At the turn of the 18th century, there was no love lost between the North Carolina and Virginia colonies.

Blackbeard was the scourge of the seas, and although he operated in North Carolina waters, somehow North Carolina authorities could never lay their hands on him. The enmity was exasperated in 1718 when Virginia Gov. Alexander Spotswood dispatched the Royal Navy to deal with the problem.

Supporter Spotlight

When Lt. Robert Maynard returned to Hampton Roads with the pirate’s head on a spit, he also had a letter from Tobias Knight, secretary of the North Carolina colony, warning Blackbeard the British fleet was coming.

At the request of Spotswood, Knight was tried by the North Carolina General Assembly, which found him innocent of all charges.

However, the issues paled in comparison to the lack of a clear border between the colonies. For colonies intent upon growing their populations and tax base, a well-established border was an imperative.

The only documentation recording the border, though, was the 1663 Lords Proprietors’ royal charter describing the border as, “To run from the North End of Corotuck-Inlet, due West to Weyanoke Creek, lying within or about the Degree of Thirty-Six and Thirty Minutes of Northern Latitude, and from thence West, in a direct Line, as far as the South-Sea.”

Corotuck-Inlet, or Currituck Inlet, had migrated. More confusing, however, was Weyanoke Creek—50 years after the document was created, no one knew of any creek named Weyanoke.

Supporter Spotlight

In 1710, the colonies cooperated in conducting a border survey, but poor equipment, poor leadership and general incompetence doomed the attempt. Hoping for a permanent solution, Govs. Charles Eden of North Carolina and Spotswood agreed to a 15-mile buffer zone where no settlers were allowed. Virginia seems to have abided by the agreement; North Carolina did not appear to be as strict about enforcing the prohibition.

In 1728, at the urging of England, another effort was made to establish the borders. Leading the North Carolina contingent was Edward Mostly, who had led the flawed 1710 expedition. The Virginia group was led by William Byrd II.

A prolific diarist, writer and wealthy landowner, Byrd produced two books recounting the expedition. Neither book was published during his lifetime.

His “Dividing Line Run in the Year 1728” would have been the official account of the expedition and his observations of the environment and day-to-day existence are remarkable in their clarity.

But for the real story behind the expedition, “A Secret History of the Dividing Line” is filled with details of life in northeastern North Carolina, sexual indiscretions and strife among the members.

Assigning pseudonyms to the members, Byrd, who gave himself the name Steddy, holds nothing back.

His disdain for North Carolina is clear from the opening pages. When a letter arrives from the North Carolina contingent undated, he comments, “This Letter was without date they having no Ahnanacks in North Carolina …”

The arguments began on the first day. The instructions were to use the Lords Proprietors’ charter as a starting point, but it was apparent the “North End of Corotuck-Inlet …” had shifted dramatically over the years.

“We had a tough dispute where we shou’d begin: whether at the Point of high Land, or at the End of the Spit of Sand, which we with good reason maintain’d to be the North Shoar of Coratuck Inlet … This Controversy lasted til Night neither Side receding from its Opinion,” Byrd wrote.

Some arm twisting by Steddy convinced Plausible, or Edward Moseley, that if they didn’t resolve it, Moseley would be blamed.

The survey took the teams back and forth across the border, and Byrd’s disdain for North Carolina seems to grow as the survey continues. He finds its residents’ diet particularly objectionable.

“The Truth of it is, these People live so much upon Swine’s flesh, that it don’t only encline them to the Yaws, & consequently to the downfall of their Noses, but makes them likewise extremely hoggish in their Temper, & many of them seem to Grunt rather than Speak in their ordinary conversation.”

The Yaws is a disease whose primary symptoms are boils.

Throughout his “Secret History,” Byrd points to the laziness of the North Carolina population.

“The Distemper of Laziness seizes the Men oftener much than the Women. These last Spin, weave and knit … while their Husbands, depending on the Bounty of the Climate, are Sloathful in every thing but getting of Children, and in that only Instance make themselves useful Members of an Infant-Colony.”

It was not just dietary habits that drew Byrd’s ire.

As the surveyors worked their way west, they would often stay with property owners along the border. At Princess Anne, just north of Knott’s Island they stayed with Willoughby Merchant, Justice of Princess Anne. Byrd chose to camp in the pasture with some of the workers who were helping the commissioners.

Other commissioners, North Carolina and Virginia, decided to stay at the house.

“But it seems they broke the Rules of Hospitality, by several gross Freedoms they offer’d to take with our Landlord’s Sister. She was indeed a pretty Girl, and therefore it was prudent to send her out of harm’s Way. I was the more concem’d at this unhandsome Behaviour, because the People were extremely Civil to us, & deserv’d a better Treatment.”

For good reason the passages disparaging North Carolina and its residents and recording the various attempts at amorous adventures of his fellow travelers are the most compelling reading, but Byrd also writes with a keen eye for the environment and 18th century culture.

The survey teams made good progress until they reached the Great Dismal Swamp. The going was difficult, but the teams kept going, delineating the border link by survey link.

“The reeds which grew about 12’ high, were so thick, & so interlaced with Bamboe-Briars, that our Pioneers were forc’t to open a Passage. The Ground, if I may properly call it so, was so Spungy, that the Prints of our Feet were instantly fill’d with Water. Amongst the Reeds here & there stood a white Cedar, commonly mistaken for Juniper.”

It was also at the edge of the Dismal Swamp that Byrd encounters a feature of slavery.

In his more official account, Byrd writes, “There we came upon a Family of Mulattoes, that call’d themselvs free, tho’ by the Shyness of the Master of the House, who took care to keep least in Sight, their Freedom seem’d a little Doubtful.”

If, however, the Secret History is the true story, the encounter takes on different tone. Describing the woman as a “Dark Angel,” Byrd writes, “Her Complexion was a deep Copper, so that her fine Shape & regular Features made her appear like a Statue en Bronze done by a masterly hand. Shoebrush (a member of the North Carolina party) was smitten at the first Glance, and examined all her neat Proportions with a critical Exactness. She struggled just enough to make her Admirer more eager, so that if I had not been there, he wou’d have been in Danger of carrying his Joke a little too far.”

There are also some interesting snippets of information. As the team sends the preacher and one of the commissioners off to minister to the “infidels” of Edenton, rum is sent with them.

“Most of the Rum they get in this Country comes from New England, and is so bad and unwholesome, that it is not improperly call’d ‘Kill-Devil,’” Byrd writes.

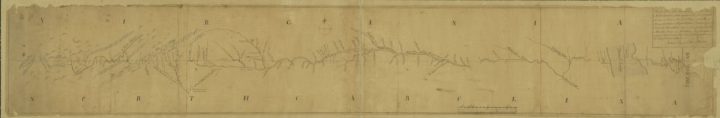

Despite the tensions that existed among the delegations, the survey was successful. In March and April, the surveyors established 73 miles of border. Not wanting to brave the summer heat, they waited until fall to continue and pushed the border markers out another 100 miles.

At that point, abiding by their instruction from the colony, the North Carolina delegation said they were returning home.

“I let them know it was a little unkind … to have inform’d us with their Intentions before we sat out, how far they intended to go that we might also have receiv’d the Commands of our Government in that Matter. But since they had failed in that civility we wou’d go on without them …” Byrd wrote.

The Virginia surveyors continued for another 64 miles, reaching the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

The boundary marked by the 1728 expedition is, with minor corrections, the border between the states as it exists today.