BATTERY ISLAND — When you see large white birds with red, curved beaks and red legs wading at lakes, golf courses, even backyard ponds in southeastern North Carolina this time of year, you’re seeing extreme parenting in action.

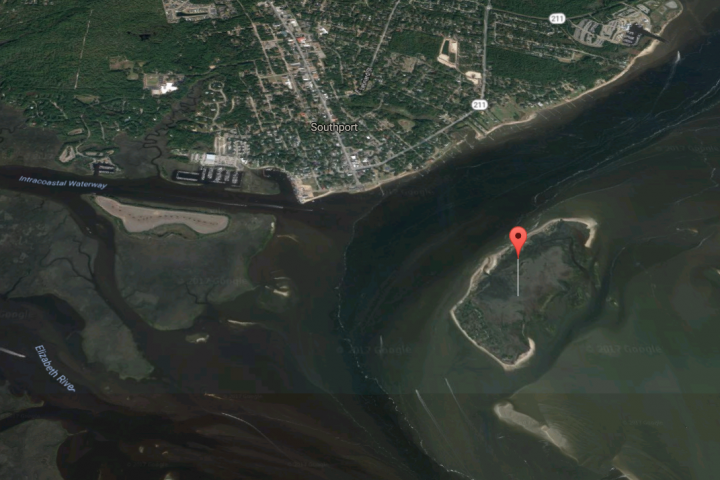

What’s attracting the white ibises, many of them part of a 10,164-pair nesting colony on the 100-acre Battery Island near Southport, are freshwater crayfish and minnows.

Supporter Spotlight

It’s not their own bellies the birds are trying to feed. It’s all those demanding mouths at home, which can be miles away from where the adults are probing in the shallows.

Unlike chicks of herons, oystercatchers and other shore birds that depend on close-to-home crabs, mussels and clams, baby ibises can’t tolerate salty food.

Just as human parents humor their infants’ dietary restrictions, the adult ibises scout out freshwater areas, like Lake Waccamaw 40 miles away in Columbus County, which have ample crayfish and then spend the summer winging back and forth to the coast with their prizes. Both males and females forage.

“If you sit on Highway 133, south of Winnabow and north of Shallotte, you can watch ibis fly over all morning long, flock after flock,” said Walker Golder, director of Audubon’s Atlantic Coast Flyway strategy.

The distinctive-looking birds started appearing in North Carolina, specifically Battery Island, in the 1960s, said James Parnell, professor emeritus of biological sciences at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

Supporter Spotlight

They’ve nested on the state-owned, Audubon-managed island at the mouth of the Cape Fear River nearly every year since then. Their numbers have grown until they’re probably one of the largest colonies in the United States, said Lindsay Addison, Audubon coastal biologist. The colony, she said, “is of global importance.”

In the first half of the 20th century, white ibis were considered Florida birds, their reputation enhanced by dazzling nature films.

“They’re one of the species that made the Everglades famous,” said Addison. “Billowing clouds of birds.”

“They’ve just gradually been moving north the last 50-60 years,” said Parnell. “It may have to do with the warming trend.”

When they swooped down on Battery Island, where their white bodies make the ibis-covered yaupon and red cedar look like flower-bedecked magnolias in the summer, they brought with them the puzzle of their foraging habits.

Scientists asked, “Why do the ibis pass up great foraging habitat to fly so far inland?” recalled Golder. Adult ibises eat fiddler crabs and other salt-marsh crustaceans, as well as fish.

“They’re generalists,” said Addison. “I’ve seen them eat water snakes.”

With plenty of food close to home, there had to be another reason they were traveling inland, especially during nesting season. That’s a time, Golder said, when “their attention is just focused on raising the chicks.”

The answer, discovered by researcher Keith Bildstein at the Belle W. Baruch Institute for Marine and Coastal Sciences near Georgetown, South Carolina, is that the chicks’ salt glands don’t develop until they’re 5 to 6 weeks old, nearly ready to fly.

In Bildstein’s experiment, “Those fed salty prey lost weight and died,” Golder said.

Once that was discovered, a second question was: Where do they go to forage?

In protecting birds, it’s as important to know where they forage as where they nest, Golder said.

So, in the late 1980s, Golder, who was writing a master’s thesis on the birds, teamed up with the pilot of a small plane to find out.

The two took off at first light, headed for Battery Island. “We circled and picked up a random group that was leaving the colony in the morning,” Golder recalled.

Since the plane flew faster than the birds, whose top speed is thought to be 30 mph, it flew in large circles above them. “We were spiraling out.” And since they didn’t want to scare the birds, they flew 1,000 feet above.

The birds didn’t seem spooked by the plane, and after reaching Lake Waccamaw, they descended into its swamps where, Golder said, “They probe around till they feel food and then they snap it out. Their bills are real sensitive to touch.”

Waccamaw State Park Superintendent Toby Hall said the birds couldn’t have found a better place. In the 1760s, famed botanist John Bartram said of the 9,000-acre wooded lake: “I think it is the pleasantest place that ever I saw in my life.”

A Carolina Bay, the lake is full of bream, Hall said, and has species of fish, mussels and snails found nowhere else in the world. “The grass beds that are out in the shallows of the lake, we call them bream beds.”

They are, he said, “a buffet” for wading birds.

He typically sees the ibis on the largely undeveloped southwestern side of the lake. It’s a good place for them because there’s not much boating or other human activity there, he added.

Not all the Battery Island ibis head for Waccamaw, however. In two seasons of tailing the birds by plane and observing them on the ground, Golder found that many go to Bald Head Island. So many, in fact, that a lake there has been named Ibis Lake.

“A great gathering spot for ibis; they feed in the lake, rest around the lake,” he said. Others fan out through rural areas of Brunswick County and into New Hanover County around Wilmington.

“I saw a flock in Brunswick County last week in a soybean field,” said Parnell. “I presume they’re getting grubs and worms.” Since they have no interest in seeds – only live prey – they present no danger to the crop.

A favorite sight from the Southport waterfront is the birds heading back to Battery Island in the evenings. They often fly in V formation – “that’s an efficient way to fly,” Golder said.

Over land, they’ll catch thermals, columns of air rising vertically as the sun warms the ground, and spiral upward, then break out of the thermal and glide.

Standing on the Southport waterfront, “you’ll see them hit that last thermal over the mainland, and glide onto the island,” Golder said.

When the chicks fledge, they are bundles of brown feathers over white underparts; they don’t molt into the white feathers of an adult until after their first year. They start learning to fly in the marshes of Brunswick County.

Adults keep feeding them as long as two months after they fledge, and many of the adults and young birds will remain in the state during fall and winter, said Parnell. “As our winters have gotten warmer, we’re seeing ibis all year now.”

There are ibis now all up the North Carolina coast and as far north as southern Virginia.

Audubon knows exactly how many are on Battery Island, which is off-limits to visitors, because they, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and volunteers conduct a painstaking ground count of nests every three years.

“You have to clamber and crawl. You can’t knock into anything; chances are each shrub has an ibis nest,” said Addison.

The current 10,164 pairs are 2,115 more than the 8,049 pairs in 2014, but not a record. The North American Breeding Bird Survey shows that, continent-wide, white ibis numbers went up 4 percent from 1966 to 2015.

“In North Carolina, they’re doing well. They have good nesting habitat, good natural areas for foraging,” said Addision.

Plus extra-attentive adults who’ll go the extra mile, or miles, to see that a new generation of ibises gets a good start in life.