COLUMBIA — For the time being, it might be best to ignore the little sign off U.S. 64 in Tyrrell County directing drivers toward the Palmetto-Peartree Preserve. Years of neglect have left roads into the densely vegetated land nearly impassable and boardwalks subsumed by overgrown plants.

But better days may be ahead for the 10,297-acre site, which is in the process of being transferred to the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Supporter Spotlight

“What we want is the promises to be fulfilled,” said David Clegg, Tyrrell County manager. “First and foremost, for infrastructure within that tract to remain open and accessible so it would fit our vision of ecotourism.”

Created in 1999 by the nonprofit organization, The Conservation Fund, as a mitigation bank for the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker, the PPP, or alternately, P3 — the preserve’s informal names — fell into disrepair after its ownership was transferred in July 2015 to the state Department of Transportation, which had neither funds for nor interest in the preserve’s upkeep.

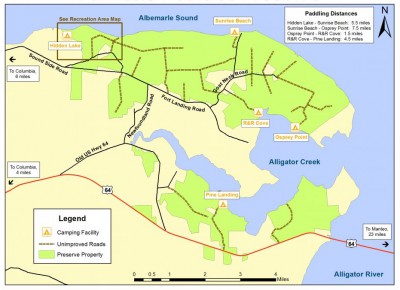

The former pine and hardwood timberland, bordered by the Albemarle Sound and the Little Alligator River, turned out to be good habitat for the woodpeckers. For that reason, NCDOT ended up managing the species at the preserve to mitigate the bird’s habitat loss at its construction sites elsewhere in the state.

The woodpeckers were listed as endangered in 1970. Considering that the birds take about nine years to excavate a cavity in a 100-year-old loblolly pine tree — or as long as 13 years in a longleaf pine — it’s a wonder the species has survived at all.

But the hard-working birds can get lucky and inherit a cavity from their relatives, which would free them up to spend their time defending the cavity from numerous interlopers. Though, climate change may end up being the woodpeckers’ doom at the preserve: rising water tables in the preserve are slowly killing the pines that the birds require for their chosen cavities.

Supporter Spotlight

DOT has mostly met its conservation requirements at the preserve, and has long been looking to transfer it to a willing recipient. The Conservation Fund had intended to keep the site no longer than five years, but no agency or nonprofit came forward, leaving the preserve in DOT’s hands by default.

“The mitigation need for that property is no longer necessary,” said Brent Wilson, the wildlife commission’s coastal ecoregion supervisor.

The commission approved the acquisition at its Oct. 5 meeting. The state property office, he added, is working on the deed and a memorandum of understanding that will retain some rights for the donor DOT to conduct any necessary mitigation or road work in the future. The transfer is expected to be finalized by the end of April, he said, and the boundaries posted by Sept. 1 to delineate from private lands.

“The Conservation Fund is very pleased that the property is going to be transferred,” said Bill Holman, the fund’s state director in North Carolina. “We think the Wildlife Resources Commission will do a good job managing the property and opening it up to the public.”

In 2015, there were about 32 clusters used by the birds at the preserve. A cluster is an aggregation of cavity trees used by a family group. An environmental consultant company had managed the species for DOT since 1995.

Wilson said that acquisition of the preserve would expand the bear hunting opportunities in the region, as well as recreational activities for kayakers, hikers, bicyclists and birdwatchers. Squirrel and deer hunting also would be likely permitted.

The tract is located near the 14,178-acre Alligator River Game Lands, the 1,441-acre Texas Plantation Game Land waterfowl impoundments and the 2,100-acre J. Morgan Futch Game Land, all also managed by the wildlife commission.

Back when The Conservation Trust owned the property, it had constructed boardwalks, trails, launch areas for kayaks and canoes, birdwatching overlooks and a camping platform in Hidden Lake. But all of that infrastructure is now in disrepair.

The preserve, which was named after shoreline land forms Palmetto Point and Peartree Point, had a portion of it leased to hunt clubs — its heavily vegetated wetland swamps and pocosin forest are thick with bear. The intention was to promote the area as an eco-tourism destination, but over time the plans fizzled out. Guides have continued to take groups out to the site during the annual Wings over Water birdwatching event, and hunters still trudge through the thickets, but the preserve is too rugged and rough going for the casual recreational visitor.

According to a commission document, the preserve has more than 23 miles of unimproved logging roads that had been maintained to conduct monitoring of the woodpeckers. But roads will not be able to support traffic from hunters without a gravel surface, the document said, and new gates would need to be installed on roads. Road upkeep is projected to be the preserve’s largest management cost.

Wilson said that the commission did not appropriate any funds specifically to upgrade the preserve’s infrastructure, but he expects that improvements will be made as much as current funding allows. But a partnering arrangement could also benefit the preserve.

Tyrrell County would “certainly” be interested in a partnership with the state, Clegg said, including looking for grant funds.

Not only do the roads need to be fixed, he said, the public accessibility overall needs to be improved with trail maintenance and drainage restoration.

“There’s remarkable opportunity for birding back there that people would love to visit,” Clegg said. With some clearing and repairing and updating, the site would be attractive to people who love being among wild, pristine nature.

The preserve is situated on the outskirts of Alligator and Fort Landing adjacent to the Goat Neck community, a rural area where people have lived for generations.

With 53 percent of its 700 square miles in public hands, Clegg said, the county needs the revenue that eco-tourism can provide. As a result, government agencies that manage the refuges, preserves and game lands should not be surprised that the county is pushing them for some help.

“You just can’t keep taking and taking and taking without being a partner who helps create the quality of life that supports existence of these natural areas,” Clegg said. “Bear hunting is very important to this county, but so are children going to school.”

Only 3,665 people live in Tyrrell County — it’s often said that it has more bears than people — and the average annual wage is $29,000, the state’s lowest. Working people may be poor, Clegg said, but they make enough to live in the county and no one is looking for a hand out.

“ ‘Oh woe is me’ — that’s not happening here,” Clegg said.

Eco-tourism is the best option for the county to bring in more money, but it will require building places for visitors to eat and to stay.

“Wildlife is ubiquitous in Tyrrell County,” he said. “We’ve just got to be able to capitalize on that and we need the refuges and preserves to help.”