CARTERET COUNTY – When the Army Corps of Engineers vessel Merritt completed some much-needed maintenance dredging in Bogue Inlet on April 20, the work was guided in part by data collected by a high-tech Carteret County firm.

Geodynamics LLC, based in Newport, has been working with the Carteret County Shore Protection Office on beach and inlet mapping projects since 2006, and has helped the county become a leader in the state in efforts to manage the beaches that draw the tourists that make the county’s economic engine hum, to the tune of about $337 million in 2015.

Supporter Spotlight

Greg “Rudi” Rudolph, head of the county agency, traces his relationship to Geodynamics founder Chris Freeman back to their grad school days at East Carolina University and UNC-Wilmington, respectively. Freeman was in the geology master’s program at UNCW, and was a research intern for a time with John Wells, a renowned geologist who was at the time director of the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. Rudolph, at ECU, worked with another of the state’s most well-known and respected coastal geologists, Stan Riggs.

Coastal geology is a fairly small world, and their paths crossed. Eventually, Carteret County wanted to take control of its beach re-nourishment efforts – get ahead of the curve in terms of the hard science about what was happening to beaches and why – Rudolph discovered that Freeman and others had started Geodynamics. Thus was formed what Rudolph calls a mutually beneficial relationship.

In 2006, Geodynamics was contracted to develop, deploy and maintain a web-based, three-dimensional virtual beach-mapping program for Rudolph’s office. It includes a plethora of coastal science data, including shorelines, topography and bathymetry, sea turtle nesting sites, sediment sample information and other natural resource information. It was the first initiative of its type in the state, according to Rudolph.

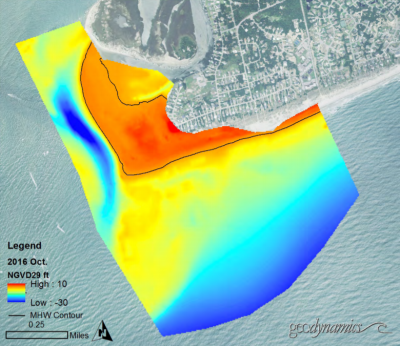

Twice each year, generally in April and October, Geodynamics takes to the water in specially built and equipped vessels to map the sea floor and does the same by walking and riding on all-terrain vehicles on the beach. Sand measurements range from the dunes to a depth of about 30 feet in the ocean, which Rudolph said equates to about a mile offshore. You can see where the sand goes, and where it stays.

The result is stunning in detail. Using dozens of beach transects, from the dunes to a specific points out in the water, Geodynamics can now tell Rudolph and the Carteret County Beach Commission how much sand has moved and where, all along 25-mile-long Bogue Banks.

Supporter Spotlight

Beach and shoreline surveys are conducted twice a year, every year, to give a complete picture of what the state of the beaches are all throughout Carteret County. Since federal money is generally not available for beach re-nourishment projects anymore, the county and the Bogue Banks towns must pay for the work when it’s needed, and Geodynamics’ information helps the county plan for when and where it will be needed. When you combine that information with cost estimates, the result is a level of readiness no one else in the state can claim.

That baseline information is also crucial in the event a hurricane does strike; without knowing how much sand is in a place, it’s difficult to know how much is lost, and that is the key to getting emergency re-nourishment money from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

But it’s not just for beach re-nourishment projects, as the dredging work in Bogue Inlet, near The Point, the western tip of Emerald Isle, shows.

In 2005, the town, with the help of grant funds, spent more than $11 million to “relocate” the channel farther west, away from the high-value and then-rapidly eroding real estate at the Point. It worked, and Geodynamics’ data shows it.

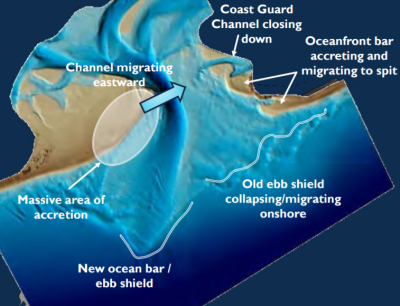

For example, Geodynamics info shows that between 2009 and 2013, the Point gained 6.77 million cubic yards of sand above the mean high water contour. However, Rudolph said, the company’s measurements also show that since 2005, the channel has migrated back toward The Point.

“Back in 2011, there was a big jump, something like 200 feet,” Rudolph said. At that time, some briefly questioned the success of the project, which at the time of construction had an estimated effective life span of 15 years. But, Rudolph said, the movement has since slowed, generally to 30 or 40 feet a year, and less in 2016.

Measuring movement, however, isn’t all Geodynamics has done. The company also designed a “safe box,” an area in which the channel needs to remain. Once it gets too close the safe box edge, it’s time to start thinking about another major realignment effort.

“Once the channel is near the safe box, our master plan dictates we move the channel back to a more equidistant position between the Point and Hammocks Beach State Park, with concurrent beach nourishment along western Emerald Isle,” Rudolph said. “To this end we have developed four ‘virtual’ transects in the inlet trending west-east, (by which) we consistently measure the channel position. This helps us quantify the sinusoidal (a mathematical curve that describes a smooth repetitive oscillation) configuration of the channel, too.

“For example,” he said, “the channel may be farther away from the safe box towards the ocean bar (ebb delta) but closer towards The Point proper. We perform a similar analysis for the shoreline at The Point by establishing a series of virtual transects using Coast Guard Road as our baseline.”

What the most recent info from Geodynamics showed, Rudolph said, is that if things continue as they have, Emerald Isle and the county should be able to put off a major inlet channel realignment until 2022, 2023 or even beyond.

That, of course, is big deal. Because recent estimates indicate a project might now cost well more than $15 million. The town has been socking away money, and the county would likely use some of the revenue accumulated over the years from the county’s tourist occupancy tax, and the local governments would likely seek help from the state, too.

But no matter how you look at it, Rudolph said, putting off that major expenditure for as long as possible is a good thing; after all half of the occupancy tax money is earmarked for beach re-nourishment projects, and while there is more than $15 million in that fund, a major hurricane anywhere along Bogue Banks could trigger a need for a project that would nearly deplete the fund.

Beach surveys have shown that there has been only minor erosion along the island in recent years, even after significant storms, but there are “hot spots” – one is in eastern Emerald Isle – that might need re-nourishment. And Rudolph said, “you knew know when that big one (hurricane) is going to hit.”

Meanwhile, guided in part by the Geodynamics data, the most recent dredging project in Bogue Inlet was a little different.

A recent survey of the southeast quadrant of Bogue Inlet showed continued eastward migration of the channel, Rudolph said, showed that a secondary ebb channel, deeper than the marked navigation channel, had formed, closer to where the old channel had been.

The thinking, according to Rudolph, was that by dredging and improving that new and deeper channel – taking advantage of the fact that it seems to be natural, i.e., where the water wants to go – the project might further lengthen the time before a major realignment is needed.

Town Manager Frank Rush said the Army Corps of Engineers had been in the area in late winter, doing some dredging for Coast Guard Station Emerald Isle, and had suggested doing the Bogue Inlet work then. But, Rush suggested that the work be delayed until April, closer to the start of the peak summer boating season. So they returned in April.

What they’ve done, Rush said, is essentially “establish a new, more central location for the connecting channel, and the Coast Guard will relocate the aids to navigation to follow the new route.

Onslow and Carteret counties, Swansboro, Cape Carteret, Cedar Point and Emerald Isle, contributed funds, with the counties and the towns picking up the lion’s share of the cost for the side-cast dredge boat to travel here and to do its work. The state also kicked in some money, left over from a previous project, from its shallow inlet dredging fund, which gets revenue from boat registration fees and from the taxes boaters pay on the fuel for their vessels. The Corps had not yet sent a bill.

Rudolph praised Geodynamics for being a “civic-minded” and doing its work a cost-effective rate the county can afford.

“They do a great job for us,” he said.

Chris Freeman, president of Geodynamics, said he agrees that the Bogue Inlet and beach-mapping projects have been a win-win for his company and the county.

“We’ve been doing this for six or seven years now … and Bogue Inlet is now one of the most studied inlets in North Carolina, if not along the whole East Coast,” he said. “In this project, we’ve learned a lot and gained a lot of insight into how inlets move and behave.”

Focusing on the Emerald Isle side, Freeman said, Geodynamics has watched “embryo” sand dunes turn into real, functioning dunes, and has seen the processes that come into play in the movement of inlets. It’s gratifying, he said, to be able to understand those processes better and to be able to look at how inlet migration can affect things like bird habitat.

Geodynamics is an eight-person operation, Freeman said, and focuses intensively on customer satisfaction; although growth is desirable, he and the others, including his wife and Geodynamics CEO, Sloan – who cut her teeth at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort – prefer to grow slowly in order to always provide quality data that makes those customers happy, and which are useful to those who need that data.

Still, the company’s work is not all in North Carolina. Geodynamics has taken on projects for clients all along the South and Mid-Atlantic, basically from Delaware to Florida, and has also done some work along the Gulf Coast, including in Texas. The client list includes, among others, the Navy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research, the Army Corps of Engineers’ offices in Wilmington, Norfolk, Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland, and the U.S. Geological Survey.

They’ve done some exciting work for the Navy, he said, including a project to help the military branch install a fiber-optic cable that runs from the beach to the edge of the continental shelf.

Freeman is especially proud that the company, while small, is committed to obtaining and using the best technology available for the work it does, even if it has to spend half a million dollars for one piece of equipment.

“We want to grow,” he said, “but we always want to keep that focus on doing what we do the best we can do it. We’re pretty specialized. It’s about quality,” he said, not quantity.

And it’s a business model that’s worked. Of the eight employees at Geodynamics, all but one, a recent hire, have been there for at least seven years.

“We’ll likely expand our office footprint fairly soon,” he said. “But we’re not about just going out and hiring more people to do something else. We are careful. We cherry-pick.”

Rudolph said he’s looking forward to the future work with Geodynamics.

“As we move forward with this program, we’re going to get even more specific with the data,” he said. “We want to look at these erosion ‘hot spots’ and try to get a better understanding of what’s going on there.”