CARTERET COUNTY – If someone named an environmental all-star team in Carteret County, 66-year-old Michael Murdoch of Wildwood and Ocean would surely be a unanimous choice.

He cofounded the Croatan group of the Sierra Club a few years ago, and has watched its membership double. If there’s a public meeting or a rally, he’s there, pushing to stop oil and gas drilling off the North Carolina coast and to promote wind and solar.

Supporter Spotlight

He’s organizing a big campaign to address roadside and waterborne litter in the county. He’s trying to stop the state Department of Transportation from building a four-lane highway through Wildwood. And, in his “spare time,” he is building a solar-powered barn on his all-natural, all-organic small farm in Ocean.

If you get Murdoch talking about that, you might think he thinks it’s the most important thing he is doing. In truth, though, he sees the 5-acre farm as a natural extension of all the other work he does, a demonstration of an unwavering commitment to not just talk the environmental talk, but to walk it.

He and his wife, Deede Miller, sister of North Carolina Coastal Federation founder and director Todd Miller, bought the land from Todd’s father, Teddy, about 10 years ago.

He’s grows lots of things – tomatoes, asparagus, blueberries, okra, sweet potatoes and of course, the world-famous Bogue Sound watermelon. He gives away a lot of what he grows, and sells enough to more or less break even.

“I wouldn’t call myself a farmer,” he said on Sunday morning as the wind rose off nearby Bogue Sound. “I’m more of large-scale gardener. And it’s not really a business.”

Supporter Spotlight

It’s really a concept, and a labor of love. He mixes rotted sawdust with soil, buys manure for fertilizer and even has a solar-powered electric fence to keep the deer out.

And the barn/shed? He and a friend are building it by hand, slowly, with recycled lumber. It will be solar-powered, too. Inside are two tractors, dating back to 1940 and 1949. Both work.

“There’s no electricity here,” he said. The downstairs is mostly Murdoch’s work space, while the upstairs is Deede’s art studio. Besides, Mr. Murdoch wants to set an example for others to show that it can be done. He knows there are all-natural farms elsewhere, but knows of no others around here.

“Some of my friends laugh at me, but what else am I going to do with my time?” he said.

Murdoch grew up in Wildwood, then a largely rural community west of Morehead City. It was an idyllic time, in the 1950s and ’60s, before the boom along the coast, and Murdoch recalls fondly walking with his dad in the woods to go fishing or “just to be outside.” Life pretty much revolved around the Presbyterian church.

His mother was employed at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s fisheries lab on Pivers Island in Beaufort, so science and education were important to the family.

After graduating from West Carteret High School, Murdoch went off to East Carolina University to major in parks management. The environmental movement was just kicking into gear; folks were reading Rachel Carson’s seminal “Silent Spring” and Aldo Leopold’s “Sand County Almanac.” Murdoch attended his first Earth Day event at ECU. It struck a chord that still reverberates today.

It was also a time of gasoline lines. People believed the world was running out of oil. It was really just the Arab oil embargo that caused the lines, but it got many people, including Murdoch, thinking of a world in which fossil fuels wouldn’t be the dominant form of energy. Since then, a majority of the American public has come to believe that fossil fuels are causing climate change.

“I would say it was a turning point for me, like it was for a lot of other people, when Earth Day started,” he said. “There was so much energy and enthusiasm, and you just wanted to be involved.”

Murdoch earned his master’s in recreation and parks administration from Clemson University, and his professional career took him to parks in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia and Maryland.

In South Carolina, he got his first experience with starting a Sierra Club Group in Georgetown.

He met Deede Miller, from Ocean, at his 20th high school reunion at West Carteret.

“I’d never been to one before,” he said. “My mother made me go. It was right time, right place.” They married in 1990. But Murdoch always knew that when he retired, he wanted to come home to Wildwood. Miller wanted to come back, too.

“There’s just something about this county,” he said. “There are plenty of great places to live, but Carteret and its people get a hold on you.”

So in 2012, back they came. Wildwood was still much the same at its core; a quiet rural place with lots of farms and woods. But the post office is gone, the volunteer fire department is gone, and around the edges, Morehead has been steadily approaching with shopping centers and developments, many of them paving farm fields, causing more runoff into the Newport River. But the changes in the past couple of decades, Murdoch believes, are nothing compared to what might come.

Near the end of 2017, DOT began planning for a road project long pushed for by Morehead City and county officials, that will cut through the Wildwood community, but residents have pushed back in opposition to the plan, urging the state to find another route.

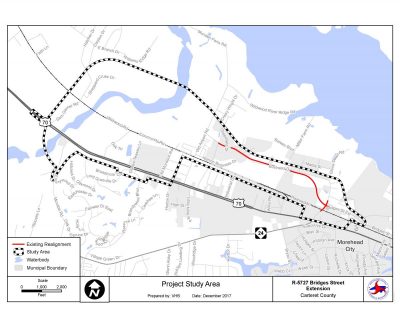

The proposed $44.2 million project is included in the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) as project R-5727. It would extend the current Bridges Street Extension by about 3 miles and connect Morehead City and Newport.

The road project includes widening the roadway along Business Drive to Old Airport Road and will continue westward to connect to U.S. 70 near McCabe Road. It would be a four-lane, 120-foot thoroughfare divided by a raised median and will run essentially parallel to U.S. 70.

“It would destroy Wildwood,” Murdoch said. “DOT says it’s to get people off Highway 70, but for what purpose? To get people from one place another a couple of minutes faster? And at what cost? The destruction of a community?”

DOT, he said, has talked about improving things for motorists, “what about our quality of life? We matter.”

So Murdoch and others started a petition drive, and he believes they’ve gotten DOT’s attention. But the outcome is far from certain, and Murdoch believes the process was flawed to begin with.

The justification for the project appears to come from a survey distributed in 2011.

But, he said the survey “asked the respondents where they lived,” but Wildwood wasn’t even listed as an option.

“Was this intentional or just an oversight? Apparently Wildwood is not considered a community anymore. Wildwood was left off the survey despite having its own voting precinct.”

At any rate, Murdoch has been impressed by the volume of support he and others have received.

“It’s made me very optimistic,” he said. “I didn’t think we’d get this much support. At least they (DOT) now knows Wildwood exists. I get the feeling that some planner just looked at a map and say, ‘Hey, there’s nothing here’ and drew a line through Wildwood. Well, we are here, and care.”

Murdoch started the Croatan chapter with help from others and in just a handful of years, with him as chairman, it’s grown from about 300 members to more than 600, and the club has become prominent in the fight to keep oil and gas drilling away from the North Carolina offshore waters. The club serves Carteret, Craven, Jones, Onslow and Pamlico counties, and has organized and conducted numerous waterway and shoreline cleanups.

Which brings us to … litter, the most recent of Murdoch’s passionate causes.

He maintains that it increased in recent years, while cleanup efforts and police citations for littering have declined, as have convictions.

“I know there are obviously more important things, like murder and opioids, but this litter – much of it plastic – is choking us.”

In the old days, Murdoch said, most people thought of litter as just an eyesore. But new research increasingly shows that in the water, plastics break down into micro-plastics, which are consumed by marine organisms and then consumed by us.

“I think we need a unified approach,” he said. “We’ve got to make sure people understand that it’s more than just an ‘eyesore’ problem.”

Murdoch has been meeting with community leaders and politicians and candidates, as well as the Carteret County Chamber of Commerce and law enforcement agencies in order to get an initiative started in April.

He’s not sure yet what form that initiative will take, but knows it should include strong cleanup components as well as public education.

“I think it’s just a forgotten issue. When was the last time you saw one those ‘$50 fine’ signs to warn people about littering?” Murdoch said.

“It used to be people thought most of the litter came from tourists,” he said. “It’s now pretty obvious that many people are part of the problem, and many people need to be part of the solution.”