If it seems like hurricanes in recent years are dumping more rain and causing more flooding when they make landfall, it’s because they are.

And according to two papers recently published in the science journal Nature, it’s all thanks to climate change and human activity. In some cases, cities themselves may be contributing to extreme rainfall.Supporter Spotlight

The first paper simulated how 15 historically destructive hurricanes across the globe would have developed in different scenarios: pre-industrial, modern and three potential late-21st century climates. It found that climate change increased the rainfall from hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria by 4-9 percent and could cause up to 30 percent more storm-derived rain in the future.

This comes as many parts of Eastern North Carolina are still recovering from Hurricane Florence – a storm that dumped a reported 9 trillion gallons of rain across the state and raised the bar for flooding in North Carolina.

And while Florence arrived too late to be included in this research, it’s conceivable to draw lines between the two.

Charles Konrad, director of the Southeast Regional Climate Center and a professor in the geography department at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, agreed. He explained that Florence’s size and slow forward momentum were big factors in the amount of rain that fell.

“There needs to be proper research done, but there’s the suggestion that the sea surface temperatures are warmer in that part of the Atlantic (where Florence traveled), and so we can certainly hypothesize that the rainfall rates were a bit greater with Florence – at least slightly greater – because with the ocean being warmer, there’s more evaporation and water vapor going up into the atmosphere,” Konrad said. “That’s something, if properly done, a climate attribution study might effectively show.”

Supporter Spotlight

Urbanization

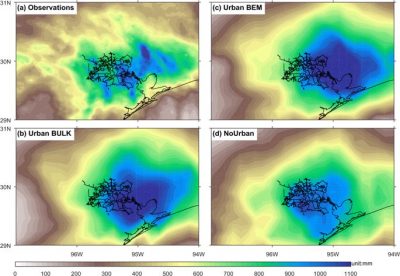

The second paper used data from Houston during Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and compared it to models of that area if the city had never been built. The conclusion was that “urbanization exacerbated not only the flood response, but also the storm total rainfall” and the probability of extreme flooding events was increased around 21 times, according to the paper.

Konrad explained that the tall buildings in Houston create a “surface roughness” that ends up putting more moisture into the air of a storm making landfall.

“When the winds carrying all this moisture hit these buildings, all of them together, you get more lifting and then that squeezes more rain out of the atmosphere,” he said. “It makes perfect sense.”

Sankar Arumugam, a professor and university faculty scholar at N.C. State’s Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering, has researched similar trends for the Southeast.

He said that while a slow-moving hurricane will almost always come with drenching rains, combining that with an urban setting that tends to trap air and moisture can help increase precipitation.

“We clearly see a trend in the tropical storm contribution in the precipitation,” he said.

To see if some of that moisture is going back into the air, rather than into nearby streams or creeks and rivers, or streamflow, he compared the records of rainfall amounts with that of streamflow measurements.

“What we find is that they do exhibit the trend in terms of increasing amounts of tropical storm contribution … but we don’t see a similar trend on the streamflow,” Arumugam said.

“The point is that perhaps – and this is not a conclusion – but perhaps the rural watersheds dampen that (rain) signal better as opposed to urban watersheds.”

Konrad said that as hurricanes or tropical storms make landfall, there’s always some additional “uplift” as onshore winds hit the land surface and any trees or buildings that may be on it.

“So it’s really a scale thing, right? Houston is a very large city and there’s been a tremendous amount of development and there are quite a few tall buildings,” Konrad said.

“But it’s intriguing to think that, yeah, with a lot of tall buildings – take Myrtle Beach, for example, where there’s just miles and miles of tall buildings – perhaps is increasing the rates of rainfall there locally when tropical systems are making landfall.”

‘A New Normal’

These papers could not show a link between climate change and its effect on the intensity of hurricanes, but the scientific community has agreed for decades that the trending impact of human activity on the climate will result in more frequent extreme weather events.

“We know meteorologically that as the world warms, there’s greater potential for higher rainfall rates,” Konrad said. “There’s also been work, too, that shows a really marked slowing down of hurricanes – not every single hurricane … but you’re getting more situations where they move really slow or stall out like we saw with Hurricane Florence. That’s something that connects with climate change.”

More severe extreme weather events are something we need to get used to, he said.

“We need to really understand that this is basically a new normal that’s developing here,” Konrad said.

“We’re seeing extreme precipitation and flooding occurring at a higher frequency than we’ve seen in the past inland … We need to really rethink what the 100-year flood is. We need to think about these events that, in the past, we would consider to happen once every thousand years – these are occurring more frequently. And we need to really think hard about how to get more people out of harm’s way.”