ROANOKE ISLAND — For the English settlers of the Lost Colony, Roanoke Inlet was irresistible. Yet in the decades after the colonists disappeared, there never was a significant permanent population on Roanoke Island, because the island was not the prize … it was the inlet.

Located 50 miles east of Edenton, Roanoke Inlet provided the best and fastest route to the Inner Banks and it was an important part of the economy of Colonial North Carolina. Although never as large or important a port as Norfolk, Virginia, or Wilmington, enough cargo passed through the inlet en route to Edenton that it was designated the Port of Roanoke.

Supporter Spotlight

In 1709, a mapmaker noted, “Ronoak Inlet has Ten Foot Water, the Course over the Bar is almost W.(west) which leads you thro’ the best of the Channel.” Ten feet of water would have been a comfortable depth for many, if not most, 18th century ships.

The inlet would eventually close. Without human intervention, about 40 inlets along the Outer Banks have silted over, closed and become part of the barrier islands.

In the case of Roanoke Inlet, it took a while for that to happen — sometime around 1800.

Soon after Roanoke Inlet closed, Currituck Inlet on the north end of the Outer Banks also closed for the last time. Temporary inlets would open occasionally, but there was no navigable inlet from the Virginia border until reaching Ocracoke Inlet. Oregon Inlet opened in the Great Havana Hurricane of 1846, but during the years after it first opened, it was shallow and unusable.

“There is not one of them (inlets) navigable north of Ocracoke inlet … Oregon inlet, has been passed through only by a small steamer of very shallow draft,” Edmund Ruffin, wrote in his book, “Sketches of North Carolina.” The book chronicles Ruffin’s travels through rural North Carolina in 1856.

Supporter Spotlight

It was a time when water transport was the engine that drove the nation’s economy and the state with the best harbors enjoyed a huge advantage … something North Carolina Gov. Edward Dudley noted in his state of the state letter to the legislature in 1838.

“The public prints in Virginia have already directed the attention of her statesmen to the feasibility of drawing the trade of our state … to their markets—to seizing upon and stripping the carcass, whilst the limbs are yet quivering with life. Shall we submit to this?” he demanded.

The answer, it appears, was “no.”

Even before Dudley took office, the state legislature had concluded that a canal at what had once been Roanoke Inlet was worth pursuing. In 1820 the Board of Internal Improvements contracted with British engineer Hamilton Fulton to survey Nags Head and provide an estimate of cost.

Twenty years later, the state turned to civil engineer Walter Gwynn. Fulton and Gwynn’s reports are remarkable for their insight. They note as an example that before Roanoke Inlet closed, what is now Roanoke Sound was a shallow marsh with a narrow channel separating Roanoke Island from the mainland.

In his conclusions Gwynn wrote “… that the opening of this channel (the Roanoke Sound) has been the cause of closing Roanoke inlet and every inlet north of it …”

The reverse is more likely true, that the inlet closed and the flow from the Albemarle River, unable to drain thorough Roanoke Inlet, created the deepest of the Outer Banks sounds as it flowed south to Ocracoke Inlet. Nonetheless, the engineers’ understanding of the relationship between Roanoke Inlet and Roanoke Sound is accurate.

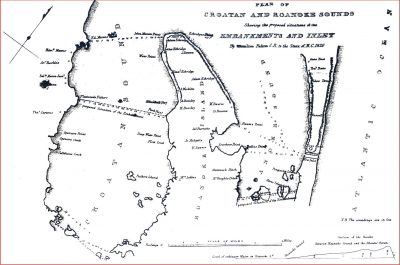

They also understood that inlets are kept open by the waters of the sound flowing to the ocean and both proposals intended to take advantage of that. What was outlined were dams on the Croatan and Roanoke sounds, forcing the waters of the Albemarle River to flow through the new Nags Head Inlet that would be created.

It wasn’t going to be cheap. Gwynn estimated the total cost at $937,770. That’s almost $23 million in 2017 dollars. Fulton’s plan was far more expensive — $2,363,463 or $41 million today.

The expense, Gwynn felt, was justifiable. “This, in my opinion, is a small amount compared with the advantages of the improvement. Indeed the great importance of the inlet to the nation at large, to the State of North Carolina, and on the score of humanity makes it difficult to name that sum ought to outweigh these considerations,” he wrote.

The federal government agreed, although not to the same degree. A modified set of plans was drawn up, which would still have cost $500,000-600,000 if completed.

In 1856 Congress allocated $50,000 and on May 13, 1856, under the supervision of Lt. William H.C. Whiting of the Corps of Engineers, construction began on a canal connecting Croatan Sound with the Atlantic Ocean.

In his 1856 travels, Ruffin witnessed the beginning of the project. An insightful observer of the North Carolina coastal environment, he felt the plans were underfunded and inadequate.

“At this time, (May 1856,) the beginning of such a canal is now in progress at Nagshead … with an appropriation of $50,000 … That sum will not go far towards completing the work. And when it is suspended, the winds alone will soon fill the excavation with drifting sand …” he wrote in “Sketches of North Carolina.”

His thoughts were prescient. After spending $40,000, Whiting, pulled the dredging equipment out and called a halt to construction in August of 1856.

A year later, in reviewing Whiting’s decision, Col. John J. Abert, chief, Corps of Topographical Engineers, applauded the lieutenant’s action.

“Congress appropriated $50,000 to commence operations; $40,000 have been expended and at this time there is scarcely to be seen … what has been done, the drifting sand filling in the trench as fast as it was excavated by the dredging machine. In fact the machine was very close to being imbedded in the sand it was filling up so fast, but it was gotten out in time to save it,” Abert wrote.

The concept of slicing through the sand at Nags Head, however, had one last chance. In 1870, Congress instructed the Corps of Engineers to re-examine the idea and report on their findings.

In a scathing rejection of the concept, Gen. James Simpson of the Corps of Engineers noted that the now widening and deepening Oregon Inlet had changed the hydrology of the sounds. If it had ever been practical to dam the Croatan and Roanoke sounds, doing so in 1870 was no longer feasible.

He also found fault with the cost estimates, calculating the price tag at $5.3 million—$103 million in 2017.

Other concerns were also noted. Maintenance costs and the effect of coastal storms were listed, leading Simpson to conclude:

“For the above mentioned reasons I respectfully submit that it would be an unwarrantable waste of the public money to apply to any such object and none in my humble judgment should be appropriated by Congress for the purpose.”