Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

I recently found an historical account that I think might be the best description of tar making in North Carolina that I have ever read. An English merchant named Holles Bull Way wrote it in his travel diary when he visited coastal North Carolina in 1792. He did not publish those excerpts from his diary until 1809, though, when the article that I found appeared in the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, Great Britain’s first monthly scientific journal.

Supporter Spotlight

Way lived in Bridport Harbour, Dorsetshire. Now known as West Bay, it was a small town on the English Channel, at the mouth of the River Brit, and it’s main trades — rope making, net making and shipbuilding — all relied heavily on tar and pitch from North Carolina.

Tar, pitch, turpentine and rosin — all products made out of longleaf pine sap or wood — were collectively referred to as “naval stores.”

Way seems to have been a bit of a natural philosopher and inventor, as well as a merchant. When the price of North Carolina’s naval stores rose steeply soon after 1800, probably due to disruptions in shipping caused by the Napoleonic Wars, he turned his mind to the problem.

After all, the British navy and merchant fleet relied on that turpentine, tar and pitch to caulk the hulls of their ships, coat their hemp lines and preserve their decks, masts and spars.

I say all that because Way’s article wasn’t a travel story about an exotic destination: he was proposing a way for Great Britain to overcome its reliance on North Carolina’s naval stores.

Supporter Spotlight

Eyeing the rise in naval stores prices, Way hoped to persuade the esteemed fellows of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce to explore the feasibility of using the abundant groves of Scottish firs in the British Isles as the country’s source of naval stores.

For a number of reasons I won’t go into here, Way’s idea did not bear fruit and the U.S., and especially North Carolina, remained an indispensable supplier of naval stores to Great Britain at least until the American Civil War.

Fortunately for us, though, Way took the time in his article to familiarize the Journal’s readers with the processes of harvesting turpentine and making tar and pitch, based on a visit to North Carolina that he made in 1792.

In the article, Way actually quoted from the journal that he kept when he was in the Tar Heel State. It begins:

Thursday, April 12, 1792. Arrived at Wilmington, North Carolina, about 1 P.M. Observed on the roads the pitch-pines prepared for extracting turpentine; which is done by cutting a hollow in the tree about six inches from the ground, and then taking the bark off from a space of about eighteen inches above it, from the sappy wood.

“Pitch pines” today refers to a species of pine tree (Pinus rigida) that also has a high content of resin, or sap, in its wood and was historically used for the production of pitch, but Way was probably looking at longleaf pines (Pinus palustris), the more common source of pitch and other naval stores.

In the notes that he published in the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, Way concentrated above all on tar and pitch making. That was a little unusual. Many travelers in eastern N.C. in the 18th and 19th centuries commented on the naval stores industry, but they usually focused on the harvesting and distilling of turpentine, an at least somewhat more glamorous and profitable enterprise.

Way focused so fully on tar and pitch making that one has to wonder if he didn’t have a financial interest in those products when he visited North Carolina, or perhaps he was looking for new suppliers of tar and pitch for his business back home in Bridport Harbour.

While in North Carolina, I was particular in my inquiries respecting the making of tar and pitch, and I saw several tar-kilns.

He learned that Carolinians made tar and pitch with two different kinds of longleaf pine: most commonly, they used dead trees and fallen limbs, which they collected in the forest.

To a lesser extent, they used the “boxed” sections of the trunks of longleaf pines after they had been worked for several years and the resin, or turpentine, no longer flowed in them.

A “boxed tree” was one that had a section of its bark cut away so that the resin flowed into the hollow in the tree where it could be collected. To make “spirits of turpentine,” the woodsmen and women (often enslaved laborers) collected and distilled that resin, not terribly unlike making liquor.

According to Way, that tar produced from those boxed pine trunks was called “green tar,” having been made from green (unaged) wood instead of the dry (aged) wood from dead trees and fallen limbs.

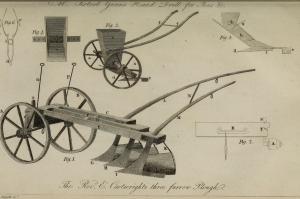

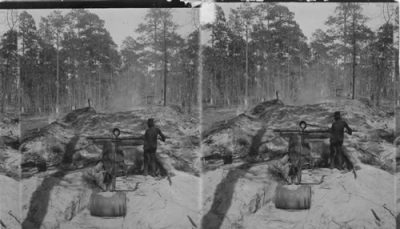

Way described the process of making the tar kiln in detail. The tar burners started by taking a string fixed to a stake in the ground and making a circle.

The size of the circle varied, but Way mentioned that tar makers generally said that a kiln 20 feet in diameter and 14 feet high would produce 200 barrels of tar, so perhaps that was a fairly typical size for a kiln.

As described by Way, they then dug a spade-deep hole that sloped downward to the circle’s center. Around the circle’s edges, they piled the earth until they had a low wall approximately a foot and a half high.

In the next step, the tar makers split a straight pine log and hollowed out both sides of the log. They positioned the log between the center of the circle and the outside, in a way that the end in the center was elevated higher. When the kiln was completed, the tar would run down the hollowed log into a hole dug outside the circle, where it was collected and put in barrels.

How the hollowed log didn’t burn, I don’t know. Later generations used metal piping.

The tar makers then filled the circle with split longleaf pinewood, piling it high and crowded tight.

After piling up the wood to a height of 12 or 14 feet, they laid “a parcel of small logs” over the top and then shoveled a thin layer of earth over those logs. They laid another layer of logs on the kiln, and then more earth, and so on, until they finished by encasing the whole construction with a thicker layer of earth.

Once the kiln was covered with dirt, the tar makers dug into it at 10 or 12 points and lit the wood on fire. The fire burned downwards, slowly smoldering and excreting tar for six or eight days.

In other historical sources, I have often read about the skill and artistry required of turpentine distillers, but Way’s account is the first I’ve seen that gives me a similar appreciation for the tar maker’s craft.

He wrote:

If it burns too fast they stop some of the holes, and if not fast enough they open others, all of which the tar-burner, from practice, is able to judge of. When it begins to run slow, if it is near where charcoal is wanted, they fill up all the holes, and watch it to prevent the fire breaking out any where till the whole is charred; the charcoal is worth two pence or three pence, British sterling, per bushel.

That is not very much, and in his article Way emphasized that tar burners did not grow rich from making charcoal or tar.

It will reasonably be supposed that tar burning in that country is but a bad trade, as it must be a good hand to make more than at the rate of a barrel a day…. the tar makers are in general very poor, except here and there one, that has an opportunity of making it near the water side.

By that last comment, Way meant that few tar burners had easy access to a creek or river and consequently had to spend a great deal of time transporting their barrels to a landing.

The Englishman concluded his discussion of North Carolina’s naval stores industry with the making of pitch, which is really just more refined tar. In Way’s day, pitch was widely used in shipbuilding for caulking and to waterproof the seams in barrels and kegs.

Way noted that the tar burners in North Carolina made pitch in one of two ways.

The first was by boiling the tar in a large kettle until it achieved the desired viscosity.

The other, rather more spectacular way was to dig another hole in the ground and line the hole with brick. They then poured tar into the hole and ignited it, allowing the tar to burn until it reached the right thickness. When it did, they covered the tar with earth to put out the fire.

To me Way’s account brings tar burning to life in a way that I had never seen before. And that is no small thing: turpentine and tar making were eastern North Carolina’s lifeblood for much of the 18th and early 19th centuries, much like tobacco and cotton would become later.

Across a vast territory, the land was mostly pine forest and those forests were full of boxed trees, tar kilns and tar burners, free and slave alike.

You can still find traces of tar making’s history when you explore eastern N.C. You can see them in dozens of old places names like Tar Landing, Pitch Kettle Creek, Tarkiln Neck, Tarboro and the Tar River.

You can find them, too, in the remnants of old tar kilns. They may not always recognize them, but every serious hiker, hunter and birdwatcher has seen them when they’re in the relatively upland parts of coastal N.C.’s forests.

Archaeologists have identified the remnants of more than 100 tar kilns just in the Croatan National Forest, south of New Bern.

Like Holles Bull Way’s words in 1792, those place names and old kilns remind us how important tar making was here and what the life of a tar burner and pitch maker was like in those long-ago days.