late February through early April in North Carolina, adult American shad do not feed, but will strike at artificial lures, including darts and small shiny spoons.

American shad are said to give a better fight than hickory shad, but they do not “leap” out of the water like the hickory shad once hooked.

Shad are anadromous fish, feeding in the open ocean until maturity, and then returning to freshwater rivers to reproduce. The American shad is also a migratory species, moving generally north during the spring and summer, and south during the fall and winter. Some shad travel over two thousand miles in a single year.

A small group of shad winter off the coast of Nova Scotia, moving into the Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of St. Lawrence and along the coast of Labrador to spawn in summertime. As summer approaches, adult shad from all along the East Coast gather in the Gulf of Maine. Large numbers move into the Bay of Fundy, following the coast of Nova Scotia in late spring, and move through the head of the bay through the summer months. As summer turns to fall, the shad move along the coast of New Brunswick as they begin the return trip south. They continue to travel south through the fall. Most spend the winter months feeding in the waters off the mid-Atlantic states.

Shad born in Southern rivers continue on, arriving in Florida and Georgia in time to spawn in January and February. In the spring, the spawning run moves steadily up the coast: the Carolina’s in March, April in Chesapeake Bay and May and June in the northeast. The northerly migration pattern of American shad varies with the age of individual fish. Mature adults returning to spawn travel faster and closer to shore, while the juveniles travel more slowly and farther offshore and continue to feed at sea.

Spawning adults locate their home region by orienting themselves to ocean currents and changes in water salinity. The exact method by which shad identify their specific home stream is still largely unknown. Research has suggested that the principal homing mechanism may be olfactory in nature. Shad may find their natal stream by recognizing its unique smell.

Shad returning to spawn gather in the estuary of the mouth of their home river, waiting for the right conditions. Water temperature is the key factor in determining when shad will make the upstream run. Upstream movement and spawning begin when the water temperature has reached about 54 degrees Fahrenheit and continues until the temperature climbs to 68 degrees, with peak activity occurring at about 65 degrees. Although temperature is the main trigger, water volume flow, water clarity and the lengthening period of daylight are also factors that affect the timing of the spawning run.

Shad spawn in the main stem of rivers, in areas of moderate current flow. Spawning occurs at night, beginning at sunset and continuing until about midnight. Most likely, some form of chase is involved, with males swimming in tight circles around the females.

Females release their eggs directly into open water as shallow as 3 feet, or as deep as 20 feet. Males swimming nearby release milt to fertilize the eggs as they slowly sink. After spawning, shad that have survived the difficult upstream journey and the exhausting process of spawning return downstream almost immediately to rejoin the offshore juveniles as they begin their springtime migration through the Gulf of Maine.

The number of eggs a female American shad will release depends on the latitude of the river of origin. Southern shad may release over a half million eggs but will only live to spawn once. Shad on the northern end of the range will release only 100,000 to 200,000 eggs, but may return to spawn more than once. The average spawning release for the female along the mid-Atlantic coast is between 200,000 to 400,000 eggs.

Large numbers of eggs are needed to offset intense predation. Predatory fish, such as bass and pickerel, and birds, such as gulls and cormorants, eat both eggs and juvenile shad. Offshore, striped bass, porpoises and sharks are among the many predators that feed on shad. Only one out of every 100,000 fertilized eggs will develop into a fish that survives long enough to return to spawn as an adult.

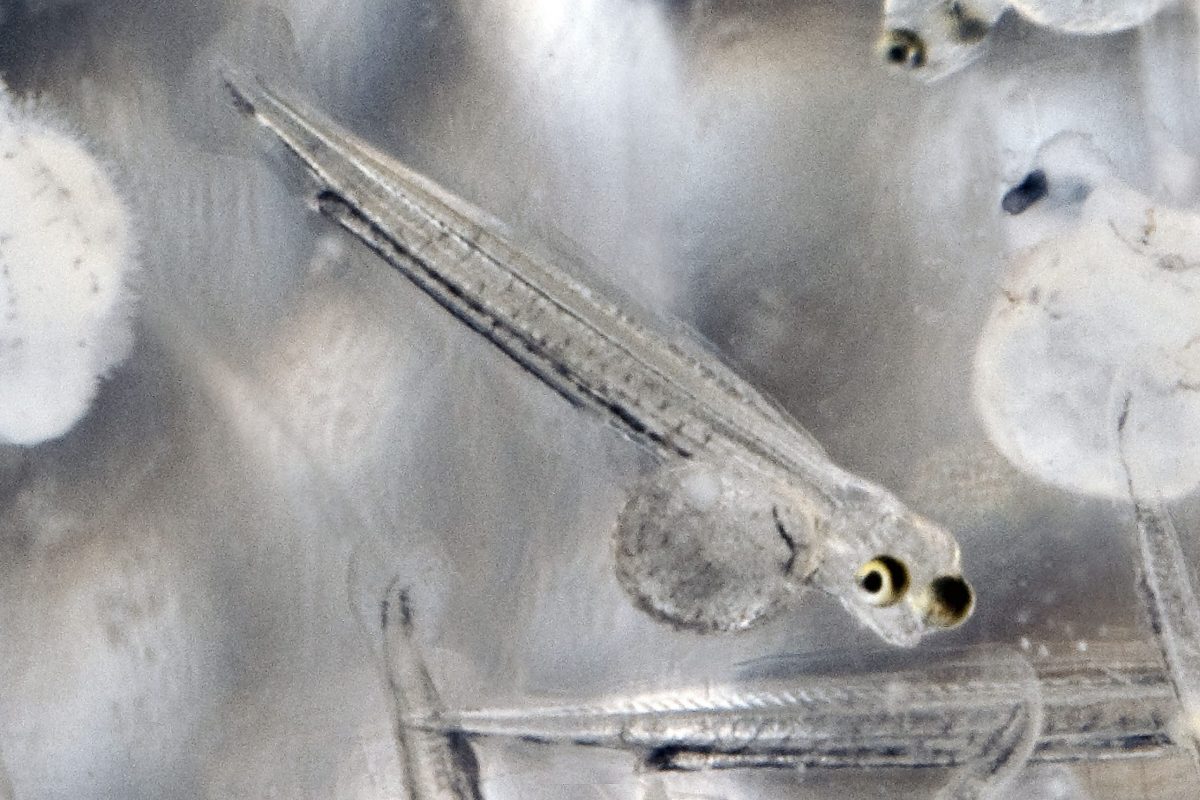

After fertilization, the newly laid eggs are carried downstream by the current and hatch in six to 12 days, depending on water temperature. The eggs hatch to release a transparent, thread-like larvae which is slightly less than 1/2 inch long. Larvae feed on microscopic plankton in the surrounding water. The millions of newly hatched shad larvae are also an important part of the rich mix of plankton found in rivers and estuaries, providing a significant food source for other species in the food chain.

When the larvae are about 4 to 6 weeks old, they start to develop into the juvenile stage and begin to more closely resemble adult shad. Juvenile shad spend the remaining weeks of summer moving constantly, feeding throughout the water column. By summer’s end, the juvenile shad have grown to be about 3 to 4 inches in length. As water temperatures begin to drop with the approach of autumn, the young shad begin to move downstream and out into the ocean, where they spend the next several years feeding and growing. They remain in the open sea until they become sexually mature at 3 to 5 years for males, and 4 to 6 years for females.