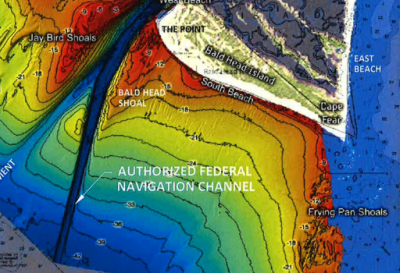

BALD HEAD ISLAND – Bald Head Island has applied for a federal permit to tap a portion of Frying Pan Shoals, an area that includes fish habitat protected under federal law, as a future sand mine source.

The shoals, a line of shallow sandbars trailing from the southeastern tip of Bald Head Island some 30 miles into the Atlantic Ocean, has no record of ever being dredged, according to the Army Corps of Engineers.

Supporter Spotlight

The proposed sand borrow area includes essential fish habitat, a federal designation that describes waters and substrate necessary for fish for spawning, breeding, feeding, or growth to maturity.

The Corps initially ruled dredging the shoals may adversely affect essential habitat or fisheries managed by the South Atlantic or Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Councils or the National Marine Fisheries Service.

The agency made that determination after the village submitted its environmental impact statement, or EIS, to build a terminal groin on the island’s western shore.

Supporter Spotlight

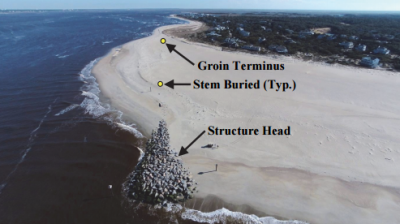

Bald Head Island received a federal permit in November 2014 to build a 1,900-foot-long terminal groin, a wall-like structure built perpendicular to the shore to mitigate shoreline erosion. Under the permit terms, the groin had to be built concurrently with the Corps’ dredging of the Wilmington Harbor Channel.

Ideally, Bald Head Island will continue to use sand pumped from the channel as groin fillet and for beach nourishment, but that all depends on how often the Corps dredges the channel.

At the time the Corps approved the terminal groin permit, the village’s preferred primary sand source for groin fillet maintenance and beach nourishment was Jay Bird Shoals “in cases where the applicant could demonstrate that dredging the federal channel was not practicable,” according to the Corps.

Bald Head Island Village Manager Chris McCall said the last time the village received sand from the federal dredge project was in 2015 when the terminal groin was built.

The Corps was scheduled to dredge the channel this winter, but lacked the funding and instead pushed maintenance dredging back to 2018.

It may be 2020 before the village receives another round of sand injections from channel dredging, McCall said.

The Jay Bird Shoals site provides a limited sand-mining source. The village received a permit in 2010 to remove up to 2 million cubic yards of sand from that site for a private project in which Bald Head pumped about 1.85 million cubic yards of sand.

McCall said officials estimate there to be 1 million cubic yards in the borrow area – not enough to last well into the future of the terminal groin.

“We’re just working through the environmental assessment and permitting process to have everything in line so that if and when we were to need to go to that borrow site it would be permitted versus waiting further down the road,” he said. “For whatever reason, whether it’s because we didn’t get sand from the shipping channel maintenance project or Jay Bird Shoals, if we needed sand, it would be complete. It would be the long-term sand source for the terminal groin project.”

The village is currently dealing with erosion along a section of the shoreline extending from West Beach up to the north entrance of the Bald Head Island Marina.

Sand being dredged from Bald Head Creek is being used to fill that section of shoreline north and south of the marina entrance, McCall said. Sand is also being pumped onto a section of South Beach, McCall said.

“As far as the terminal groin and its performance, what we’re seeing to date is it’s doing a really good job of mitigating the erosion right at the point where we were constantly struggling to maintain,” he said. “When we survey this coming spring and we take that data and the fall survey and look at and analyze it then we’ll have a much better picture in terms of quantifying the performance of the terminal groin.”

That information will also eventually help them determine whether or not the village will need to initiate a second phase of the project, potentially extending the length of the terminal groin.

Costs to dredge material from Frying Pan Shoals will be higher than pumping from Jay Bird Shoals, which is closer to the island.

The village’s proposed 460-acre sand source is on the western portion of Frying Pan Shoals, about a mile off the island’s southeast shoreline.

Under the terms of the permit application, the village proposes to monitor the borrow site immediately after dredging each year for three years, then every other year after that.

The Corps did not authorize Frying Pan Shoals as a borrow site in 2014 because essential fish habitat consultation and National Historic Preservation Act consultation were not completed.

“We will initiate EFH (essential fish habitat) consultation with NMFS (the National Marine Fisheries Service) and no permit will be issued until all requirements of the Magnuson Stevens Act are met,” Ronnie Smith, project manager with the Corps’ Wilmington district, wrote in an email responding to questions. “We will evaluate all concerns and issues as part of the DA (Department of the Army) permit process. At this time, we do not know when a decision will be rendered.”

When Bald Head filed that application last month it kicked off another assessment of the potential effects dredging may have on the shoals.

The Corps has issued a public notice that it will initiate a formal consultation with the fisheries service once the Corps has completed its essential fish habitat assessment.

The Corps’ Wilmington District is accepting written comments on permit application through March 9.