Rick Luettich, director of the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, grew up in Maine, fascinated by water. But it was very cold water.

“I’m not sure why it fascinated me,” he said. “We had ponds and creeks and snow melts, and I just loved to be out in it, building dams and playing and figuring things out. I remember always coming into the house soaking wet as a kid, and getting told by my parents that maybe I ought to spend a little less time in it. And it really was cold.”

Supporter Spotlight

It’s no surprise, then, that when the self-professed lifelong science and math geek went off to college, he chose a warmer clime, Georgia Institute of Technology, otherwise known as Georgia Tech, in Atlanta, where he earned his civil engineering undergraduate and master’s degrees, before returning to New England to earn his doctorate in civil engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT. Cold water again.

So what to do after graduation? Having had a taste of the South, New Englander and Boston Red Sox fan Luettich eventually went back to it, and started work in 1987 as an assistant professor in marine sciences at UNC-IMS. Warmer water, for sure, but it still fascinated him, though mostly, now, it contained fish and shellfish. That, after all, was the primary focus of the institute, and still is.

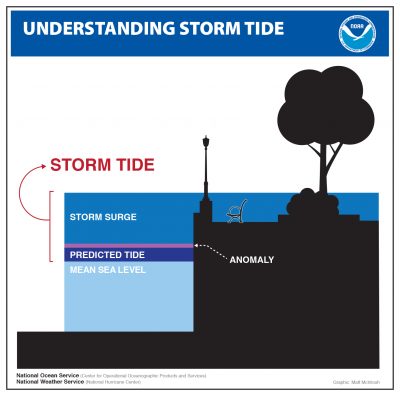

His research for a time focused mostly on how the movement and the quality of water affected marine life. But he’s also always been interested in the practical application of his scientific research. Eventually, that led him to be the co-developer of ADCRIC, a computer modeling program that over the past 20 years has become the most-used method of predicting how much storm surge will affect particular locations as hurricanes approach land.

He hasn’t given up his other research and work, such as observational studies that have included moored and shipboard sampling to characterize physical processes in coastal systems, often oriented toward understanding the role of physical processes – algal blooms, dissolved oxygen depletion – in areas of water quality and fisheries recruitment.

But he’s been a busy man this fall, as hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria approached Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, respectively, pushing storm surges measuring in feet into some heavily populated and vulnerable areas.

Supporter Spotlight

Luettich might not be The Weather Channel’s Jim Cantore, ubiquitous in rain gear, showing up wherever a hurricane is poised to strike. But he’s become somewhat of a media star nevertheless, turning up to discuss potentially deadly storm surges. He’s done a couple of dozen interviews this hurricane season, and he’s glad to do it, because he knows that storm surge is the deadliest and most destructive part of most hurricanes, whether people realize it or not.

Information about surge is critical to local decision-makers.

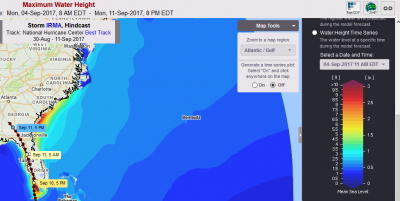

ADCIRC’s website for a time this fall was getting up to 100,000 hits per day.

But public information about storm surge can be confusing; many outlets put it out there, and from various sources. This year, for example, as Irma approached Florida, predictions of storm surge in the highly developed Tampa Bay area, where the hurricane seemed headed for a direct hit, and in Fort Meyers and Naples, ranged as high as a 6 to 9 feet.

ADCIRC wasn’t showing that. Rather, as the hurricane’s track solidified, it was showing that Irma was first going to suck the water out of Tampa Bay, leading to a phenomenon in which a portion of the bay would be, temporarily, high and dry.

And, by the time Irma’s back side arrived, it would have been over land for some time, and it would be weaker. Not only would some of that surge simply refill the bay, there’d be less wind to push it ashore.

It didn’t mean Tampa Bay’s shoreline would be out of the woods, by any means. But, Luettich said, it did mean a 6- to 9-foot surge wouldn’t likely materialize. So he wasn’t surprised when the actual surge was more along the lines of 2 to 3 feet.

“That’s pretty much precisely what we predicted,” he said.

It was partly a function of the path the hurricane took. At the last minute, Irma moved inland before it got to Naples, taking its eastern wall away from the ocean. The winds were moving west and sucked the water out first. In the end – incredible damage notwithstanding – Irma turned out to be about the best-case scenario, from a track and surge perspective, for Florida’s west coast.

Luettich doesn’t blame folks for expecting and putting out reports about the widely mentioned 6- to 9-foot surge. It’s a function of the incredible amount of attention media pay to hurricanes, and a function of the overall goal of those who put out the most, and most noticed, information.

For example, most folks rely on the National Hurricane Center. And the center’s mission is more broad-brush than that of ADCIRC and its users. ADCIRC, Luettich said, uses the advisories the National Hurricane Center generates for storms every six hours, such as wind speed, wind fields, predicted paths and wave heights to help generate its predictions.

ADCIRC, which has been refined for years, performed as one of its two lead designers expected.

Back in 2012, in another Coastal Review Online story, Luettich said ADCIRC wasn’t the first program of its kind, but was a “major leap forward,” largely because of the underlying database. Luettich’s prime collaborators at the University of Notre Dame used topographic and other crucial data from an array of sources, from federal agencies down to the county level.

ADCIRC by then had already proved its usefulness, cited in the 2012 story.

As Hurricane Irene had moved up the East Coast in 2011, Luettich said then, Joseph DiRenzo, chief of operations analysis for the Coast Guard’s Atlantic area, had placed a phone call from his office in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Luettich.

DiRenzo was worried about the Portsmouth base, which is the Coast Guard’s command center for the Atlantic, as it was on low ground prone to flooding. Though Irene wasn’t forecast to become a major hurricane, DiRenzo wanted to know what kind of storm surge to expect in Portsmouth.

At DiRenzo’s request, Luettich ran ADCIRC. It was quickly evident there would be problems in Portsmouth: Models indicated the base would be inundated. Forewarned, base commanders in Portsmouth loaded two C-130 aircraft, one carrying command staff, and flew them to St. Louis to ride out the storm and control Coast Guard operations from Missouri, 900 miles away. Not too long after that, the base was indeed flooded by storm surge and lost power.

But in that 2012 story, Luettich said the program would get better, and he now says it has. The database has of course been further refined, and the computers are faster and more powerful. He’s more confident in the predictions than he was five years ago. It’s also been improved by a continual process of looking at what it gets wrong.

“That’s often more important than looking at what you’ve gotten right,” he said, echoing a basic scientific principle. “You look at what went wrong and ask, ‘Why?’” And when you divine those answers, you refine.

ADCIRC, Luettich said, is widely used by the Army Corps of Engineers and others, including the National Weather Service, which is the parent agency of the National Hurricane Center, both part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It’s also the chief tool used by the National Flood Insurance Program, and is used by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to evaluate the flooding vulnerability of coastal nuclear power plants.

Not surprisingly, Luettich is in demand. He’s been on a long consulting assignment to help redesign the flood-control infrastructure in New Orleans, which suffered such a devastating blow from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. He still goes to Louisiana once a month to help the Army Corps of Engineers design improvements, to the tune of $14.5 billion in what’s called a “Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System.”

He leads the Department of Homeland Security Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence, and initiated the Center for the Study of Natural Hazards and Disasters to promote multidisciplinary hazards research.

He believes local and state governments are paying more attention to, and addressing storm surges issues gradually, although wind and rain still receive more media coverage, especially after the huge rainfall and record flooding in Houston from Hurricane Harvey.

Folks in the Northeast began paying more attention after Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and already, officials in Houston are paying more attention after the devastation caused by Harvey in August and September.

Luettich said that although hurricane season this year has kept him busy with ADCIRC, much of it is now automated, and there others who are capable of running the program. His role with the program is now more “forensic,” looking at the program critically after major events and helping to decide what, if anything, went wrong, and how that can be fixed.

He’s been at UNC-IMS for more than two decades now, the last 13 years as director, and doesn’t plan to leave, although he concedes he’s had opportunities.

But where would he go? North Carolina’s coast, the Morehead City-Beaufort area in particular, is Nirvana for marine science research and collaboration. Within a couple football fields’ length on Arendell Street in Morehead City alone are UNC-IMS, the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries and N.C. State University’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology. Just a few miles away in Beaufort, there are the Duke University Marine Lab and the NOAA Southeast Fisheries Science Center. North Carolina Sea Grant has a heavy presence, and there’s a national estuarine reserve named after Rachel Carson, who studied some at the Duke Lab. It’s hard to top that confluence.

Those opportunities for collaboration with other world-class teachers and researchers in various marine science fields are a large part of what has kept Luettich, and many others around for decades at UNC-IMS and those other seemingly remote outposts, miles away from their parent institutions in the North Carolina interior cities of Raleigh, Chapel Hill and Durham.

“There are very few places like this, where you can collaborate with so many others and do work that affects people right in your own backyard, in this field,” Luettich said. “I’ve always been most interested in applied research, and the coast of North Carolina has so many opportunities for that.”

Plus, he said, UNC’s main campus in Chapel Hill has long supported marine research, and has a strong program that involves not just the institute, but a thriving department in Chapel Hill. The school, he noted, is a public one, and it believes in and stresses public service. In addition to science-based involvement, Luettich served two terms as an elected member of the Carteret County Board of Education.

“I can’t say enough about the support we get here from Chapel Hill,” he said.

He also noted that the university and its marine lab have always emphasized the need for its professors and researchers to try to relate their work to local residents.

“I’ve always felt, too, that one of our most critical missions is to be involved, and to relate to, our local communities,” he said. UNC-IMS scientists try to put things in practical terms, understandable by laymen, not just scientists, Luettich said, and they also try to listen.

“There are so many times when, if you stop talking and just listen, the folks with practical experiences and knowledge can teach you, or at least provide insights that can further your interests and lead you to think about things in different ways and affect your research,” he said.

He also relishes the family atmosphere at UNC-IMS, and in the collaborations with the other facilities, and believes that’s also partly for the responsible for so many of the scientists staying in Carteret County’s facilities for long periods of time when they obviously are in demand elsewhere.

“There are many smart and gifted and driven individuals in academia, and here at UNC, too,” he said. “In many places, that can be chilling. A lot of big egos,” he said, can lead to a lot of infighting and discomfort.

But, he said, “Here, we have for many years cultivated a real ‘family’ culture that has tempered that. People do want to stay here.”

Many who work and study as graduate students under the longtime professors at IMS come back to work there if they can, Luettich said, and they also collaborate on research with IMS professors if they get jobs elsewhere.

There’s also the undeniable fact that the pressures of daily living are less than they are in more heavily populated and develop bastions of marine science.

“It’s a great ‘sandbox,’” Luettich concluded.