Wanted: $150,000 to $175,000 to help fund continued monitoring of water quality and to promote effective analysis and dissemination of data from Pamlico Sound, the nation’s second largest estuarine system and the largest in the Southeast. Program is FerryMon, a state ferry-based data-gathering system that helps to ensure the health of one of the country’s most valuable commercial and recreational ecosystems. Contact Hans Paerl, UNC Institute of Marine Sciences, Morehead City, N.C. Special attention: North Carolina General Assembly, North Carolina state agencies, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

MOREHEAD CITY — Hans Paerl didn’t really place a classified ad, but he let it be known, by emails earlier this month, that FerryMon, which he and Joe Ramus of the Duke University Marine Laboratory in Beaufort started back in 2000, will be kaput if someone doesn’t come up with some cash. And if that happens, the state and nation will lose a unique, cost-effective water quality monitoring system, one that has been a model for similar efforts in Florida, Massachusetts, Maine, New York, California’s San Francisco Bay and Washington’s Puget Sound, as well as European countries.

Supporter Spotlight

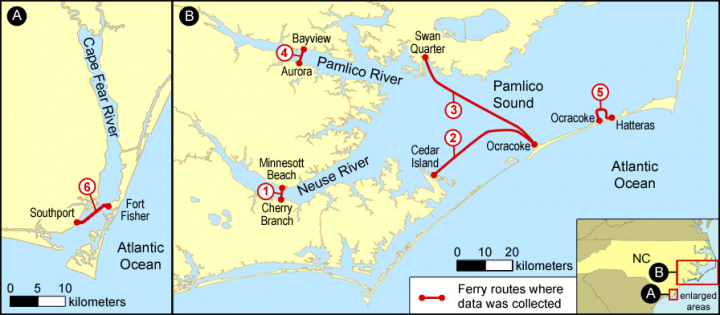

It was, back in the late 1990s when Paerl and Ramus hatched the simple concept. Several North Carolina-owned-and-operated passenger ferries crossed the state’s vast and crucial “inland sea” several times a day, every day, every year. Why not outfit those vessels with equipment to collect information on water temperature, pH, salinity and algae content? Little was known then about such things in Pamlico. It happened, thanks, in part, to money from the state legislature, which was rightfully concerned about the effects on water quality after Hurricane Floyd sent untold and unmeasurable levels of stormwater runoff and pollutants rushing down rivers to the coast in the fall of 1999.

Since then, FerryMon has survived, albeit on a shoestring budget much of the time, with the ferries crisscrossing the sound and silently sending data back to the lab, where it’s been dutifully logged, analyzed and disseminated to fisheries and water quality managers, who use it daily, as do science classrooms in some of the state’s public schools.

That stopped at the end of 2016, when a two-year, $143,000 grant from the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries expired. That grant came from a program that awards money from the sale recreational fishing licenses, but it can’t be renewed. So, Paerl said recently, the bottom line is, “We need money to cover operational costs. The instruments will still take the measurements, but we can’t pay the people to log that data, to analyze it, to get it out to the people who use it.”

And numbers without users are just, well, numbers.

“What we’d love to see is state support,” Paerl said of the $150,000 or so needed. “But we’d also like to see the state ‘go to bat’ for us in trying to get support from the Environmental Protection Agency.” EPA, after all, is responsible for the health of the nation’s estuaries, and spends a lot of money, Paerl said, on water quality monitoring and improvement in the Chesapeake Bay, not that far to the north of the Albemarle-Pamlico system. He doesn’t understand why the Chesapeake has gotten so much more federal attention. Maybe it’s because Virginia and Maryland deem it more important?

Supporter Spotlight

“We’ve been fortunate over the years to get some state support, including the N.C. Department of Natural Resources (DENR, now the Department of Environmental Quality or DEQ) and from North Carolina Sea Grant,” Paerl said. “We’ve also been fortunate to get funds for specific things from the National Science Foundation.”

But the foundation generally funds only specific research, not the basic measurements that FerryMon provides. And state support – at least from the legislature – dried up years ago. FerryMon, in fact, started with support from Sea Grant and the state Hurricane Floyd Relief Fund to document the effects of the hurricane’s floodwaters on the Pamlico Sound. At one point, most of the $300,000 per year was coming from the General Assembly’s annual budget appropriations.

When that stopped, the fisheries division grant, eventually, filled the gap, temporarily. But Paerl said the Pamlico system is too valuable – worth $4 billion in fisheries and recreational economic benefits – to let monitoring of its crucial parameters to fall by the wayside.

“It just makes too much sense – it’s so economical from a cost-benefit standpoint – for someone, the state, the EPA, a partnership of the two, not to pick this up and ensure that it continues,” he said. “The operational costs are very reasonable for the data that the program yields.”

The way FerryMon works is simple: Water taken in by the ferries to cool their air conditioning systems is diverted through a black box below deck. A set of sensors constantly monitor water temperature, acidity, salinity and algae content. The data are sent to the lab over the Internet. The data are charted so officials with the state agencies, including but not limited to the Division of Marine Fisheries, can monitor it and react and know what to expect and tell the public.

FerryMon can, for example, provide information to let the fisheries division know where fish kills are likely to occur because of low salinity levels or low dissolved oxygen levels. And the information on nutrient levels – phosphate and nitrogen, which in sufficient levels lead to algae blooms and other water quality problems – help the state agencies monitor the total maximum daily load, or TMDL, which has been set for the nutrient-sensitive Neuse River, which feeds into the Pamlico system. A spike in nutrient levels noted by a ferry, for example, can clearly signal that something’s badly awry in the Neuse.

As recently as 2016, after Hurricane Matthew swept through the area, FerryMon provided important data about the water flowing toward the coast from torrential inshore rains. Although major problems didn’t occur, the data generated from the ferry’s monitors could explain that. In addition, Paerl said, the instruments collected water quality data for all but 36 hours during the passage of Hurricane Isabel in 2003. When compared to Hurricane Floyd, the program increased basic knowledge of how different storms have different effects. FerryMon, Paerl said at the time in an article in “Coastwatch,” a North Carolina Sea Grant publication, “showed us that windy but low-rainfall hurricanes like Isabel exerted much less severe and shorter duration of negative impacts on water than high-rainfall hurricanes like Floyd. During Floyd, floodwaters caused multiple algal blooms and led to stressful conditions for fish and low oxygen conditions throughout the sound system for more than a year.”

That same Coastwatch article, Paerl pointed out, detailed how measurements from FerryMon after Tropical Storm Ernesto in 2006 showed that high amounts of chlorophyll in the Neuse River, resulting from increased nutrients flowing down the river in the storm’s rainwater runoff, led to a mid-estuary bloom of the toxic dinoflagellate that was closely linked to fish kills reported after the storm.

It might be hard, Paerl said, for some to understand the importance of the basic, baseline knowledge that FerryMon and programs like it provide. But knowledge inevitably informs policy, and policies in large part determine the water quality that will affect the quality of life of future generations in and around the Pamlico Sound region. In general, Paerl said, the more information we know about a gigantic estuary that is critical to the state’s fisheries and its economy, the better decisions we can make.

He remains optimistic that somehow, some way, he’ll find funds to keep FerryMon operational. He calls it a “suspension,” not a “termination” of the program.

Paerl said he’s contacted the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership and is trying to work with state legislators as well as Gov. Roy Cooper’s administration.

Cooper is widely seen by environmentalists as more friendly to environmental initiatives and funding of programs, and Paerl agrees, but said FerryMon has had bipartisan support in the past, especially from coastal legislators who have understood its value.

“This shouldn’t be political,” he said of the program and its generation of basic knowledge about one of the state’s most crucial environmental/economic resources. “It’s cost-effective, it’s been a model for many others, and it works. The concept has caught on. We’ve been pioneers: First in Flight, first in FerryMon?”

In the meantime, the Paerl Lab at UNC-IMS continues to use other grants funds, from Duke Energy Foundation, to keep FerryMon up-to-date in hopeful anticipation of its continuation.

The foundation last year provided $95,000 to UNC-IMS to construct two portable, ferry-based water quality monitoring systems for ongoing assessments of water quality along the Neuse River and Pamlico Sound ferry routes.

The idea is that the equipment will be transferrable in the event ferries are disabled or must be replaced.

“I have to be optimistic,” Paerl said. “It’s a good program, and an important one.”

It’s particularly important in light of growing threats to marine ecosystems as the world’s climate grows warmer and more unstable.

For example, the EPA recently proposed standards for cyanobacteria, which can, in sufficient quantity and under the right conditions, produce liver toxins called microcystins and cylindrospermopsin, which is toxic to the kidneys.

Paerl is an expert in the field, and recently said both toxins are increasingly common worldwide, including in North Carolina, and threaten not only recreational waters, but also water supplies.

Problems like than one put more of an impetus on water quality monitoring: Cyanotoxins found in August 2014 in a water-treatment plant in Toledo, Ohio, forced the governor to declare a state of emergency and issue a boil-water advisory that lasted for several days. That water came from Lake Erie.

“Water quality monitoring is crucial,” Paerl said. “I’m not going to be around forever, and I’d like to leave it (FerryMon) in good shape for the future.”