This story has been updated to clarify that kudzu is not federally recognized as a noxious weed.

CHADBOURN — As the threats and damages from wildfires and storms have been intensified by climate change, the growing danger from invasive plants and animals is rarely a compelling headline. But with the final suspension on Oct. 1 of a federal scientific panel on invasive species, experts warn that more, not less, attention must be dedicated to forestalling future economic and environmental devastation from the invaders.

Supporter Spotlight

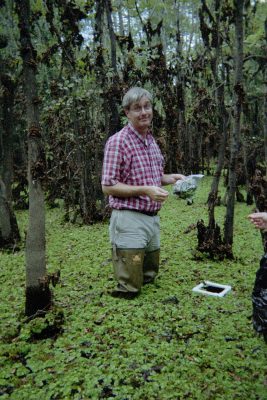

“We’re just sitting on the edge of an absolute mess,” said Randy Westbrooks, a biologist and invasive species prevention specialist based in Chadbourn.

Westbrooks, who had worked for the federal government from 1979-2012, was an original member of the now “administratively inactive” Invasive Species Advisory Committee. Started 20 years ago, the 12- to 16-member panel made recommendations to the U.S. Department of the Interior’s National Invasive Species Council, or NISC.

The advisory committee also produced numerous scientific white papers on issues related to invasive species, such as marine bioinvasions, e-commerce and climate change.

“We need those committees,” he said.

Invasive weeds such as hydrilla and phragmites are a continual issue in North Carolina, as well as animals such as lionfish, carp and wild hogs. But Westbrooks said that there are also looming risks to the state such as from red ambrosia beetle, the vector for the fungus that causes laurel wilt disease, and cogongrass, “a horrible plant” that has invaded the pine savannas in Alabama and Georgia.

Supporter Spotlight

“Without an external committee providing expert recommendations to NISC, effective NISC-agency policies and programs are at risk in an environment of already heightened and increasing threats and risks from invasive species to human health and welfare, ecosystem stability, food security, and commerce,” said a committee memo submitted in May to the council.

It’s not so unusual for committees to come and go in government, Westbrooks said; it’s that a big, multi-jurisdictional problem such as invasive species requires inbuilt collaboration, continuity and financial resources to be effective. It was that type of cooperative effort that limited the spread in North Carolina of beach vitex, a coastal grass that forms mats that choke out native species and inhibit sea turtle nesting, and witchweed, a parasitic weed that can do serious harm to corn and other agriculture.

Then-Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, who had served from 1993 to 2001, Westbrooks said, “got it.”

“The invasion of noxious alien species wreaks a level of havoc on America’s environment and economy that is matched only by damage caused by floods, earthquakes, mudslides, hurricanes, and wildfire,” Babbitt said in an April 1998 statement. “These aliens are quiet opportunists, spreading in a slow motion explosion.”

As Westbrooks recalled, Babbitt gave the experts the support and funds, opening what he characterized as the “golden age” of invasive species management.

Now, while his consulting work has him interacting with academics, nonprofits and government agencies, he sometimes gets frustrated with dismissive attitudes about invasive species that he has heard.

“‘Why you so worried about weeds?’ they’ll say,” Westbrooks recounted. “‘Weeds are a local problem. You know what we need to do on public lands? Drill for oil!’”

Westbrooks cited a study by Western Australia scientist Rod Randall, who documented 36,000 species of invasive plants worldwide. Of that, Westbrooks said about 3,000 have been introduced in the U.S. “That means there are 30,000 weeds in the world that are not here yet.” But once they’re here, he said, they’re difficult to eradicate.

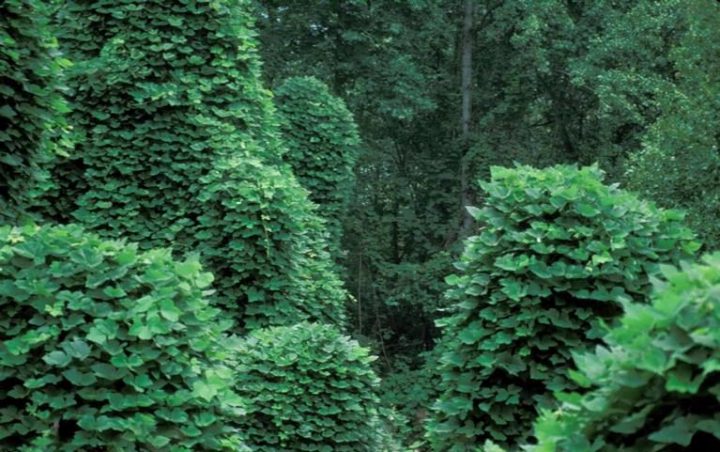

That lesson was learned with kudzu. When it was first brought from Japan to the U.S. in 1876, it was valued as an ornamental vine. During the Depression and World War II, it was planted it to control erosion in prairie and farm lands. Within decades, the aggressive vine had climbed its way onto numerous invasive weed lists.

Before long, it was known as the “plant that ate the South.”

Kudzu is not on the federal noxious weed list because of its widespread proliferation but some states, including Florida and New York, recognize it as a noxious weed.

“It took until the 1960s to understand it was the stupidest thing to do,” Westbrooks said about the earlier importation and planting of the weed.

According to a 2011 advisory committee white paper on marine invaders, invasive species are second only to habitat destruction in creating danger to native species, loss of global biodiversity and causing severe and permanent damage to ecosystems.

Some of the awful consequences the paper cites include degradation of the aesthetic quality of our natural resources and the carrying or supporting harmful pathogens and parasites that could affect wildlife and human health.

In a December 2010 paper, the committee warned that climate change effects can amplify the negative impacts of invasive species, setting up little-understood interactions.

“They can result in threats to critical ecosystem functions on which our food system and other essential provisions and services depend, as well as increase threats to human health,” according to the paper. “However, unless we recognize and act on the impact of climate change and its interaction with ecosystems and invasive species, we will fall further behind in our effort to prevent, eradicate, and manage invasive species.”

Chuck Bargeron, co-director of the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia, had been serving as the Invasive Species Advisory Committee chairman when the committee learned in April 2019 that it would be suspended. According to the May memo submitted to the council, the committee was told that the action stemmed from lack of funds and staff capacity to maintain its operations.

At the same time, control of invasive species is requiring more government resources.

“The problem is only getting worse,” Bargeron said. “But it is a problem that is drastically underfunded.”

Bargeron said that the committee, composed of 12-16 volunteers with expertise in invasive species, met twice a year. Travel expenses were reimbursed.

“If nothing else, an advisory panel like this draws attention to the issue and that’s important,” he said. “I served on it for six years and there were some really good people involved with the committee and we produced some really good work … It’s one of the many tools to help with the fight against invasive species.

“I think more can be done across the board to help fight the invasive species issue,” Bargeron said. “Collectively, more should be done to protect the public now and for the future.”