In Kitty Hawk, the encroaching waters of Kitty Hawk Bay threaten to close Moor Shore Road, one of the oldest roads on the Outer Banks.

For lifelong resident Amy Wells, the rising waters and disappearing shoreline is something she has observed over her lifetime.

Supporter Spotlight

“Along Moor Shore road there were trees. My father had aerial photos, you could see there were trees out there. That was in the 1970s,” she said.

Moor Shore Road is a short but beautiful road that parallels Kitty Hawk Bay. One of the oldest roads on the Outer Banks, it is the route the Wright Brothers traveled to get from Bill Tate’s house in Kitty Hawk to their campsite at the base of Kill Devil Hill.

At one time the road was on the north end of a series of roads and paths that followed the shoreline of Roanoke Sound, connecting Nags Head and Kitty Hawk.

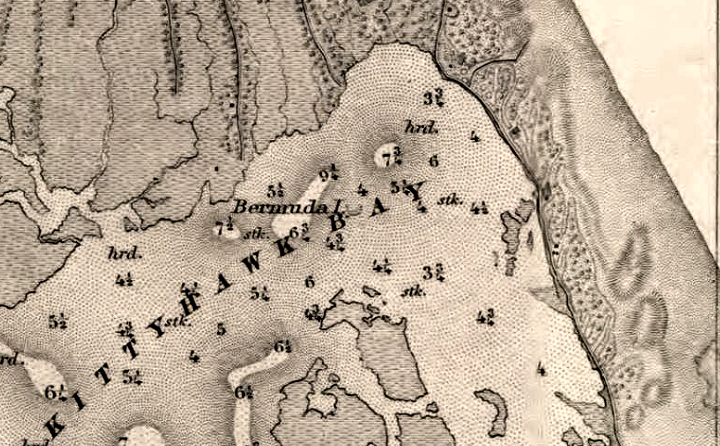

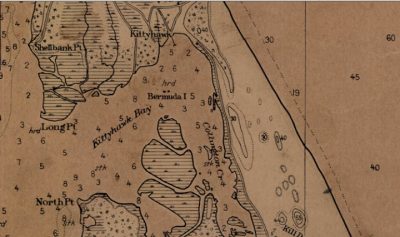

A United States Geological Survey map as early as 1876 shows a road paralleling Kitty Hawk Bay, and a 1938 state Department of Transportation map depicts Moor Shore Road.

More easily seen in the highway map, but in all of those early maps, one thing is apparent: there is a marsh or land between the water and the road.

Supporter Spotlight

The road is important even today. In November, it is part of the Outer Banks Marathon. In the summer, when traffic is backed up on the main roads, it is a welcome if brief respite from the madness of summer traffic. When ocean overwash from tropical storms or nor’easters close the main roads in Kitty Hawk, it is part of an emergency route that allows traffic to keep moving.

To protect the road, a living shoreline is being constructed.

Living shorelines deflect and dissipate wave energy through offset sills or breakwaters, allowing sediment to accrete on the landward side of the protection. As the sediment increases, grasses and reeds take root recreating the marsh that was lost. The plants of the marsh further dissipate wave energy.

Although an effective means of shoreline protection, there are limits to what a living shoreline can accomplish.

“The way that water is pushed into a system is critical. They’re not going to stop a 10-foot or 20-foot storm surge,” explained Erin Fleckenstein, coastal scientist and manager of the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s northeast regional office in Wanchese.

Hardened structures like bulkheads can be effective in certain situations, but they can create significant environmental damage.

Bulkheads work by deflecting wave energy, but do very little to dissipate the energy. Typically that energy goes to either side or in some cases, down. After a few years, land on either side of the bulkhead often shows significant erosion, or land behind a bulkhead is sometimes eroded.

Carlos Gomez of Coastal Engineering noted what he has seen with bulkheads.

“They put in a bulkhead and in five years they have no marsh,” he said.

It is an ambitious undertaking. At almost 700 feet, it is significantly larger than most living shoreline projects. The $270,000 cost of the project and how residents, federal, state and local governments came together seems to set this project apart from others.

“The number of entities involved in this, I don’t think I’ve seen this before. And I doubt many of us have seen it,” Kitty Hawk Mayor Gary Perry said. “And it all started with a homeowner that said it will also benefit the greater good and the public, so the public trust entering into this is not untoward.”

As a homeowner with property facing Kitty Hawk Bay on Moor Shore Road, Wells knew the marsh had disappeared and that the road was prone to flooding.

She had become aware of living shorelines as a method of shoreline protection from volunteer work she had done with the University of North Carolina Outer Banks Field Site, a precursor to the Coastal Studies Institute. The lessons stayed with her and as she witnessed the disappearance of the marsh, she came to the conclusion that a living shoreline would be the best way to protect her property.

“I had seen it through the UNC Field Site,” she recalled. “That’s how it all got started.”

One of the lessons she took from working with the field site was how important it was to engage the public.

“They had what seemed like a real incentive to do (projects) where there was a real public exposure. So maybe somebody else could see it,” she said.

And Moor Shore seemed like the perfect location for that visibility. She had made the decision that even if she was the only property owner on the road with a living shoreline, she was going to install one.

“If nobody else wants to do it, I wanted to try it. It’s kind of a visible piece, where people can see it, and if it works, maybe somebody else would see it,” Wells said.

She had, in the past, worked with Gomez, an engineer, and mentioned to him she felt her property would be a good candidate for a living shoreline.

Gomez was familiar with the concept of living shorelines but had not worked with them, however a 2015 North Carolina Coastal Federation seminar in Columbia convinced him Well’s idea was worth pursuing.

“After the workshop (Gomez) reached out to me to see if Amy’s property would be a good candidate for a living shoreline,” Fleckenstein said. “I said it could be, but would be more effective if we could work with the neighbors to extend it along that whole stretch of road.”

“Her property was (only) 75-100 feet wide,” Gomez said. “Talking to Amy, I said, ‘Maybe we can talk to other people.’”

“I could tell the man on the other side of me (north), he really didn’t want a hardened structure there,” Wells said.

Other property owners also signed on and the project was selected for a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration cost share on living shorelines with private property owners.

With the NOAA grant in hand, Gomez and the federation made a presentation to the town of Kitty Hawk. The presentation went very well.

“We budgeted $180,000,” Perry said. The funds, he pointed out, are to protect access to properties that rely solely on Moor Shore Road.

“We’re saving the road, we’re not saving the property,” he said.

Although property owners were concerned about protecting land, a significant portion of funds for the project are dedicated to protecting infrastructure, which is how NCDOT became involved.

According to Perry and Fleckenstein, Kitty Hawk and the federation approached NCDOT about the project. There was interest, and for the first time the state’s transportation department contributed to a living shoreline as a way to protect a road.

“NCDOT is … contributing about $30,000 on the $270,000 project,” NCDOT Public Information Officer Tim Hass said. “We’re certainly at the table on this one, and we certainly have an interest in protecting the road and seeing how well this project works …”

Dare County also contributed to the project, Fleckenstein said, “An application was submitted to the Dare Soil and Water CCAP (Community Conservation Assistance Program) grant in August 2017 for additional cost share funds.”

With so many funding sources, some of the money Kitty Hawk has earmarked may not be needed, although it will remain available.

“Right now we’re coming in under that ($180,000 town grant) … If they should run short, we maybe can help with that,” Perry said.

The permitting process for the project has been unusually drawn out, something Fleckenstein acknowledged.

“It did have a lengthy permit process,” she said. “Part of the hurdle we overcame was there were a lot of moving parts and pieces. A lot of people involved and trying to keep everyone coordinated and moving toward the same end goal.”

After two years, though, the sills are being installed. With the nearshore protected from the full force of the wave energy, phase two will soon follow.

“The sills should be in place by March 2019 and marsh grass plantings will occur this summer and next,” Fleckenstein said.