It’s rare that the public gets to know the public servant behind a National Park Service uniform, and Doug Stover was no exception.

When he retired five years ago from his position as cultural historian at Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Stover had gained high regard throughout the communities and the agency he had served for 32 years, leading him to his current role as a consultant for the United Nations reviewing protection of world heritage sites.

Supporter Spotlight

Thanks to his friendly, regular-guy manner and modest persona, few knew that he has traveled to 65 countries and all seven continents; that he has interacted with kings and presidents; that he is an international expert on water lilies; that he is a trained wildlands firefighter and deep sea diver; that he has edited or written six books; and to top it off, that he has survived a close encounter with a panicked grizzly bear.

“He’s a little hidden treasure,” said Warren Wrenn, a National Park Service Outer Banks Group park ranger who retired the same year as Stover. “The package that you see is not necessarily the package that’s there. There’s a lot more layers than you see.”

One hint that Stover would not follow the typical career path was that his first adult job was at The White House. Before long, he was designing its gardens and working on official state events. At a subsequent post, he was the first person to catalogue thousands of writings in Frederick Douglass’ library.

Even after his park service retirement, he segued immediately into a consultant job for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, which requires hopping around the world from ancient temples to imperial palaces to phenomenal natural treasures.

But now Stover is ready to downshift.

Supporter Spotlight

“I just got back from Paris, reviewing the new fence wall under construction at the Eiffel Tower in Paris,” he wrote in an October email, “(and) the train to London for a World Heritage meeting at The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.”

Just the month before, he had attended the UNESCO World Heritage site visits to Amsterdam’s 17th-century Canal Ring, Mill Network at Kinderdijk-Elshout, Netherlands, Bruhl Palaces, Germany, and the UNESCO meeting in Lucerne, Switzerland.

“Plan on slowing down in 2019,” Stover wrote, maybe doing just four to six projects a year instead of 12-plus. At age 60, he wants to spend more time with his wife, Joan, whom he married in 1983, and his daughter Jennifer and grandson Mason.

During a recent interview at his sunny Nags Head home, Stover pulled out several huge binders, filled with meticulously organized photographs, news clippings and letters documenting his career.

As he browsed past a picture of George H.W. Bush (“I think he was doing some kind of tree planting,”) pictures from the Rose Garden (“As you can see, there’s not many roses to it”), memories bubbled up.

There was the time that someone told him about a loud insect sitting inside one of the plants in the Reagans’ bedroom, he recounted, and after some back-and-forth, Stover was informed that he would have to sneak the plant out of the room. “We know the First Lady gets up to use the bathroom at about 4 a.m,” he said. “I remember grabbing that plant and Ronald Reagan was sleeping.”

Back then, Secret Service “wasn’t as tense,” he recalled, and things were more relaxed.

“Mrs. Reagan was really into the plants,” Stover remembered. “Everything was first class then in the White House. Everything had to be perfect.”

He also interacted quite a lot with Hillary Clinton, who he described as quiet and not as particular about the gardens. Clinton later wrote a recommendation for Stover’s UNESCO job.

A native of Cohasset, Massachusetts, Stover, who has a degree in museum studies and landscape architectural design, started at The White House as an intern maintaining the grounds, and was later hired as a landscape architect. While he was being interviewed on a frigid December day in 1980, he said he remembers looking out the window at the South Lawn, where President Jimmy Carter was watching Peggy Fleming ice skate on a portable rink as part of a special event for White House staff.

During his six years at The White House, it was not unusual to work 15-hour days, often seven days a week.

“I would sit on the patio chair in the Rose Garden and do my drawings,” Stover recalled. “I’d look up and see Reagan in the Oval Office. You could look right in.”

Even after he left The White House, he would be called on occasion to help out with garden tours or special events. One time he went back to help Michelle Obama with garden beds.

As he moved on to National Capital Parks-East, more than a dozen National Park units in Washington, D.C., and Maryland, Stover carved out two remarkable niches. It was there where he developed a fortuitous friendship with Robert Stanton, who had served as National Capital Region Regional Director from 1988 to 1997, and National Park Service director from 1997 to 2001.

At Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens, Stover was asked how to get water lilies to bloom in the fall, so school kids could see them when they visit. That inquiry took Stover on a two-year quest that included consultation with the Smithsonian Gardens horticulturalists to develop a chemical solution that preserved the flowers. The news of the development spread quickly in the water lily community.

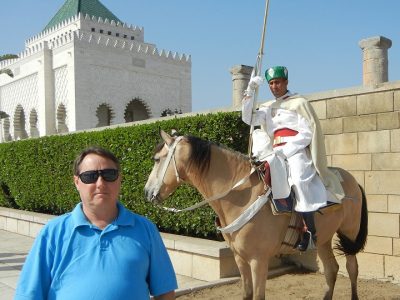

“Suddenly I’m being invited all over the world to teach them,” Stover said, adding that Stanton wrote an agreement giving him permission to attend international water lily symposiums and programs. For 20 years, he traveled to such sites as the water gardens of the Taj Mahal, India, and the Moroccan Palace, where King Mohammed VI told him he had surfed in Cape Hatteras and showed off an old WRV T-shirt.

When an opening for a museum curator came up at Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Stover decided to apply and was hired. He was assigned the enormous, and humbling, task of creating a bibliography of Douglass’ library collection. Incredibly, no one had recorded what was in the collection that included more than 2,200 books, leaflets and other materials, so Stover often found never-seen handwritten notes by the famous abolitionist tucked inside books.

After about five years, Stover accepted a job as curator for the 13 parks at National Capital Parks – East in the Washington, D.C., and Maryland area. In 2000, agency director Stanton asked him to go to the Outer Banks on 120-day detail to assist with the cultural resource planning for the centennial of the 1903 Wright brothers first flight. As it turned out, he never left.

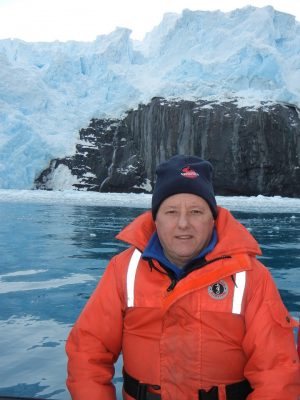

Along with his regular duties as cultural resources manager and park historian for the Outer Banks Group, Stover was also working for the National Park Service international affairs office helping countries that needed assistance in creating a national park, as well as a consult contractor for the United Nations and United States Government on cultural resources projects. Mysterious packages would be delivered to the office, Stover recalled, and the next thing his coworkers knew, he’d be on a plane to South Africa or Antarctica.

“They thought I worked for the CIA,” he said, laughing.

Since Stover was never one to talk much about himself, that secret agent theory was one of the favorite of his park service colleagues, recalled Wrenn.

Wrenn said he loved to weave stories around the mystery of Stover’s comings and goings.

“What better person can you imagine?” Wrenn joked in a recent phone interview. “Hired by the CIA, using a flower as cover, and come back as a park ranger!”

Stover’s magic, Wrenn said, is rooted in his ability to respectfully listen to people. Stover, he said, doesn’t brag, he doesn’t step on toes, and he doesn’t shy from challenges. But he always keeps his eyes open for opportunity and connections. “The thing about Doug,” Wrenn observed, “he knew enough people at the right places.”

And, he added, Stover was always good-natured about teasing.

“That’s one thing about Doug,” he said. “He couldn’t care less. He rolled with everything.”

In 2015, Stover’s 28-year-old son Andy died. At his service, Stover showed a slide show in honor of his son’s life. Born with cerebral palsy, Andy could not talk and was confined to a wheelchair. But his parents said he was a good listener and seemed to understand a lot. He was popular at school and was proud to attend the prom. He especially enjoyed the Special Olympics.

“He was a happy kid,” Joan Stover said while chatting in the family’s den, where some of Andy’s beloved Harry Potter books and toy monkeys were tucked on shelves. “He thought he was just hot stuff.”

The family had a mini-van with a ramp, and Andy loved to travel. Many scenes in the presentation at the service showed him at different local attractions and vacation spots, beaming a big smile.

“He went just about anywhere,” Doug Stover said. “We treated him just like anybody else.”

Wrenn said that Stover never made a fuss about the difficulties of having a disabled child. In fact, Wrenn said he didn’t know about Andy for a couple of years. But that, he noted, was reflective of Stover’s character.

“I never heard Doug complain about that stuff,” Wrenn said. “I tell you, that is one way to measure a man. He accepts what life gives to him and he moves on.”

During his tenure on the Outer Banks, Stover continued to break new ground, somehow seeing what others did not, or knowing ways to make things happen that others missed. Nearly everything having to do with history or culture on the Outer Banks came under Stover’s purview, and he was responsible for significant discoveries, improvements and restorations throughout the Outer Banks parks.

Some highlights: He helped get the first Underground Railroad site nomination in North Carolina; he ushered the Bodie Island Lighthouse and its Fresnel lens through its challenging four-year restoration; he worked on documenting records from the Hatteras Weather Bureau, including an original telegram sent from the Titanic; he discovered a scrapbook the Wright brothers kept of their 1908 flight in France, with their collection of newspaper clippings, as well as a program from 1928 in Kitty Hawk, signed by Orville Wright and Amelia Earhart; and he helped uncover original coastal survey markers at Whalebone Junction that turned out to be the only complete set in the US.

Three months after his park service retirement, Stover was working for UNESCO, due to his encounter with the king of Morocco, who had a connection to the organization. (It probably didn’t hurt that Stover had given the king a new WRV shirt.)

Stover still shows up at numerous meetings and events on the barrier islands, volunteers for as many as six nonprofit groups and frequently offers advice on historic preservation efforts.

“I’m still cleaning the Bodie Island Lighthouse lens every April,” he said.