NORTHEASTERN N.C. – Not quite two years ago, the heavens opened over a sandy strand of land wedged between ocean and sound, drowning yards and roads and buildings – everything – in an epic deluge. In a span of three days in September 2016, more than 13 inches of rain fell on Ocean Sands, a subdivision on the northern edge of the Outer Banks in Corolla.

And that was before Hurricane Matthew blew through the next month and dumped another 18 inches. Hurricane Maria dumped more rain on the saturated ground last year. Not to mention Ernesto and Joaquin before then.

Supporter Spotlight

“I had crabs in my cul-de-sac,” said Linda Garczynski, recalling her Ocean Sands neighborhood during one storm.

But it’s not just the increase in monsoon-like rains in recent years that is challenging coastal areas in North Carolina. As water tables are getting higher and shorelines on both ocean and sound sides are eroding faster, tidal flooding is getting worse.

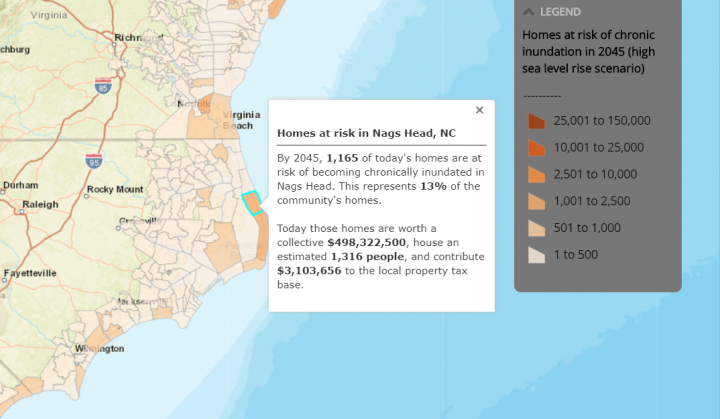

According to a report released this month by the Union of Concerned Scientists, by 2045 more than 15,000 properties in North Carolina, currently home to about 23,000 residents and valued at about $4 billion, are at risk of chronic inundation – that is, 26 or more times per year. Those properties, the report said, today contribute about $25 million in annual property tax revenue.

Accompanying the report online are interactive maps that show how many homes are at risk by state, community and ZIP code. The maps also show the current property value, estimated population, and the property tax base at risk.

In the lower 48 states, about 31,000 coastal homes with a market value totaling about $117.5 billion in today’s dollars will be subject to chronic flooding by 2045, the report said.

Supporter Spotlight

Thirty years from now, more than 700 commercial properties, today worth about $753 million, would also be plagued by frequent flooding, the report said. Valuable coastal property on the Outer Banks and northeastern North Carolina would be especially vulnerable, with about 2,000 homes combined in Nags Head and Hatteras at risk. Numerous communities with low wealth would have fewer resources to address the challenges. For instance, the overwhelming majority of homes in the tiny community of Alligator in Tyrrell County, one of the state’s poorest counties, would be exposed to frequent flooding.

The recent Union of Concerned Scientists report on the potential impact of sea level rise, using maps and data from, among others, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Zillow, a company that collects real estate data, is taking a deeper look into the potentially profound consequences of chronic tidal flooding impacts: increased property damage, loss of tax revenue, decreased property values, lower tax bases, flooded roads and bridges and dislocation of entire communities.

“We wanted to capture when sea level rise is going to cause such a disruption in people’s lives that they’ll make really dramatic changes,” said Erika Spanger-Siegfried, senior analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists’ climate and energy program.

Chronic tidal flooding, sometimes called nuisance flooding, is not new, but it’s starting to get more attention, especially in South Florida, she said.

In some places such as New Orleans and the Eastern Shore of Maryland, people have already made modest adjustments in their lives, such as having an alternate vehicle, one they don’t mind exposing to saltwater, to use on flooded days.

The goal of the report is to encourage communities to start talking about flooding before it becomes a constant crisis, Spanger-Siegfried said.

“This is not something an individual, or frankly a community, can cope with alone,” she said. “The critical thing is we need to know our risks and start to do things … in the time that we have before chronic flooding is really upon us.”

There are choices, depending on the degree of risk, that include the following:

- Defend – bulkheads, levies, living shorelines, beach nourishment, sea walls.

- Accommodate – buildings on pilings, bridged areas, no living quarters on ground floors.

- Retreat – relocate out of flood zones, move to higher ground or leave the area altogether.

“It gets hard when it comes to specifics, because each community is different,” she said. “That’s another reason to start to get a handle on the problem and begin to get ahead of the situation.”

In the process of gathering feedback earlier this year about stormwater flooding in Currituck County, Duke University graduate student Amber Halstead for her master’s thesis found that people’s perception of flooding risks correlates with their experience with flooding much more than the designation on flood maps. Although most people she spoke with recognize the value of flood insurance, she said some say they will drop flood insurance when the new flood maps go into effect because of the high cost.

In a recent telephone interview, Halstead said that about 500 people responded to an online survey and she spoke to others at several community meetings held throughout the county this past winter.

“I do think the majority of respondents do think the flooding is getting worse,” she said. “I don’t think they had specific solutions. They just know that something needed to happen.”

At Ocean Sands, the bowl-like typography of the neighborhood makes it even more subject to flooding than others in the barrier island community. But the challenge is not just that the deluges seem to be more frequent and intense. It’s also that there are more impermeable surfaces and the water table is higher.

Ocean Sands, one of the oldest subdivisions in Corolla, is working with the county and an engineering firm to develop a long-term storm management plan.

“There’s a lot of construction, a lot of cement,” said Larry Landrum, an Ocean Sands homeowner. It’s the over-building. Everybody wants to live on the Outer Banks.”

Front page featured photo of the oceanfront in Nags Head after Hurricane Matthew turned offshore, Oct. 9, 2016, by Catherine Kozak.