WILMINGTON — The stretch of the Cape Fear River from Navassa to Snow’s Cut, the part fronted by downtown Wilmington and the state port here, is probably not the first thing that comes to mind when you think of the term “swamp water.”

Traffic on this section of the river, which has a 50-foot-deep channel, includes both commercial shipping and pleasure craft and the river’s current is legendary as the name of the cape itself.

Supporter Spotlight

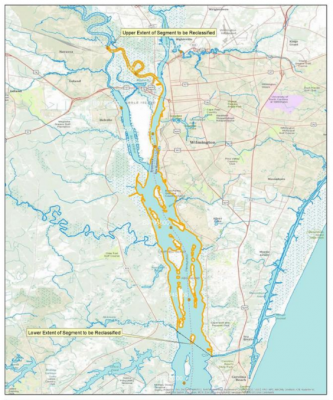

But a change in environmental rules pending in Raleigh would officially classify this roughly 12 miles of river as “swamp water,” thereby lowering the water quality standards and reducing requirements on local businesses and governments with discharge permits.

For some, including scientists who have studied the river’s depleted oxygen levels, it is a practical solution to advance regulation of the river system.

For environmental groups challenging the change, it’s an end run around important water quality rules, a move to cut discharge permit holders a break while ignoring greater threats to the river upstream, particularly from agricultural operations.

Rep. Billy Richardson, D-Cumberland, who has sponsored a bill to disapprove the new rules, said the state is playing games with water classifications.

“I just think that to hide behind a designation of ‘swamp’ when the water is clearly coastal water and clearly a navigable river is intellectually dishonest,” he said in recent interviews with Coastal Review.

Supporter Spotlight

Pointing to a photo on his phone showing a large container ship heading down the Cape Fear, Richardson said the change is baffling for anyone familiar with that part of the river.

“There’s your swamp,” he said.

In Search of a Solution

The decision to change the classification happened recently, but it was more than two decades in the making.

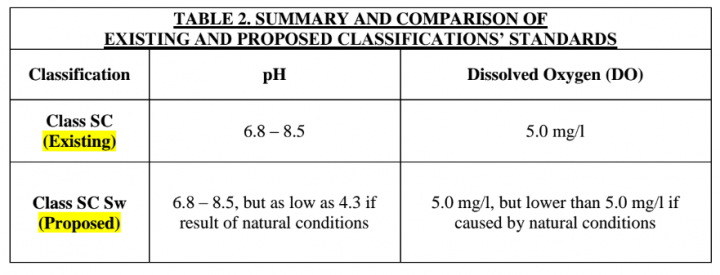

Although the Lower Cape Fear’s water quality issues are not as well-known as those of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico river systems, low pH – meaning higher acidity – and low dissolved oxygen levels landed the river on the state’s list of impaired waters in the 1990s. The designation triggered requirements that the state come up with a maximum total daily load — so-called TMDLs — for operations that discharge pollutants contributing to the low pH and dissolved oxygen. Regulators and permit holders struggled for years to come up with a workable plan.

Point-source discharge permit holders along the segment include several municipal treatment plants, Duke Energy’s L.V. Sutton power plant, an International Paper Co. mill and Invista, which makes polymers and fibers, mainly for use in nylon, spandex and polyester.

After a set of recent studies showed that restrictions on point-source discharges in the area would do little to change the overall water quality, regulators and the Lower Cape Fear River Program, or LCFRP, an association of discharge permit holders and local governments, looked for another way to move forward without imposing costly and likely ineffective TMDLs on the local operators.

In early 2014, the state’s Environmental Management Commission began exploring the idea of reclassifying some state waters as a means of getting them off the impaired waters list.

The river program reviewed the reclassification option and filed a formal request that included both the reclassification to swamp water and new rules governing how future point sources would be managed.

The request was accepted by the EMC that summer, starting a formal rules-review process.

In February 2015, the EMC held a public hearing in Wilmington on the proposal and, in September, it approved the reclassification. The proposal was modified last year and went back through the public comment process. It was approved again in May. The state’s Rules Review Commission also signed off on the plan, but it drew enough letters of objections to trigger a legislative review before it could take effect.

The legislature now has the option of directly approving the new rules, disapproving them via Richardson’s bill or similar legislation or doing nothing, in which case the rules would take effect when the current General Assembly session ends.

James Merritt, the river program’s executive director and the former director of the UNC-Wilmington Center for Marine Science, said the reclassification change made sense for a number of reasons.

“We’ve been wrestling with that problem since 1998,” he said. “We worked on modeling it for years trying to find out what the situation was.”

Merritt said studies clearly showed that the low oxygen issue would not be solved by just limiting the input from the point sources.

“The model showed it would not make much of a difference if all the discharges were actually removed from the river. It would change it very little,” he said.

The group began looking for alternatives, Merritt said, so that a reasonable way could be found to regulate that part of the river. He said after talking with DEQ, the option of reclassifying the river seemed to be the best way to get at the problem.

“That section is tidally influenced. When the tide backs up it infiltrates lowland and swampy areas around the river,” Merritt said.

The Black River and the Northeast Cape Fear, which flow into the Cape Fear just above the section contribute also contribute to swampy conditions, Merritt said.

“Our objective was to help resolve the issue such that the oxygen consuming contributions could somehow be manage and hopefully it could lead to management of the waters draining into the river,” he said. “Our hope was that they would reclassify this part of the river, set up their regulation and then work on ways to improve the river as a whole, which means deal with some of the input from upstream.”

Eliminating the reclassification, Merritt said, throws all that work out the window. “Our whole objective was to get something moving on this process,” he said. Right now, he said, regulation of the river is in a kind of limbo.

But environmentalists warn that the move sets a dangerous precedent and the plan only seeks to regulate sources with direct discharges into the river, leaving out the biggest impact on water quality for the Cape Fear.

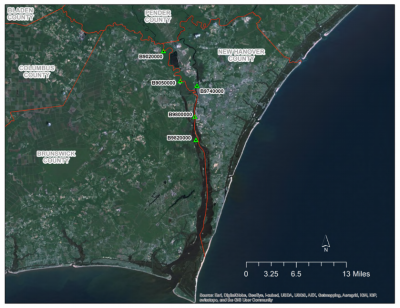

“The primary issue of concern is that by reclassifying, the state gives itself an out,” Will Hendrick, attorney for the Waterkeeper Alliance, said in a recent interview. The Black River and Northeast Cape Fear, he said, carry runoff from hundreds of hog and poultry operations downstream.

“This is the segment of the Cape Fear that first experiences the influences of upstream tributaries that drain hog country,” he said.

Hendrick said environmental organizations agree that the heavy controls on local dischargers won’t have a big effect on the river, but he’s worried that if the swamp water classification takes effect, it will put off study of the real source of decline in water quality. The flaw, he said, is that although state regulators concede it’s a factor, they don’t take into account runoff from hog and poultry operations in scientific modeling of the river’s ecosystem.

“They operate under the convenient legal fiction that they do not have an impact on water quality,” Hendrick said. “It’s pretty remarkable considering that right upstream you’ve got the highest concentration of swine farms anywhere on the globe and you’ve got a heavy concentration of poultry farms as well.”

Under the swamp water classification, if the state can attribute the conditions to natural causes, the river segment can have a pH standard as low as 4.3 and dissolved oxygen below 5.0, with no set limit on how low it can go.

“Low dissolved oxygen is a huge stressor on aquatic life and this segment of the Cape Fear is an important nursery habitat,” Hendrick said.

Two endangered species, the Atlantic sturgeon and the short-nosed sturgeon are among the fish that spend part of their early life in the river nursery before returning to the ocean.

Hendrick said the organization will review its legal options, should the reclassification take effect. He said the state needs to take a hard look at causes upstream before declaring the poor water quality the result of natural conditions.

“We don’t believe that the existing conditions are naturally caused,” he said.

DEQ spokesperson Marla Sink said the department will likely take another look at the rule changes. For now, she said, DEQ plans to wait for the legislative review process to reach a conclusion before any re-evaluation of the rule changes.

Richardson is not sure how successful he’ll be in stopping the reclassification of the river. He said he understands the impetus behind it, but said it’s better to face issues with the river, including those from upstream agriculture operations, directly rather than pretend the river is something that it’s not. The state should come up with a better way to deal with the overall problem as well as the quandary for local permit holders.

“Call it a harbor or a navigable river and make those changes that help those people,” he said, “but don’t call it a swamp.”