In recent years, Ron Sutherland, chief scientist for the Seattle-based Wildlands Network, has seen increasing numbers of coastal and warm-weather species of frogs and anoles around his home in Durham and in the Research Triangle Area.

“They’re moving (from the south and east) as the winters get warmer,” he recently told Coastal Review Online. “It’s fairly obvious if you look.”

Supporter Spotlight

In particular, he’s noted an increasing abundance of squirrel frogs and green anoles, which have long lived in warmer and more coastal, even tropical, climates.

“They didn’t use to be here in nearly such large numbers,” he said, and the latter are now widespread at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

But the change in the geographic distribution of critters isn’t limited to amphibians and reptiles. Some fish species are showing up in more northerly waters than in the past, said Sutherland. Manatees, famed in Florida, are making more appearances in North Carolina coastal waters, to the point where it’s almost normal to see them.

Armadillos – synonymous with Texas, according to the familiar song by Gary P. Nunn – are moving north and east and have been spotted in western North Carolina.

If they are moving, so are larger animals, like bears and wolves and foxes, not only because of climate change, but also because of rampant habitat loss as cities and towns sprawl into areas that once were wild, said Sutherland.

Supporter Spotlight

But the questions arise, how to protect these species? How to connect old habitats to potential new ones, across countless ever-growing ribbons of highways that serve hordes of pedal-to-the-metal motorists east of the Mississippi River? How, indeed, to preserve what’s left of wildlife in the East?

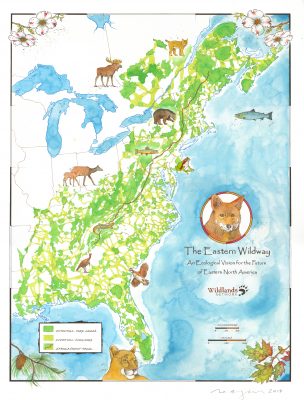

The Wildlands Network recently released a map, called the Eastern Wildway, which it announced Oct. 22 as “a bold vision for reconnecting and restoring wildlife habitat across eastern North America.” It’s a counterpart to the organization’s existing Western Wildway Map.

The new map covers much of the eastern North America, which the organization says is “home to a broad diversity of wildlife, including red wolves, Canada lynx, cougars, martens and other native carnivores. Many resident plants, birds, fish, salamanders, and butterflies are found nowhere else on Earth.”

The map is among the first large-scale conservation plans to show an ecologically prioritized, cross-section view of an entire continent, specifically the populous yet biodiverse eastern side of North America.

The map, Sutherland said, is intended to be “inspirational,” a way to encourage people and organizations to voluntarily protect existing habitats and find ways to connect them. He recently handed out 350 copies at a national land trust rally sponsored by The Nature Conservancy in Raleigh. Among the trusts represented were the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, based in Wilmington and New Bern, which works to protect the state’s coastal habitat.

The dream, Sutherland said, is simple, the ambition big and the difficulty of achieving it high. But the need is great. A 2015 report by the Center for American Progress found that one in five species in the United States is threatened to become extinct because of habitat loss, fragmentation and climate change.

“Wildlands Network’s Wildway concept offers a solution for protecting native plants and animals by connecting the wild spaces these species need to survive, and supports renowned Harvard Biologist E.O. Wilson’s vision of designating ‘Half-Earth’ for nature in order to safeguard our planet’s biodiversity,” according to the announcement.

The goal, simply put, is to find ways to connect cores – large areas of intact natural habitat – through corridors, which wouldn’t be off-limits to people, to other cores.

The idea is to use existing parks, national forests and other protected areas, as well privately owned lands, and to get wildlife organizations, land trusts and conservancies and other environmental groups to help find ways to connect those. There’s also the chance, Sutherland said, of getting government funds.

“We’re proud of the way we’ve used the best available science to map out a robust vision for saving 85% or more of the biodiversity of the East Coast from extinction,” Sutherland said in a statement. “If protected, the Eastern Wildway habitat network would allow almost all native species to survive the ravages of rapid climate change and habitat destruction.”

Sutherland said he knows the federal government, as presently configured, and some state governments won’t be amenable to spending money. But, he said, there is bipartisan support in Congress for better funding of wildlife protection, noting as examples Reps. Don Beyer, D-Va., and Vern Buchanan, R-Fla., and Sen. Tom Udall, D-N.M. In May, they introduced the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act of 2019.

Sutherland also has hope that state governments will eventually see the wisdom of the idea and goal and commit more funds to habitat protection.

Finally, he said there are possibilities to induce substantial incentives for private landowners to participate voluntarily in protecting natural habitats and to encourage “significant ecological restoration, such as replanting native vegetation to establish wildlife corridors and expand core natural areas to sufficient size.”

Sutherland may be best known for his efforts to reintroduce and save red wolves in North Carolina and his successful efforts a few years ago with North Carolina State University’s forestry and environmental resources professor Fred Cubbage to keep the university from selling and allowing development of its Hofmann Research Forest in Jones and Onslow counties. Sutherland said he knows the challenges ahead.

“But there are,” he said, “a lot of people who believe in this concept.”

The key will be getting those people to work together, to commit to making it eventually happen, he said. Even under the best of circumstances, he said, it will take “a few decades, or more.”

But it’s not an impossible dream. Sutherland said he’s buoyed that conservation and environmental groups in North Carolina, ranging from those dedicated to protecting scenic rivers in the mountains to those in the east protecting coastal waters, believe in habitat protection for wildlife.

The groups have, he said, seen “large-scale development coming in” for decades, and understand the risks of not responding quickly.

“Once it’s gone,” he said of habitat, “it’s harder to get it back” than it would have been to protect it initially.

That problem is often particularly acute along the coast, he said, because as coastal cities grow, they can’t go farther east – the waters stop them. To expand, they must go west, tearing into habitat between their existing boundaries and those of towns farther inland.

It’s clear, Sutherland said, that time is of the essence to protect habitat. The longer it takes, the less land there is to protect and the less chance there is to make the crucial connections between them.

He said it will be important to mitigate barriers to animal migration, such as highways, using proven techniques like wildlife overpasses and underpasses. Fencing can also be used to keep wildlife off roads and funnel animals to the crossings.

There are, Sutherland said, plenty of examples where those things have worked. Examples include Canada’s Banff National Park, which is separated by the Trans-Canada Highway; along Interstate 75 in Collier and Lee counties in southern Florida; and in southern California.

The Florida crossings are largely intended for endangered Florida panther, but also benefit bobcats, deer and raccoons. In California, crossings work for bobcats, coyotes, gray fox, mule deer and long-tailed weasels, in such places as Orange, Riverside and Los Angeles counties. In Banff National Park in Canada, they aid deer, elk, black bear, grizzly bear, mountain lions, wolves, moose and coyotes.

Advocates say the crossings also reduce the incidence of dangerous and sometimes deadly – to humans and wildlife – vehicle-animal collisions.

The Eastern Wildway map, Sutherland said, serves as a blueprint for how and where all of this could work.

“The biggest challenge,” Sutherland said, is “to identify the species most at risk,” and begin, as soon as possible, steps to protect them.

He said the Wildway map is a tool to help that process.

Wildlands Network Eastern Program Director Christine Laporte put it this way: “This is a unique and high-value resource for anyone working on conservation in eastern North America. We invite partners to contact us to see how it can provide inspiration and robust scientific information for your work.”

Sutherland said the Wildlands Network staff had been talking about the wildway concept even before he arrived, but got serious about the Eastern project in early 2017.

To create the Eastern Wildway Map, Wildlands Network used a wide range of existing datasets and feedback from conservationists across the region. Data sources include Wildlands Network’s own connectivity models, as well as state and federal agencies, other groups, such as The Nature Conservancy and The Wilderness Society, and academic researchers.

“It took a lot of work by a lot of people,” Sutherland said. “We’re proud of it.”