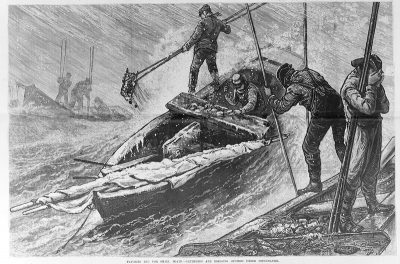

Late January 1891, the steamer Vesper, rented from the Wilmington Steamship Co. and mounted with a well-used howitzer and caisson borrowed from the state of Virginia, left Elizabeth City with militiamen of the Pasquotank Rifles. Their mission: To enforce “An Act to Promote and Protect the Oyster Interests of the State” that had been passed barely a week earlier.

After three years of growing tension between North Carolina oystermen and vessels drifting down from Chesapeake Bay to harvest oysters in Pamlico and Roanoke sounds, North Carolina’s legislature had acted, creating a list of draconian restrictions on the harvest that prohibited dredging and allowed only in-state residents to gather oysters.Supporter Spotlight

Tasked with telling the oyster poachers — mostly from Maryland — of the new law, as conflicts go, the North Carolina oyster war wasn’t much of a war, the rhetoric far outstripping the action.

“As she (the Vesper) proceeds on the return trip if any dredgers are found continuing to ravish the oyster beds they will be arrested, even if their boats have to be blown out of the water and their crews killed,” the Wilmington Weekly Star wrote.

In the end, the Vesper made one arrest, with other boats heeding the warning and leaving North Carolina waters.

Although short-lived and bloodless, what occurred on the water was but a part of an intersection of changing priorities in northeastern North Carolina.

The seeds of the war were sown 10 or 15 years before the first dredge boat appeared in North Carolina waters.

Supporter Spotlight

For decades, the Chesapeake Bay had been the center of United States oyster production, harvesting more than 20 million bushels at its peak in the mid-1880s.

But that production came at a cost. After surveying the oyster beds of Chesapeake Bay in the winter of 1879-80, Navy Lt. Frank Winslow observed, “I am of the opinion that though the fecundity of the beds in Tangier Sound is not yet destroyed, it is very much impaired, and that not only are the beds rapidly and surely deteriorating from the excessive fishery, but that their total failure, like unto that in Pocomoke Sound, is but a question of time.”

By the end of the 1880s, Winslow’s prediction had been borne out and the Chesapeake Bay harvest collapsed. The collapse presaged a far more violent and prolonged oyster war between Virginia and Maryland that included gunfire and death and was not fully resolved until the 1950s.

Yet if the harvest in the Chesapeake Bay had collapsed, the demand for oysters had not. Oysters had become big business. Though the bivalves were no longer available from Virginia and Maryland waters, the next nearest location where they were abundant were the sounds of North Carolina.

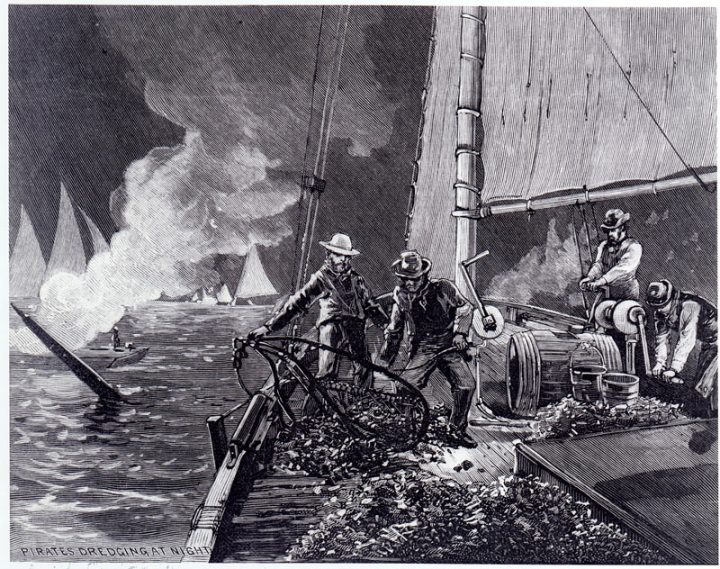

Until the northern oyster dredges arrived, the harvesting of oysters in North Carolina was a family affair with oystermen tending small oyster gardens near the shore, harvesting their oysters with tongs, a rake-like device with a hinged head to hold the shells in place. The technique was labor-intensive, and the depth of the water the oystermen could work was limited by the length of the handle.

Until the end of the 1880s there was no export market for North Carolina oysters, and the tongs and one-acre family oyster gardens were adequate to meet the state’s needs.

When the invaders arrived, mostly from Maryland, they brought with them the ability to dredge for oysters in the deepest and least-accessible reefs of the sounds, the capacity to work an area hundreds of acres in size and modern canning technology.

There is no record that the Vesper and its crew ever fired a shot in the North Carolina oyster war, but there were still battles fought, not with guns and bullets, but in the halls of power in Raleigh. The fishing interests of the state’s eastern counties held the protection of a way of life and its resource as a holy grail that could not be compromised; for the small cities and towns of the region, the canneries Baltimore industrialists had invested in represented jobs for North Carolina residents and tax revenues for the coffers of the towns and cities.

Writing in the Elizabeth City Weekly Economist the district’s state Sen. P.H. Morgan observed, “In Elizabeth City … a thriving, prosperous town … there are twelve canning and packing establishments, which employ during the oyster season seventeen hundred laborers and expend in aggregate $100,000 per month.”

The senator goes on to describe similar if smaller operations in New Bern and Washington, and notes that according to testimony before the Senate Committee on Fish and Fisheries that “… if the original bill passes that all these oyster industries in Elizabeth City and Washington must close and stop operations.”

“Should a law be adopted which would result so disastrously?” he asks.

From the second district that included Beaufort and Hyde counties, Sen. W.H. Lucas, according to the Washington Gazette, rose from his sickbed to address the Senate.

Acknowledging first that the House had passed the bill with, “… every member of that body living in the oyster section voting for it,” he went on to let the Senate know his position.

“Ah, some have tried to scare me on the other side. They have intimated: ‘Lucas you had better watch, you may never be returned again.’ Returned here again? Why, Senators, if I believe I’m right, and I know I am in this instance, if I never get another vote in my life I’ll vote for this bill … The welfare of those honest thousands is greater than the rise and fall of any living man.”

But the “Act to Promote and Protect the Oyster Interests” was never intended to be permanent law; rather it was viewed as a stopgap measure to protect North Carolina families who were harvesting oysters from the depredations of out-of-state interlopers. The law was successful in halting the influx of invading dredging boats but it also, as Sen. Morgan predicted, destroyed the oyster canneries of the region.

Within five years, dredging was once again allowed but restricted to North Carolina residents. By 1897 almost 5.8 million pounds of oyster meat were landed — about 35 times more than the state harvest in 2017.

That year, 1897, was the high point of North Carolina oyster production. A year later, the harvest had fallen off by 25 percent; within 10 years it was a third of the high mark.