About two and a half miles north of Portsmouth Island, Shell Castle Island barely manages to rise above the waters of Pamlico Sound. Now owned by the Audubon Society, except for some nesting seabirds, there isn’t much there. The Cedar Island Ferry passes close by, taking advantage of Wallace Channel.

Wallace Channel, named for one of the island’s early owners, may be the last reminder of a time when that patch of sand was the center of maritime trade for northeastern North Carolina and the remarkable role it played in the early history of the United States.

Supporter Spotlight

Little evidence remains of the entrepôt, the distribution and storage facility in the middle of Ocracoke Inlet. On very rare occasions, a creamware pitcher with a transfer print of Shell Castle Island in its heyday will be found. As far as anyone knows, it is the only visual representation of “Governor” John Wallace’s domain.

John Wallace was never an elected official, and was certainly not the governor of North Carolina. He was a ship’s pilot sailing from Portsmouth Village, and it would seem a very good one. That skill is what brought him to the attention of John Blount, a wealthy and powerful North Carolina merchant and businessman.

Blount and his brothers, Thomas and William, operated a mercantile business in the port city of Washington on the Tar River. Opened in 1783, business was booming as trade flowed into the newly formed Untied States of America.

Washington, 80 miles east on a straight line from Ocracoke Inlet, had become one of the busiest ports in the state. Wilmington, with its deep water, serviced the southern part of the state, but the coastal towns of northeastern North Carolina could only be reached by crossing the sounds behind the Outer Banks, and the only way into the sounds was through Ocracoke Inlet.

The inlet, however, was difficult to navigate with a shifting bar and uncertain channels. After crossing the bar, most oceangoing ships had too deep a draft for the shallow waters of the sounds and had to be lightered, or off-loaded, onto smaller ships designed for the Inner Banks. Lightering and piloting services were provided from Portsmouth Village or Ocracoke.

Supporter Spotlight

Despite more than 100 years of experience piloting and lightering ships, there wasn’t much to recommend Ocracoke Inlet or the two villages connected to it.

“Other than piloting and fishing the only business operating at Ocracoke following the Revolution was a tavern at Portsmouth,” Phillip McGuinn wrote in an unpublished master’s thesis on Shell Castle Island on file at East Carolina University.

After the American Revolution, the Blount brothers moved quickly to establish a trading and business network that spanned the Atlantic Ocean.

“By the 1790s the Blounts managed a far-flung business, trade, and land speculation empire whose spokes radiated out from North Carolina to western lands in Tennessee and Alabama and trade networks reaching Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, and Charleston; the Danish, Dutch, French, and British islands in the West Indies; and Europe,” David and Anne Whisnant wrote in a study prepared for the National Park Service.

The center of those spokes was Washington, in Beaufort County, and if there was a weak link, it was the lack of facilities as ships crossed the Ocracoke bar.

Blount, with help from Wallace, was determined to change that.

In 1789, Blount and Wallace purchased a group of oyster beds called Old Rock, changed the name to Shell Castle Island and began bringing ballast and construction materials to the island.

Within a year, the Shell Castle Island was operational. Construction would continue for the next 17 years. Wharfs, a warehouse, tavern, grist mill and homes were built on the island that would eventually be 60 feet across and a half-mile long.

The choice of Shell Castle as the base of their enterprise was not accidental.

“‘Shell Castle,’ lay on the north side of Wallace’s Channel, at the middle of the inlet, strategically placed in deeper water between the inlet’s two main navigable channels, Wallace’s Channel and Ship’s Channel,” the Whisnants noted.

Wallace, as the onsite manager of operations, lived on the island with his family and ruled his small empire as “the Governor.” As the operation expanded, the population of the island would eventually grow to 45, including slaves, most of whom were owned by Wallace.

Simply creating the entrepôt would not bring ships to Shell Castle. To insure the success of their enterprise, the partners created a surprisingly sophisticated marketing strategy.

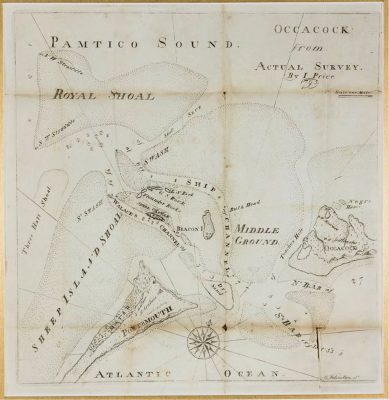

Recognizing the concerns that ship’s captains had about Ocracoke Inlet, they commissioned North Carolina cartographer Jonathan Price to create a map. The eight-page pamphlet and map has the distinction of being the first map published in the state.

The title was long and descriptive. “A description of Occacock Inlet: and of its coasts, islands, shoals, and anchorages, with the courses and distances to and from the most remarkable places, and directions to sail over the bar and thro’ the channels adorned with a map, taken by actual survey, by Jonathan Price.” The map, and instructions on how to navigate the bar, were remarkably accurate.

Included in the pamphlet is a description of Shell Castle Island accommodations. “…(a) dwelling-house and its out-houses, which are commodious, here are ware-houses for a large quantity of produce and merchandize, a lumber yard and a wharf, along side of which a number of vessels are constantly riding. These late improvements contribute much to the usefulness of the establishment, and give it the appearance of a trading factory …”

The creamware vase with the rendering of Shell Castle also seems to have been a part of the marketing outreach of Blount and Wallace.

Sometime around 1800, the partners had a drawing commissioned of the island and had the rendering sent to England to be transferred onto a pitcher. The transfer method for placing the image on the pottery was first developed in Liverpool and the style is called Liverpool Ware although the pitcher could have been made almost anywhere in England.

Written on the rendering is a description of what is seen.

“A north View of Gov.r WALLACES Shell Castle & Harbour NORTH CAROLINA.”

In explaining what the pitcher represents, McGuinn suggests it was a way to remind their more important clients of Shell Castle Island.

“… the jugs most probably represents another marketing tool used by Wallace and Blount to promote the importance of the place. The pitchers were probably used as gifts to family friends and extremely close business associates,” he wrote.

The rendering is not completely accurate. Depicting a lighthouse on the right side of the image, the tower seems to be almost a part of Shell Castle.

The actual lighthouse was on Beacon Island, also owned by Blount and Wallace, a mile and a half to the east of Shell Castle.

The partners had hoped to place a lighthouse on their entrepôt island, and exerted considerable pressure to do so. The nascent federal government originally planned on building a lighthouse at Ocracoke, but a concerted lobbying effort involving a letter-writing campaign from ships’ captains and using Shell Castle and the political arm twisting of John’s brother, U.S. Rep. Thomas Blount moved the location.

However, for reasons unknown, the state of North Carolina failed to give a grant ceding the land to the federal government, granting instead Beacon Island. The contract however, called for construction on Shell Castle Island. The lack of facilities and the need to bring in considerable ballast to protect the site resulted in cost overruns, as the contractor, Henry Dearborn, wrote to President Jefferson in 1803.

“It had been understood by Congress at the time the act passed authorising the erection of those lights, and by the Executive & myself at the time the contract was made, that what was called Shell Castle Island, was really an Island, and all the enquiries I made … but I since found that Beacon Island which is about two miles from shell castle, and which had been purchased by the United States for the purpose of erecting a fortification …”

The light atop the wooden tower was illuminated in October 1803, nine years after congressional action to construct a lighthouse marking Ocracoke Inlet. The Shell Castle Island lighthouse was struck by lightning and destroyed in 1818.

The lighthouse was never replaced, the Ocracoke Lighthouse taking its place.

By the time the lighthouse on Beacon Island had burned to the ground, Shell Castle was well into decline. The channels that had made it so well-positioned had shifted. The War of 1812 destroyed U.S. shipping interests as British ships blockaded ports of entry.

The most devastating blow though was the death of the Governor, John Wallace, in 1810. Somewhat erratic in his management style and terrible at recordkeeping, he was, nonetheless, the driving force that kept Shell Castle Island viable.

Perhaps the last government record of Shell Castle Island came in 1835 when a request was forwarded to the Treasury Department for funds to lease the Island for the storage of naval supplies.