MANTEO – The question of what happened to the 115 men, women and children of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island has endured in the American psyche for generations.

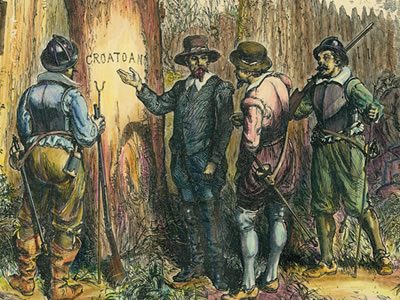

Established in 1587 and soon abandoned in a land of warring Native American tribes, short on supplies and lacking the skills needed to survive, the mystery of their fate has been unsolved since John White found the word “Croatoan” carved into a tree in 1590.

Supporter Spotlight

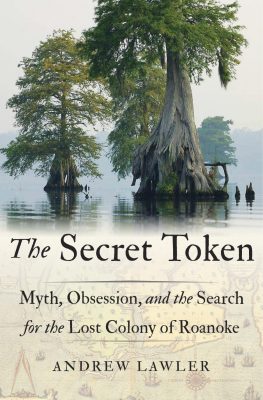

Using his perspective as a journalist and science writer, Andrew Lawler weaves a compelling and remarkable tale in “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.” Lawler is also the author of “Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization,” the story of how a semi-flightless Asian bird spread across the globe and become a source of food and power. As a journalist, his byline has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Smithsonian and others. He is a contributing writer for Science and contributing editor for Archaeology.

Lawler’s research bringing “The Secret Token” to life is astonishing, traipsing back and forth across the Atlantic to research original sources. Interviewing researchers, archaeologists, historians and the occasional quixotic theorists in his quest to discover what truly happened, he guides the reader on a journey of discovery, and he is a wide-eyed guide, as astonished at what he discovers as his tour group.

“I thought I knew the story when this all began,” he said.

The writing reflects Lawler’s journalism background. The sense of wonder comes in the sheer volume of information; the style though is objective and fact-based, and if there are conclusions to be drawn, it is because of the details that are presented in the book and not because of any opinion that he ventures.

Because he avoids expressing an opinion, as the facts build, “The Secret Token” seems, at times, like a mystery novel constructing a compelling case. Yet there is no smoking gun in this instance, saying “This is what happened.” What there is, rather, is the tapestry of the American experience as it has evolved over 400 years.

Supporter Spotlight

The search for the lost colonists becomes a reflection of the evolution of American thought.

“It was lost by us only in the 19th century,” he said, pointing to the first comprehensive history of this country, George Bancroft’s “A History of the United States.” The first three volumes of his 10-volume set were published in 1834 and covered the time from the first attempt at colonizing America to the Revolution.

Although Harvard-trained Bancroft had spent considerable time in Europe, especially Germany, at a time of rising romanticism in thought and a belief in myth to define an emerging German society.

“He cast it in those Gothic terms,” Lawler said

Seeped in the romantic writings of Europe, Bancroft wove a tale that fit the narrative.

“He called Virginia Dare the first English child born in the New World. He made her into a national symbol,” Lawler said.

That romanticized 19th century view of a white babe born among the “savages” still lingers. It can be seen even today in Paul Green’s “The Lost Colony,” the outdoor drama performed, in theory, upon the very land of the Lost Colony.

The play ends with the weakened yet determined colonists walking off into the wilderness, her father Anais dead at the hands of the savages, her mother holding the babe in her hands.

Green, though, was a radical in his day. During a period in U.S. history when miscegenation was illegal, especially in the South, his English settler Old Tom and native Agona marry, foretelling, perhaps what many archaeologists and historians feel eventually did happen.

“He (Green) supposed an assimilation there, with Old Tom and Agona marrying,” Lawler said.

Lawler does not just look at the influence of the Lost Colony on American thought, he also examines in detail the events that were occurring in Europe at the time.

What emerges is a place of political machination and intrigue. Spain, the dominant power of its time, pitted against England, an impoverished backwater land suspicious of science and innovation.

The detail is extraordinary but important in carrying the story forward.

In Green’s play the colonists are terrified of the Spanish. History demonstrates they were justified in their fear. On more than one occasion, all the inhabitants of a non-Spanish colony were put to the sword, and Roanoke Island was well within land Spain claimed.

The power struggle for control of the Americas and the seas played out in those 115 colonists. The colonists were seeking opportunity — a chance to better themselves economically and socially.

Whatever the game Raleigh, Queen Elizabeth and Simao Fernandes may have been playing is not as clear.

Fernandes, the pilot who insisted the colonists be deposited on Roanoke Island even though plans called for them to begin their life in the Chesapeake area, has always been suspect. But in Lawler’s nuanced examination of the man and the times his motivation does not seem nearly as sinister.

The modern characters who comprise the search for the Lost Colony may be the most fascinating. A remarkable conglomerate of scientists, quasi-scientists and crackpots fill the pages.

Lawler’s eye for detail in describing them is wonderful.

There is British archaeologist Mark Horton, who “… to the dismay of his dig team, refuses to wear a belt around his perpetually sagging trousers.” Nor does the man bathe as often as the people he is working with would wish.

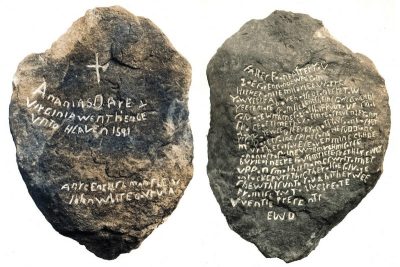

Fred Willard, who lived on the Outer Banks, was convinced the Dare Stone, a rock brought to light in the 1930s that seemed to tell the story of Virginia Dare’s demise, was real. He led his own excavations trying to find proof. “His bald pate, scraggly beard and piercing eyes gave him the look of a vengeful marsh prophet,” Lawler writes in describing him.

But the physical descriptions are the frame of a picture, a way to introduce the personalities. What emerges from Lawler’s interviews and observations are nuanced and complex characters who believe the quest for the truth will have an ending.

“The Secret Token” is a great read. It does not give a definitive answer to what happened to the Lost Colony. And in reading the book, the thought that there may not be a definitive answer seems likely. Yet what Lawler has done is expand the search for the inexplicable and unknowable into an examination of how we think of ourselves and our history.