I must have heard that phrase a million times when I was younger: “We were working in the logwoods.”

Old men would say it again and again when they remembered their younger days on the North Carolina coast. They talked plenty about farming and fishing and raising families, but they talked just as much about “working in the logwoods.”

Supporter Spotlight

Mostly they remembered how hard it was: how hot and how arduous and how dangerous.

I didn’t know much about it then, but I understand now that they were recalling a time when the roar of circular saws and the shrill holler of steam engines could be heard all across our coast.

Back then, lumber mill villages and sprawling logging camps sprang up almost overnight. You’d find them even in the deepest swamps. You’d find them in coastal communities in places that seemed on the edge of the world, like Goose Creek Island and the southern part of the Alligator River.

Over a little more than half a century, roughly from 1870 to 1940, the region’s whole landscape changed: millions of acres of forestlands were clear-cut and all but a few of the region’s old-growth forests vanished.

In those days, the North Carolina coast was home to thousands of loggers and sawmill workers. But they weren’t the only ones “working in the logwoods.” Many a farmer left his fields for at least a few weeks or months a year in the wintertime and trod into the woods, crosscut saw in hand.

Supporter Spotlight

Many a fisherman pulled his boat up on the shore and headed into the woods, too.

Sometimes the lumber mill was a giant complex of spinning blades and planers in coastal towns such as Beaufort, New Bern, Oriental, Elizabeth City and Swansboro.

Other times, big mills rose up on the edge of out-of-the-way creeks and rivers, far from any town or village.

I’m thinking of places such as the Roper Lumber Co.’s big mill that was located on Clubfoot Creek, near my family’s homeplace in Harlowe.

Yet other times the logging crew was simply a handful of men, a stubborn old mule and a two-man crosscut saw. Sometimes sleeping on stumps to stay above the swamp waters, they cut timber and sold it piece-rate to a sawmill maybe run by a neighbor in a backyard shed.

At least half a dozen of my great-uncles and a passel of my cousins worked in the logwoods in Craven and Carteret counties at one time or another.

I’m thinking about all this today because Vann Evans, the photographic archivist at the State Archives in Raleigh, wrote me recently to let me know about a spectacular collection of historical photographs of the lumber industry at the Forest History Society in Durham.

I immediately went through the Forest History Society’s collections in search of photographs from coastal North Carolina.

The Society’s archives includes photographs and manuscripts from across the U.S., but I found quite a few images of logging and lumber mills on our coast. Most were taken in the years from 1900 to 1950.

I’d like to share some of those photographs with you. I hope you enjoy them. As always, if you see things in the photographs that I didn’t see, or if you know things about the people or places in them that I missed, I’d love to hear from you.

Camp Perry, New Bern

A family in a high-wheeled cart in front of their cabin in a logging camp called Camp Perry near New Bern in 1908. They’re waiting for their driver, a quilt airing on the line. The cabin was probably an old sharecropper’s home and perhaps also the home of enslaved laborers before the Civil War.

Camp Perry was located on the Roper Lumber Co.’s holdings. Based in Norfolk, Virginia, the company owned outright more than 600,000 acres of forestland, as well as timber rights to 200,000 more acres.

The John L. Roper Lumber Co. seemed to be all over the North Carolina coast in those early years of the 20th century. It had mills in New Bern, Elizabeth City, Belhaven, Roper, Clubfoot Creek and Oriental, as well as near Norfolk and at least three other sites.

At that time, the Roper company was one of the largest lumber businesses in the U.S. Based just on the production at its white cedar mill in Roper, a town in Washington County named after company founder John L. Roper. It was at one time the country’s largest supplier of cedar shingles.

Mules and Log Rafts

Workers resting on a log behind a relatively small slip-tongue logging cart called a “high wheeler,” perhaps near New Bern, 1910. The men used this kind of high-wheeled cart to raise logs off the ground and carry them to a rail line or to a local creek or river where they could be floated to a mill.

In the photograph above, we see woodsmen and their mules getting a larger high wheeler into position to lift a log near New Bern, 1910-11.

A better view from behind of how the loggers used their mules and a slip-tongue logging cart to lift and carry pine logs. This was on the John L. Roper Co.’s timberland near New Bern 1910-13.

Below, we see a raft of yellow (longleaf) pine logs at a mill on either the Trent or Neuse rivers, in New Bern with the conveyor that hauls the logs into the mill in the foreground. The date of the photograph is 1910 or 1911.

At that time, New Bern was largely a lumber port, drawing rafts of logs from distant shores of the Trent and Neuse rivers and shipping most of them to northern seaports. Several large mills operated along the banks of the town’s two rivers, including one of the Roper Lumber Co.’s mills.

Steam and Rail

Taken sometime between 1910 and 1913, this photograph shows loggers using a traveling derrick to load logs onto a car on the Roper Lumber Co.’s railroad near New Bern.

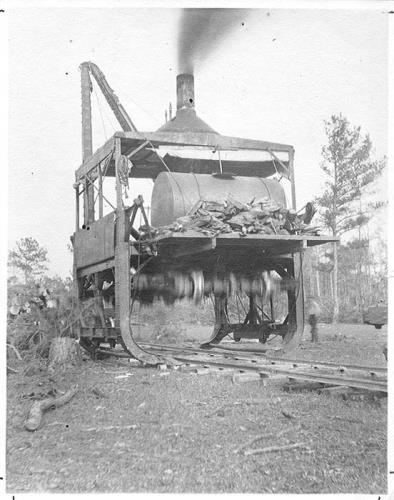

Below, a steam cable skidder in an unidentified forest in North Carolina in 1910. The machine was capable of running a 1,000-foot-long cable into the forest so that the workers could drag logs to the rail line. Building long narrow-gauge rail lines, loggers used steam skidders like this one in swamp forests and other woodlands where the rough ground conditions made it impractical to use oxen, horses or mules.

Below, is a McGiffert log loader in a forest near New Bern, almost certainly on lands owned by the Roper Lumber Co. in 1911. The combination of steam technology and the use of railroads was a critical factor in the lumber boom that swept through the North Carolina coast in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The McGiffert loader drew on both steam power and the rails. Invented by John R. McGiffert circa 1900 and manufactured by the Clyde Iron Works in Duluth, Minnesota, it was a massive, ungainly looking machine that rose off a railroad track and stood on stilts, as it is in this photograph.

The loader’s steam-powered boom lifted logs from either side of the track onto cable-drawn rail cars that passed into the tunnel created when the loader’s platform was raised off the tracks. When its job was done, the loggers removed the stilts and lowered its running wheels back on the track and ran down the rail line to another logging site.

The Great Dismal, the Roanoke & Lake Waccamaw

Below is a hand-colored view down a logging spur in the vicinity of the Great Dismal Swamp in 1922. The forests in the vicinity of the Great Dismal were some of the first areas in the state to be logged intensively. A forester estimated that the second-growth stand shown in this photograph had first been cut around 1800.

Below we see the Halifax Paper Co.’s mill in Roanoke Rapids in 1931. The company was one of the state’s first pulpwood manufacturers, taking largely pine logs, breaking them down into fibers and using them to make paper, cardboard and other products.

Below, is a bark-peeling machine at the Council Tool Co.’s yard in Wananish, in Columbus County in the 1930s. Wananish is now part of the town of Lake Waccamaw.

John P. Council founded the Council Tool. Co. in Wananish in 1884. Originally, he focused on making tools for the turpentine trade and eventually gained 90% of the market for those implements, at least in the U.S.

Still in business today, the Council Tool Co. specializes in making axes, mauls, sledgehammers and other tools particularly for use in forestry and firefighting.

The Council Tool Co. Records in the Archival Collections at North Carolina State’s library provide a fascinating look at one family’s story in the state’s wood products industry over more than 125 years.

Oxen and the Croatan

In this more recent photograph, dated 1940, we see a truck hauling loblolly pine logs down a plank road in the Croatan National Forest.

The Croatan National Forest covers parts of Craven, Carteret and Jones counties. The federal government acquired the area in November 1933.

The first and largest part of the national forest, totaling more than 50,000 acres, was acquired from Interstate Cooperage, a wood products subsidiary of Standard Oil that had a large mill in Belhaven.

Some parts of the Croatan have always been open to commercial logging. Other parts are preserved as wilderness and for recreational use. They include some breathtaking stretches of salt marsh, longleaf pine savanna, hardwood creek bottom and pocosin swamp that are some of my favorite places in the world.

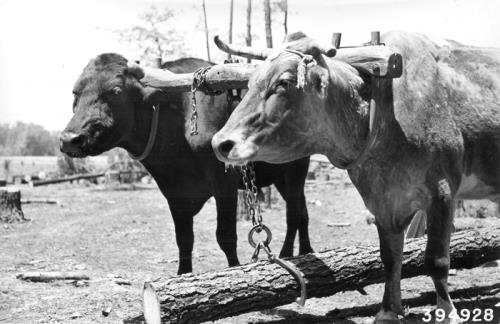

Here we get a close-up of an oxen team used in hauling logs bound for the Smith Lumber Co.’s mill near Smithfield in 1940.

Even in the era of steam and rail, oxen, mules and horses remained indispensable in most logging operations.

I’ve always heard that a good “snake horse,” so-called for their ability to haul logs through winding paths in dense forest and to step deftly over logging chains and lines without breaking stride, was a sight to see.

For most lumber companies, World War II marked the end of the use of oxen, mules and horses in logging operations.

The Strike at Greene Brothers

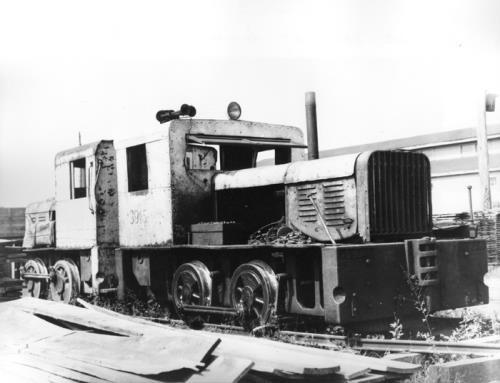

This is one of the locomotives that the Greene Brothers Lumber Co. in Elizabethtown used to haul logs to its mill in the 1950s. The train, a Vulcan No. 3195, was built by Vulcan Foundry Limited, a venerable English maker of locomotives that was founded in 1832.

In 1947, Greene Bros. was the site of a long strike and a bloody repression of timber and sawmill workers that had formed a labor union as part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO’s, “Operation Dixie” labor organizing campaign in eastern North Carolina.

Then the largest lumber mill in the South, the company paid its African American laborers less than $8 a day for working sunup to sundown. When the loggers and sawmill workers organized in 1947, the company refused to negotiate with their union, leading to a yearlong strike.

Urged on by the “Red Scare,” company supporters lashed out at the striking workers and accused them of being unpatriotic and communists, even though many of them were World War II veterans. Union supporters were fired, arrested, blacklisted, often beaten and sometimes evicted. A car was dynamited and shots fired into bedroom windows.

To learn more about the lumber workers’ strike in Elizabethtown and labor activism elsewhere in North Carolina’s lumber industry in that time period, see my story “Adelle McDowell: A Frightful Time” and most especially Will Jones’ “The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South.”

Note From the Author: Special thanks to Vann Evans at the State Archives of North Carolina and to the Forest History Society for making such wonderful photographs available to the general public. The Forest History Society is a nonprofit library and archive committed to preserving and sharing forest and conservation history. On the website, you can find everything from a digital database of historical photographs and manuscript collections to a middle school curriculum called “If Trees Could Talk.” The Society is located at 2925 Academy Road in Durham.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.