In the first of his series recognizing February as Black History Month, historian David Cecelski explores the roles two of eastern North Carolina’s black leaders played in the civil rights movement. Read more of Cecelski’s series at davidcecelski.com.

I love this billboard on the site of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. I saw it a few years ago, just before the museum opened, and I immediately lit up because it was so nice to see the faces of two extraordinary people from the North Carolina coast in such a place of prominence in the nation’s capital.

Supporter Spotlight

I recognized them immediately: Jacquelyn Bond, a 15-year-old civil rights activist from Williamston, and Golden Frinks, a legendary civil rights leader from Edenton, and a compatriot of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In the photograph, they are singing at the famous March on Washington where Dr. King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech Aug. 28, 1963.

The photograph of the two civil rights activists is one of many treasures at the National Museum of African American History and Culture that speak to the history of the North Carolina coast.

I’m back in Washington, D.C., and the museum is now open so I can explore its collections that shed light on North Carolina’s coastal history.

As my way of celebrating Black History Month, I’m going to feature stories about that photograph and eight other artifacts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Supporter Spotlight

I’ll start with that photograph of Jacquelyn Bond and Golden Frinks.

Then, over the next few weeks, I’ll look at some of the museum’s other artifacts related to the history of the North Carolina coast. They’ll include another couple photographs, a postcard, a pin, an old book, a couple of famous lunch counter stools, a painting and a silk linen shawl worn by one of the most important freedom fighters in American history.

So let’s get started and explore the story behind our first photograph, the one of Jacquelyn Bond and Golden Frinks at the March on Washington in 1963.

The Williamston Freedom Movement

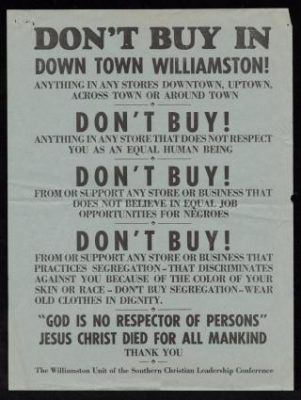

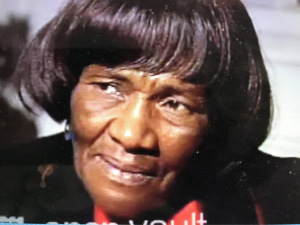

When the photograph was taken, Jacquelyn Bond, later Jacquelyn Bond Shropshire, was only 15 years old. Her hometown, Williamston, was in the throes of a long civil rights struggle that would later be remembered as the Williamston Freedom Movement.

Bond later said that she first heard about the March on Washington while she was in jail in Williamston. She had been arrested for nonviolent civil disobedience when she protested Jim Crow racial segregation by using a “whites only” coin laundromat.

She had a reputation for fearlessness. She walked in the front of protest marches. She did not stop when she saw Klansmen.

When her teachers tried to stop her from joining a protest, she left school and just kept going.

During a civil rights protest earlier in 1963, a deputy sheriff had hit Bond in the stomach with an electric cattle prod. She bore the scar for the rest of her life, but she was undaunted.

That summer of 1963 Bond and other schoolchildren in Williamston stood up to drive-by shootings, Ku Klux Klan attacks and police brutality, including the electric cattle prod that struck Bond.

The young people were unrelenting. As soon as Bond was out of jail, she talked her father, a local grocer, into sponsoring one of three buses that carried Williamston civil rights activists to the March on Washington.

At the March on Washington, Bond, Golden Frinks and those three busloads of mostly black students were among the 250,000 people that witnessed Dr. King deliver his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Golden Frinks also played a central role in the Williamston Freedom Movement.

Frinks worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the national civil rights group that Dr. King, Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin and other black leaders founded in 1957.

Dr. King asked him to work with the SCLC after Frinks led successful civil rights protests in Edenton, his hometown, in 1960-1962.

As SCLC’s regional field secretary, Frinks seemed to be everywhere in eastern North Carolina in the 1960s and early 1970s.

I can’t even begin to list all of the towns where Frinks played a central role in local civil rights movements: right off the top of my head, in addition to the Edenton Movement ,I can think of Elizabeth City, Plymouth, Washington, Windsor, Bethel, Greenville, Ayden, Robersonville and of course Williamston, just to name a few.

There were 800 arrests of civil rights protestors just in Ayden, a town of only 3,800 people in Pitt County, and it was one of the smaller local movements with which Frinks was involved.

Frinks also played a key role in the Hyde County school boycott in 1968-69, the subject of my first book, Along Freedom Road.

During those civil rights struggles, Frinks was attacked and beaten many times. He saw thousands of protestors go to jail for nonviolent civil disobedience, and he went to jail himself more than 80 times.

He had gotten to know Jacquelyn and the rest of the Bond family during the Williamston Freedom Movement. Earlier that summer of 1963, Frinks and Sarah Small, the president of the local SCLC chapter, had led protest marches in the small town for 32 consecutive days.

Jacquelyn Bond and other young people were at the forefront of those protests.

In our photograph, she and Frinks are singing one of the Freedom Songs that the young activists sang to keep up their spirits during the civil rights protests back home in Williamston.

They sang them at protest meetings that were held in churches, and they sang them while they marched to the county courthouse. They sang them when they were in jail.

The photograph captures something important about where the power and drive of the civil rights movement was coming from in 1963.

Frinks looks watchful, ever vigilant. He looks mindful of all that is happening around the young activists whom he has shepherded to the March on Washington.

Jacquelyn Bond, on the other hand, is totally in the moment. She is holding nothing back. She is drawing from her deepest self, and she is giving it her all, as if God had told her that this, that moment, was her people’s time. That is a woman not afraid of anything on this Earth.

To learn more about the Williamston Freedom Movement, be sure to check out Amanda Hilliard Smith’s “The Williamston Freedom Movement: A North Carolina Town’s Struggle for Civil rights, 1957-1970.”

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.