BEAUFORT – Bland Simpson’s introduction to the North Carolina Coastal Federation came in an out-of-the-blue request in the mid-1980s from founder and executive director Todd Miller.

Simpson, Don Dixon and Jim Wann had finished the first couple of performances of their musical, “King Mackerel and the Blues are Running,” and “Somebody told Todd it might be a good connection with NCCF to raise public awareness,” Simpson recalled back to 1986, when the federation was just 4 years old. “So, Todd called and asked if we’d do a show in Carteret County as part of the organization’s annual meeting.”

Supporter Spotlight

Simpson, who has a second home in Beaufort but lives most of his time about 10 miles west of Chapel Hill where he’s Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina, said that he asked Miller if he knew anything about presenting a show like “King Mack.” He didn’t.

“So, I told him what we’d need in terms of the sound and lights and other things,” Simpson said. “It’s not like putting on a concert with just a band. It’s more complicated. There’s a video component. It’s really pretty complex, so I gave him a ‘shopping list’ and he took notes and got it done.”

That was the beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship that lasts to this day, in the midst of the federation’s 35th year, and it told Simpson something about Miller: He was quiet, but purposeful, efficient and effective. He did things thoroughly, and he did them well.

That first Carteret County performance of the soon-to-be-beloved musical at Carteret Community College’s Joslyn Hall in Morehead City was almost foiled, but not by Miller or anyone else involved with the federation. Dixon was in Baltimore the day of the show, and was supposed to fly to New Bern. But the flight was held up because of storms. Dixon didn’t get to New Bern until 6:15 p.m., and the show was supposed to start at 7.

“I took off for New Bern to pick up Dixon and asked Todd to keep the crowd out of the hall until I got back,” Simpson said. “He did. We got back in time for Don to do a five-minute sound check, they opened the doors, and in just like three minutes, the room was filled. It was like, one minute nobody was in there, and then it was full. That was my introduction to Todd and the federation.”

Supporter Spotlight

The Coastal Cohorts, as Dixon, Simpson and Wann are collectively known, put on “King Mack” a couple more times for the federation in those early years. The show was then put on hiatus because Dixon, a world-renowned producer and performer, including REM and others, had moved to Ohio and Wann, a highly successful musical playwright was spending a lot of time in New York. Wann was the principal author, composer and leading man of Broadway’s Tony®-nominated “Pump Boys and Dinettes.” All three were very busy, and it was logistically difficult to get them together in one place, even for something they all very much wanted to do.

“But every year, for like six years, Todd would call and asked if we could do it again,” Simpson said. “Finally, in 1994, it was possible, and we did it in Wilmington in connection with the governor’s (Jim Hunt) ‘Year of the Coast.’ So, Todd really kicked the show back into existence and it took off.”

The cohorts did the show in New York City for three weeks, then at the Kennedy Center, and filmed it for Public Television. Over the years, they’ve also done the show as a fundraiser for the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center and the federation, jointly. Simpson said that although he loves the museum, he owes it to the federation to always include the organization in any fundraising effort in the area.

“All of this created a nice life for the show,” Simpson said. “And it really was all because of Todd’s yearly calls. I can’t over-stress the importance of the relationship, in terms of conservation in North Carolina and our role in it. It wouldn’t have happened if not for Todd’s purposeful nature.”

The relationship also led Miller to ask Simpson in 2001 if he’d serve on the federation’s board of directors. He said “yes,” and remains on it. It’s a two-year term, but there’s no “kick-off” rule. Many, like Simpson, stay on for long, long periods of time. It’s another of the organization’s secrets to success, he said: Continuity matters.

And Miller, he added, is that steady hand. While others remain in the fold, he’s the constant.

“Todd is an extremely thoughtful and very forthright man about matters,” Simpson said. “The success of the organization has been amazing, and Todd’s nature is the biggest reason for that. He chooses the organization’s battles, the things it gets involved in, very carefully. He has always wanted to get involved in things where, win or lose, NCCF can make a difference.”

Many of them have been precedent setting, and are cited by conservation organizations across the nation as the way to do things.

Simpson added that Miller, and by extension the federation, has always made it clear the way to get things done is through negotiation and compromise, at least at first. Confrontations – lawsuits and the like – can be necessary in order to preserve the coast and its water quality, but you win allies and avoid making enemies when you present facts and work with people whenever possible. You might disagree one day, but the next day you might find common ground. There’s little if any point in burning bridges, either with state government or private developers.

“That’s a big deal,” Simpson said. “And he has always stayed true to the vision. He saw early on, a need for an organization that would stitch together a lot of groups that had come together for single issues, and to keep that organization together. That organization and its credibility is what has made NCCF so effective for so long.”

A Sense of Stewardship

Simpson came to all of this naturally. He was born and lived the early part of his childhood in Elizabeth City, where his father, Bland Simpson Jr., was an attorney.

“He had a very highly developed sense of stewardship,” Simpson said. “He was not at all dogmatic, and he was soft-spoken and thoughtful. But he passed on to me his thoughts and taking care of the natural world.”

Simpson grew up in and around the Albemarle Sound and the Pasquotank River, which in Elizabeth City was at the time very polluted.

“You had all these beautiful homes on the river, but to go swimming, you had to way down the river,” he said. His father, according to an old newspaper clipping Simpson recently found, was one of a handful of people who strongly urged the local government to clean up the river. It wasn’t exactly a popular idea; it was going to cost money.

The family moved to Chapel Hill in 1959, and Simpson went to the public schools there from the sixth grade through high school, before starting as a political science major at UNC. He also took lot of English courses, and got seriously into music, thanks in part to a course he took from a professor, Dan Patterson, who had an extensive knowledge of English and southern folk songs and ballads. “Two hundred songs about Robin Hood,” Simpson quipped. But he concedes they made an impression.

Simpson also recalls folk song “singalongs” by James Taylor and his siblings, in the auditorium at Chapel Hill High School. “There’d be maybe 50 or 60 people sitting on folding chairs singing all these songs by Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary,” he said.

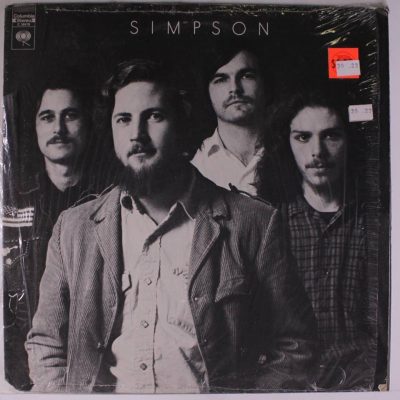

The college had a good collection of old folk and blues recordings, and while Simpson was at the time more of a “pop” musician, that influenced his style and growth. He got signed by Columbia Records and moved to New York City, where he recorded and released an album that came out in May 1971. But that wasn’t the life Simpson really wanted, and he came back to Chapel Hill. He finished school, wrote his first novel, “Heart of the Country, A Novel of Southern Music,” and got asked to teach creative writing.

Since then, he and his photographer wife, Ann, a graduate of East Carteret High School in Beaufort, have collaborated on a number of books that have taken them into and through the rivers and sounds of the state’s coast. The latest, “Little Rivers & Waterway Tales: A Carolinian’s Eastern Streams,” a lyrical part history, part travelogue, was written after exploring the state’s lesser-known small rivers, including the White Oak, Trent, New and South rivers, which are right in the Carteret County-based federation’s wheelhouse. It even has a chapter on the federation’s successful, but harrowing, movement of a house, mostly by boat, from Harbor Island to Wrightsville Beach to serve as the organization’s southern coast regional office.

Much of the research for the book was done on trips in various boats – canoe, kayak, john boat – that originated in Beaufort. Simpson said it was one of the most enjoyable projects he’s undertaken.

He loves Beaufort, and spends as much time here as possible. It’s Ann’s old stomping grounds, of course, and it’s full of like-minded folks who love the waterways and support conservation.

He’s also continued his longtime membership as pianist and singer in the legendary, Tony Award-nominated “old-time” string music band, the Red Clay Ramblers. The banjo player in that band for many years was Tommy Thompson, a good friend of that college professor whose course Simpson took. Thompson died in 2003.

In November 2005, Simpson was given the North Carolina Award for Fine Arts, the state’s highest civilian honor. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gave him a Tanner Faculty Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching in 2004. In 1999, he won the Governor’s Award “Conservation Communicator of the Year,” presented by the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, as well as the North Carolina Folklore Society’s Brown-Hudson Award for writing and music concerning state and regional heritage.

He was in Beaufort last week with Ann, who he met at the Nature Conservancy in Chapel Hill and married on Christmas Eve in 1988. He just finished a one-year stint as head of the UNC-CH English department. But he’s still a busy man, and plans to remain so. The federation will continue to be a part of that.

“I think we have done a good job, but there’s always more that needs to be done,” he said. For example, Simpson thinks the federation, while effective and well known along the entire coast, needs to begin to focus more on the inland regions where the rivers pick up pollutants and pathogens that affect coastal water quality.

“We are not the ‘Coastal’ Coastal Federation,” he said. “We’re the ‘North Carolina’ Coastal Federation. We can protect water quality all day here, and after 35 years, the public here – those who live here and many of those who visit – are much more aware of the issues, such as stormwater and impervious surface coverage. But that’s less true inland.”

Tougher stormwater rules are needed inland, and so is increased awareness of the effects dirty waters in places like Raleigh and coastal plains towns have on the waters at the coast.

“Those waters there are our waters down here,” Simpson said. And protecting North Carolina’s coast, he said, isn’t just important for those who live here and visit it here. It’s a unique place.

“It’s like (longtime East Carolina University coastal geologist) Stan Riggs says, ‘There’s nowhere else in the world where all of this exists,’” Simpson said, speaking of the “inland seas” that stretch all the way from Albemarle South near the Virginia border, through Pamlico Sound, Bogue Sound and the smaller sounds to the south.

It is, Simpson said, an intricate network of nature, a vast, interconnected system that not only supports jobs and provides recreational opportunities to millions, but also supports cultures and ways of life.

“It’s been enjoyable and very rewarding to be part of it,” Simpson said of the federation’s growth and increasing prominence in the state and beyond. “I look forward to continuing it. It’s a great bunch of people, and we’ve accomplished a lot together,” he said, but resting on laurels is not an option.