“You know in your heart if you are a ‘Promise Lander.’ There is salt water in your veins. The salt air calls you home. Your blood rushes when there is a ‘nor easter’ or shifting of the wind. Hearing ‘the fish are gonna run,’ and only a Promise Lander would understand what that means. The shrieking of a shore bird, egret, or sea gull – it’s like a special language that only you understand,” Janice Ray Lewis Ditto writes in “You Know in Your Heart if You Are a Promise Lander” featured in the book, “The Promise Land Vol. 1.”

“While times have changed and the life they knew then is gone, Ditto continued, “No one can take away our memories. We can still see and hear, in our hearts, if we try, the giggling of little children as we play at the shore, sea gulls flying overheard, fishermen coming in from the day’s work, the sun almost going down and Mama calling us home for supper.”

Supporter Spotlight

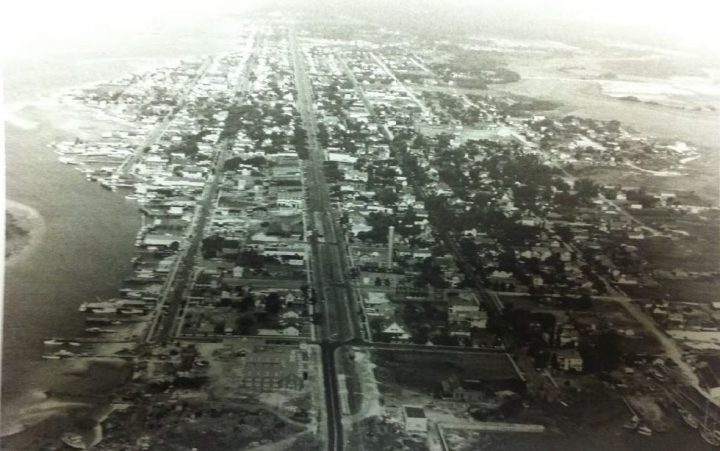

The Promise Land is situated between 10th and 15th streets and from the train tracks on Arendell Street to Bogue Sound in Morehead City. Morehead City was a relatively new town planned by John Motley Morehead at the turn of the 20th century when Cape Bankers, pronounced Ca’e Bankers, forged a new life there, as well as on Harkers Island and Bogue Banks.

“On a strand of beach called Shackleford, twelve miles long, and less than a mile wide, running from Beaufort Inlet to the Cape of Lookout, were five villages – – Diamond City, Belle’s Island, Wade’s Shore, Whale Creek and the Mullet Pond. Seventy-five families lived in these villages and the livelihood of these folk was fishing, whaling and hunting. Fishing was done when the fish ran plentiful, particularly in the fall season. Whaling was one of the biggest jobs and, though hard and dangerous, brought good pay. Hunting was done at random by young and old alike, for deer and wild boar were plentiful,” Clifton Guthrie explained in“Six for the Sea, The Crissie Wright Time” in “The Promise Land Vol. 1.”

“In the late 1800’s hurricanes began hitting the islands with increasing frequency and strength, causing much damage from the over wash and winds. The weather, combined with the decline of whaling in the area, had made it very difficult for these hardworking fisherman and their families to continue living on the islands,” Julia Gould Charles wrote in Vol. 1’s “The Abram Lewis Home – 1205 Evans Street.”

But, “This is not to say that storms and scarcity of whales were the only factors that contributed to the exit of bankers to mainland communities. One must certainly cite that better opportunities for work and education were also factors. Other scarcities like wood for cooking and heating and the over hunting of game like, deer, bear and water fowl might also have worked to force the islanders to seek newer and better ‘hunting grounds’ elsewhere,” wrote Bob Guthrie in “Tom Thomas Guthrie not Tom Thomas Moore” in “The Promise Land Vol. 1.”

Guthrie has deep roots in Carteret County and currently serves as the secretary/treasurer for the Promise Land Society, which is hosting a homecoming 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Oct. 26 as part of its effort to preserve the heritage Ditto writes about and shares with so many others.

Supporter Spotlight

The homecoming will be held at Martin Luther King Jr. City Park and the Morehead City train depot, both on the 1000 block of Arendell Street. There will be tours of the Promise Land neighborhood, live music, storytelling, history exhibits, food truck, vendors and fellowship.

“The festival is to make non-Promise Landers aware of the Promise Land. … and tell tall tales about the Promise Land and its people,” Guthrie told Coastal Review Online.

Shannon Adams, vice president of the Promise Land Society, which was established in 2012, said one of their missions of the society is to bring awareness of the historical significance of the struggles and “toughness” of the original inhabitants of Carteret County.

“We’ve released two books to bring awareness and the festival is meant to do the same – to get people to learn about our rich heritage,” he said. Both volumes of “The Promise Land” are available at Chalk & Gibbs and History Museum of Carteret County, both in Morehead City.

Sharon Orleans Lawrence in “Exodus of the Ca’e Bankers,” featured in Vol. 2 and first printed in Maritimes Magazine June 12, 1986, writes that the communities in Carteret County settled by Ca’e Bankers have always had a mystique, a reputation, a recognized uniqueness.

“Their residents are people whose lives were inextricably bound to the water, both because of its proximity and because the sea was their livelihood. They are a clannish people, strong-willed, strongminded, out-spoken, and open-hearted,” she wrote.

“A melodious brogue thick with metaphor rolls off their tongue from deep in their throats and makes everyday conversation an experience worth remembering. These are the people of Harkers Island, Salter Path, and in Morehead City, The Promise Land. They share a common character because they share common ancestry – the seafaring folk of the Cape Banks, those islands of the Outer Banks that run west and north from Cape Lookout including Shackleford Banks. Almost 100 years after the last of their ‘Ca’e Banker’ (derived from Cape Banks) ancestors moved off those Banks, the roots of their memories still cling to those islands,” Lawrence continued.

Of the handful of communities on Cape Banks the largest, located on the east end of Shackleford, was Diamond City, named after the black and white diamonds on Cape Lookout Lighthouse, and at its peak, the population of the village was about 500.

A series of devastating hurricanes, with the first two in 1878, followed by another in 1879, three in 1897, and then two more in 1899, “all of which hit the Banks broadside. The maritime forest began dying, the sand began drifting over and killing the greenery, and the exodus from the Banks began. By 1905, all that was left of Diamond City was a ghost town,” Lawrence wrote. Many of these settlers floated their houses to their new home on scows and flat barges, and some even moved the graves of their relatives from the graveyard on Shackleford to the mainland.

Alida Willis wrote during the 1970s “Promise Land – History of the Migration” included in “The Promise Land Vol. 1,” that while the Bankers were “of the same stock as the inhabitants of the other villages along the waterways of Carteret County, the new town of Morehead City to which they had come was already populated with a much different and more varied group of people,” she wrote.

The diverse population was made up of “the venturesome who had responded to John Motley Morehead’s exhortation to invest in ‘the first instance of an entire new city on the Atlantic coast being brought into market at once!’”

These were railroad investors, land speculators, merchants, itinerant tradesmen, farm-based families and others, many working to rebuild their lives after the Civil War, and they were all wary of the Cape Bankers, who literally sailed their small homes up Bogue Sound, according to Willis.

“To the Bankers, it was imminently practical to take their houses with them – they had built them by hand in a fashion to allow dismantling and reassembly. But to Morehead residents, it was unheard of for an entire community to move to a new location across bodies of water and to take their homes with them over these waters.”

The Bankers brought with them a dialect, their customs and “a lifestyle dictated by their near isolation in a harsh world where survival was a constant challenge,” Willis wrote.

Ditto recalls the reception of her ancestors to Morehead City.

“When our forefathers came to Morehead to the Promise Land the people living here thought we were illiterate and eccentric. They didn’t understand the way we talked or the way we did things. They described us as the poor people that lived down by the water and really they didn’t want anything to do with us. So once again we learned to survive by becoming a self-sufficient little village. We built our own church. Old Daddy Kib Guthrie started a grocery store. Aunt ‘Riny’ Marina Ann Guthrie, became a midwife. We had carpenters, electricians and plumbers. Whatever you needed, you got help from your own. I think we did pretty good,” she wrote.

The Promise Land Society’s homecoming being held “To preserve and communicate the historical legacy of the land and people of the Promise Land to all that will listen,” will feature performances at 10 a.m. by Landfall Band and at 1 p.m. with the George Ballou Band, vendors, Promise Land Tours for a donation with Society President Rodney Kemp at 9 a.m., 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. and at 2 p.m., the Fish House Liars will take the stage.

Kemp, a storyteller who has studied Carteret County history for decades, told Coastal Review Online that fish house lies are a “Carteret County tradition of storytelling, we don’t let the truth get in the way of a good punchline. You have to use your imagination to find the truth in it.” He said he learned the style from the great storytellers of Carteret County.

The homecoming is important for those who have ties to the Promise Land community, Kemp said. Those folks who don’t live in the area are able to come home and reminiscence, plus they get to see everyone in the Promise Land. “About everyone is kin to each other,” he added.

For those folks who don’t know much about the Promise Land, Kemp recommends joining him on the neighborhood tours aboard a bus, when he will talk about historic sites and buildings and teach them about the Promise Land. Also for those new to the area who want to learn more, they can visit the historical exhibitions.

Kemp said in an interview Tuesday that the grandparents of many in the Promise Land Society are the ones that moved to Morehead City from the Banks, and “They talk history about three or four generations before that,” he said, adding that “There’ve been people living on the Banks since the 1700s.”

Adams is one of those Promise Land Society members with roots. He has been a force behind the organization since its inception May 2012, just after he purchased the cottage at 1311 Shackleford St. that his great-grandfather Cagie Adams built in 1918.

“He had a boatbuilding yard on the shore at the end of 14th Street. When my father, Ray Adams, was a child, my great-grandfather taught him carpentry. Ironically, my father is the one who fully restored the cottage when we purchased it,” he said.

The first festival was in October 2012 and since then, they’ve alternated between a festival and homecoming, with the festival, which is being held this year, being more involved, but are always held the last Saturday of October.

“We have music, storytellers, photo slideshows, and census maps showing who lived in the Promise Land in 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940. Also, we’ll have music and local vendors selling coastal themed merchandise and wares,” Adams said.

And how did Promise Land get its name? There are a handful of theories that Lawrence explored in “Exodus of the Ca’e Bankers.”

“They say there was a man named Smith who used to walk home at night, slightly tipsy, singing lustily that he was ‘Bound For the Promised Land.’ Another version recalls that when the poor Bankers settled in Morehead City, they purchased their 50’x100’ lots from the Shepard’s Point Land Company and promised to pay. The promise was realized slowly, and the businessmen facetiously referred to the area as The Promise Land.

“The most popular version, and possibly the more accurate one, is that the beleaguered Bankers who moved to the mainland saw it as a haven safe from storms, and they compared it to the biblical Promised Land where the Israelites finally found rest. As the boats carrying the thankful Bankers and their possessions sailed landward, the people sang the old hymn, ‘I’m Bound for the Promised Land.’ Regardless of the origin of the name, descendants of Ca’e Banks blood do not add the ‘d’ on the end of the word ‘Promise.’ It is The Promise Land.”