In April, Dr. Anthony Fauci, a key member of the national COVID-19 task force, called out shaking hands as a particularly dangerous custom that should be relegated to the past.

“ I don’t think we should ever shake hands ever again, to be honest with you,” he said in a Wall Street Journal podcast. “Not only would it be good to prevent coronavirus disease — it probably would decrease instances of influenza dramatically in this country.”

Supporter Spotlight

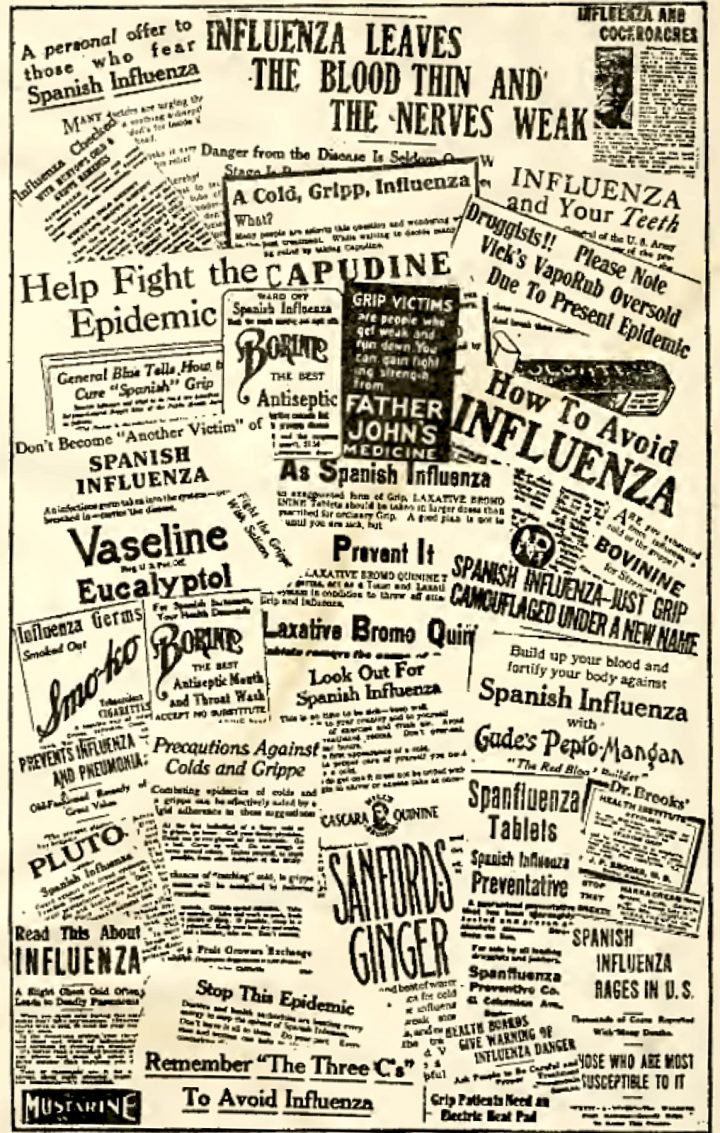

It was not the first time in our nation’s history that the custom had been called into question.

“Let’s quit shaking hands. It is a filthy and abominable habit from the barbaric past … Having served its day and purposes it ought to relegated to oblivion,” W.O. Saunders, the publisher of the Elizabeth City Independent, wrote on Feb. 7, 1919.

Fauci’s plea is in response to the COVID-19 virus; Saunders was writing at a time of the deadliest pandemic the world had ever seen — the Spanish flu.

The trenches of World War I may have been the perfect petri dish for the disease.

“The war fostered influenza in the crowded conditions of military camps in the United States and in the trenches of the Western Front in Europe … at the height of the American military involvement in the war, September through November 1918, influenza and pneumonia sickened 20% to 40% of U.S. Army and Navy personnel,” Dr. Carol Byerly wrote in The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919. The article, published in 2010, was written for the National Institute of Health.

Supporter Spotlight

But in the horrors of the war, there was little notice taken of a flu-like illness that seemed just one of many ways to die. And if notice was taken, no one wanted to let the enemy know the ranks of its soldiers were being thinned by disease.

It became known as the Spanish flu because the press in Spain, which was neutral in the war, could report on it in its uncensored newspapers. The disease spread rapidly across the globe, reaching its peak in 1918-1919, although there is some evidence that it continued into 1920. When the final tally was taken, the H1N1 strain of the flu virus had infected 500 million people and killed an estimated 20 million, although most experts feel that figure is low.

The first cases of a new virulent influenza-like disease may have occurred in January and February 1918 in Haskell County, Kansas. The county’s physician, Dr. Loring Miner, was so concerned about what he was seeing that he alerted the Public Health Service, the predecessor to the National Institutes of Health, according to John Barry the 2004 article “The Site of Origin of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Its Public Health Implications.”

“Miner considered this incarnation of the disease so dangerous that he warned national public health officials about it. Public Health Reports (now Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report), a weekly journal produced by the U.S. Public Health Service to alert health officials to outbreaks of communicable diseases throughout the world, published his warning,” he wrote.

By March of that year the first cases had appeared at Fort Funston, Kansas. Although Haskell County was 300 miles to the west, Fort Funston was where new recruits were sent to be trained for the trenches of World War I.

Although the Spanish flu was an influenza virus, it was novel, unlike any that had been encountered.

Flu viruses in the past had attacked the youngest and the oldest — the immature and weakened immune systems. But this new version of the virus assailed the young and healthy, attacking the lungs and filling them with fluid and often causing death within 48 hours. The blue death, it was sometimes called, as damaged lungs tried in vain to supply oxygen to the victim’s blood.

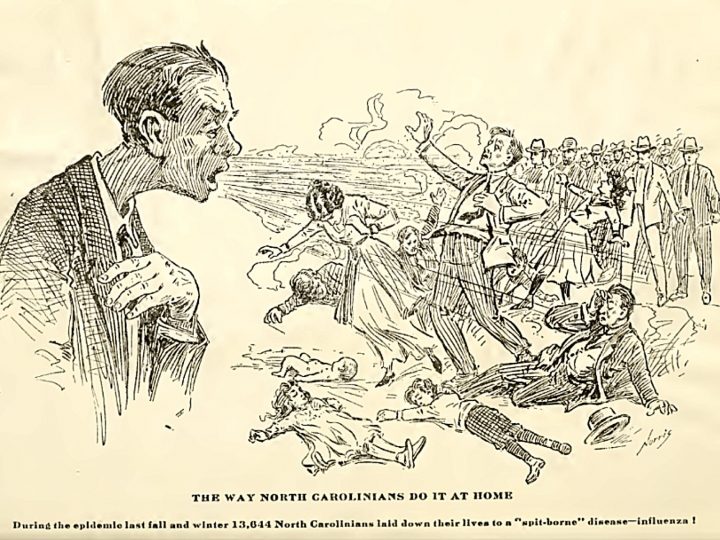

The official death toll from the Spanish flu in North Carolina was around 13,700. Relative to today’s population, that would be about 56,000 fatalities.

The first case in the state was recorded Sept. 19 in Wilmington. In two days, William Wright, 29, was dead, according to the Wilmington Star-News. Within a week the city reported more than 500 cases.

At the time, Wilmington was home to a state-of-the-art medical facility, the James Walker Memorial Hospital, but it was quickly overwhelmed by the patients who were streaming in.

The virus spread swiftly, taking advantage of the state’s transportation system.

“The virus moved westward, along railroad lines,” David Cockrell wrote in “A Blessing in Disguise.”

In Raleigh, 288 people perished by the end of October.

Then-Gov. Thomas Bickett quickly realized the enormity of what was confronting the state. On Oct. 3 he released a 600-word statement to the press that included a brief history of the disease.

“The disease started in Spain in May, this year, involving 30 percent of the population of that country within a short time. Already the disease has invaded and practically passed through Europe …” he wrote.

The governor noted that the disease was transmitted through “spit swapping,” which included “coughing or sneezing into the air instead of a handkerchief… ; soiling the hands with spit … and using common drinking dippers.”

Finally, acknowledging that there was no treatment, he ended with, “In conclusion, public officials can do little to protect you. You can do a great deal to protect yourself.”

In his message, Bickett encouraged the public to stay home, to not congregate. The governor seemed to be ahead of his own health department and the federal government, according to Laura Austin in her 2018 University of North Carolina Charlotte public policy doctoral thesis, “Afraid to Breathe.”

“Despite the fact that the day before, Oct. 2, The News and Observer reported that neither the state nor the national health authorities considered quarantine measures practicable, the governor was encouraging people to stay at home in hopes of decreasing the circulation of the disease,” she wrote.

Bickett tried another tactic, reissuing the information he sent to the papers though the North Carolina Council of Defense, a statewide organization administered within each county that was created to support the war effort during the war.

That message got through to county officials, Austin noted, although each county decided for itself what measures to put into place.

“When Governor Bickett issued requests to the councils of defense in each county by telegram in early October 1918, the response was immediate,” she wrote.

In New Bern, Craven County, when a case of Spanish flu was diagnosed, the house was quarantined. Dorcas Elizabeth Carter , who died in 2009, was 4 in 1918 when her African American family became ill. Eight-five years later, in a 1999 interview she still recalled what it was like. The virus didn’t recognize racial boundaries, but society did at the time, as her memories make clear.

“All of my family, there were six of us, had influenza. We had a black doctor. Dr. Fisher. There were six of us in one room. Coughing, Lord I thought we were going to die. He had a black nurse to go to all of us. Because all of the homes there were quarantined. A mother and child across the street from us died of it. And down the street another person.”

Cities were where the death toll was highest, but rural counties were also affected. Roy Sawyer’s article for the Tyrrell County Genealogical and Historical Society, “The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Life on the Alligator River,” examined the effects of the disease on Tyrrell County.

Columbia, the county seat, was a relatively thriving town on the Scuppernong River with a population a little more than 2,000 in 1918.

The first flu death in town was 14-month-old Samuel Baty on Oct. 14. More deaths followed, Sawyer writes, quoting Blanche Cohoon as saying the situation was, “the most dire situation” of her life.

“Folks were dropping dead throughout the county,” Cohoon said. “It was almost an hourly message that some friend had died.”

Columbia had two physicians in town, but there was still no treatment for the disease. The state has been estimated to have had a 20-25% infection rate. In the four months that the flu ravaged the town, the infection rate was 35%. Flu was the official cause of death listed for 18 residents.

But if Columbia and Tyrrell counties had doctors available to treat the sick, not every place did. And when doctors were flown in to treat Coast Guardsmen and others on the Outer Banks, not everyone here appreciated the kind of attention the newfangled aircraft attracted.

“Flying Machine Advertises Flu” the headline read on the front page of the Elizabeth City Independent Jan. 31, 1919. “Dare County Folk Don’t Like Publicity of Flu Fliers” was the subhead.

“Fighting the Flu via aero may be great sport for the U. S. Medical Corps and furnishes interesting headlines for newspapers but it isn’t making the strongest sort of appeal to the people of Dare county who are the beneficiaries (or the victims) of this latest adventure,” the article explained.

But Dare County was suffering from the flu epidemic like every other North Carolina county.

“B. G. Crisp, an enterprising lawyer of Manteo,” had conceived the idea of getting aid from the U.S. Public Health Service on the ground that influenza had broken out in Coast Guard stations, “of which there are a great number in Dare County.”

The Health Service stayed a week and declared “local physicians had the situation well in hand.”

It would seem, though, that they never got to Hatteras Island.

Navy Chief Pharmacist’s Mate George McNabb was sent to Hatteras Island in 1918. In 1926 he wrote “Reminiscences of an Influenza Epidemic” for the Navy Hospital Corps.

“In 1918 an epidemic of Spanish influenza was rampant in the area of Cape Hatteras, N.C. Under instructions issued to me I was to proceed to that vicinity and render treatment to the afflicted to the best of my ability. My medical outfit consisted of a 4-ounce bottle of tincture of iodine, 1 clinical thermometer, 1 pound of magnesium sulphate, and 100 vegetable-compound pills. A few days later the medical supplies were increased by one standard torpedo-boat medical box,” he wrote.

He spent two years trekking up and down the island, often with a Coast Guardsman at his side, his effort evidently successful.

“Only one death occurred out of over 500 cases treated,” he reported.

“It was with great reluctance that the writer left these good people, for, after having spent 2 years among them, he felt that he had become one of their own,” McNabb wrote of his time on the island.