MOREHEAD CITY — The Environmental Protection Agency is developing standards to protect swimmers and other recreational users of the nation’s waterways from toxins produced by what are believed to be among the oldest microorganisms on the planet.

Hans Paerl thinks that’s a good thing.

Supporter Spotlight

Paerl, the Kenan Professor of Marine and Environmental Sciences at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, is one of the world’s leading experts on cyanobacteria. Sometimes misleadingly called blue-green algae, cyanobacteria can, in sufficient quantity and under the right conditions, produce liver toxins called microcystins and cylindrospermopsin, which is toxic to the kidneys.

Unfortunately, as Paerl said recently, both toxins are increasingly common worldwide, including in North Carolina, and threaten not only recreational waters, but also water supplies. Paerl has been studying the problem for years in China, where Lake Taihu, the drinking water supply for millions of people, has been threatened by microcystin.

It’s the same toxin that in August 2014 was found in a water treatment plant in Toledo, Ohio, forcing the governor to declare a state of emergency and issue a “boil water” advisory that lasted for several days That water came from Lake Erie.

“Cyanobacteria are basically the cockroaches of the aquatic world,” Dr. Timothy Otten, a postdoctoral scholar in the Ohio State University College of Science and College of Agricultural Sciences, said after the incident in Toledo. Paerl put it this way: “They are the true ‘cell from hell’” under the right conditions.

It’s a classic case of “too much of a good thing,” Paerl added, because cyanobacteria are believed to be the first organisms to produce oxygen on earth, some four billion years ago.

Supporter Spotlight

“They figured out how to split water and, through photosynthesis, produce oxygen,” Paerl said. “We have them to thank for that, because unless something else had figured that out, we wouldn’t have oxygen.” In other words, we wouldn’t have “we.”

The problem, he said, is that other substances – mostly phosphorous and, especially, at least in recent years, nitrogen – dramatically stimulate the growth of cyanobacteria. And the increased use of nitrogen-based fertilizers to grow crops has helped to rapidly proliferate cyanobacteria almost everywhere.

Since the organisms are bacteria, they also thrive on heat. And Paerl said, no matter what “climate-change deniers” say, temperatures almost everywhere in the world are setting new records. The bacteria also are tolerant of salt, so some can thrive in saltwater as well as freshwater.

“Climate change provides an additional catalyst for their expansion,” Paerl wrote in a recent paper on the subject. “Rising global temperatures and changing precipitation patterns both stimulate (cyanobacteria and their toxins) … and their maximal growth rates occur at relatively high temperatures, often in excess of 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit). At these elevated temperatures, cyanobacteria routinely out-compete (algae and other organisms in the water).”

In addition, the cyanobacteria, which thrive in calm waters, shade organisms below them, such as phytoplankton and aquatic vegetation, from the sun. And as higher temperatures last longer during the average year, blooms are likely to start earlier in spring and last longer into fall. Even without toxin production, they can be harmful, reducing oxygen levels in waters as they age and die.

Cyanobacterial surface blooms can locally increase surface water temperatures, because of light energy absorption, according to the paper written by Paerl and Otten. And since climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme rainfall events, “This will lead to larger surface and groundwater nutrient dis-charge events into water bodies.”

When there’s excessive freshwater discharge, blooms may be prevented by flushing, at least in the short term. However, when the water stays put longer, the nutrient load from rainfall can then be sequestered.

So, according to the paper, conditions most likely to result in excess cyanobacteria can be expected to begin with elevated winter-spring rainfall and runoff, followed by protracted periods of summer drought. Examples can be seen in the Neuse River and its estuary, the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

The EPA’s proposed standard for microcystins, the more ubiquitous of the two toxins, is 4 micrograms per liter, which Paerl called reasonable. The toxin can cause problems not only for humans, but also for pets and fish. For cylindrospermopsin, the proposed standard is 8 micrograms per liter.

The EPA’s proposed standard for microcystins, the more ubiquitous of the two toxins, is 4 micrograms per liter, which Paerl called reasonable. The toxin can cause problems not only for humans, but also for pets and fish. For cylindrospermopsin, the proposed standard is 8 micrograms per liter.

The World Health Organization sets the standard for microcystins in drinking water at 1 microgram per liter, Paerl said, so it’s clear that the toxin is a serious threat.

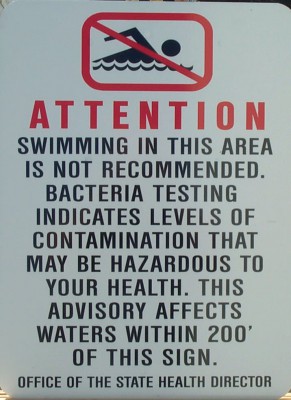

The EPA’s recent announcement states that if the proposed standards are approved after the 60-day comment period ends on Feb. 17, they could be used by states in water quality standards, and as the basis for swimming advisories at beaches.

According to the EPA’s notice in December, “Certain environmental conditions, such as elevated levels of nutrients, warmer temperatures, still water, and plentiful sunlight can promote the growth of cyanobacteria to higher densities, forming what are called harmful algal blooms (HABs). Elevated cyanotoxin concentrations in surface waters can persist after the bloom fades, so human exposures can occur even after the visible signs of a bloom are gone or have moved downstream.”

Cyanotoxins, according to the EPA, “are released into the water as cyanobacteria grow and die. You can be exposed to elevated levels of cyanotoxins if you swim, play in, or recreate on or in a water body where cyanobacteria may reproduce rapidly. Toxins can be ingested, inhaled or absorbed through the skin. The toxins’ persistence in the environment can potentially affect downstream users, such as drinking water utilities and swimmers and boaters, where the bloom may not be directly observed.”

Health effects from cyanotoxin exposure in pets can include vomiting, diarrhea, seizures and skin rashes. Pets may be exposed to cyanotoxins if they drink water contaminated by cyanobacteria, lick their fur after swimming in contaminated water or ingest toxin-containing algal scum or mats. Pets can also be exposed if they drink tap water contaminated with cyanotoxins.

Because children spend more time in the water than adults and often swallow more water per body weight while swimming, EPA derived the recommended criteria based on children’s recreational exposures.

Paerl said that once the EPA approves standards, he hopes North Carolina will follow suit.

“It is a real problem here, and it’s growing,” he said. “In fact, when I arrived here back in the late ’70s, the first project I took on was a massive (outbreak of cyanobacteria) in the Chowan River.” That one was traced back to phosphate and nitrogen from fertilizer and ineffective treatment at a wastewater-treatment plant. Eventually, the phosphate discharge was greatly reduced, and it helped alleviate the problem.

Back then, Paerl said, no one was paying much attention to the toxins from cyanobacteria, so not much if anything is known about microcystins from that event. But he has no doubt there were toxins present.

There have also been cyanobacteria problems in Jordan Lake, the water source and an important recreation site for many in the Raleigh area, and in the Cape Fear River.

There’s also little doubt that those toxins are dangerous. The sites of the worst cyanotoxin/microycystin problems in China are known also to be areas with high incidences of liver disease, including liver cancers.

“In fact,” Paerl said, “China is one of the best places in the world to study the issue,” because, while liver tumors can take decades to show up, people in those areas of China tend to stay there their entire lives, drinking from and recreating in the same waters for decades.

North Carolina, Paerl said, has done a good job limiting phosphorous, and has done a particularly good job in the Neuse River Basin, which was declared “nutrient sensitive” years ago. But the state has not done nearly so good a job on nitrogen, which is increasingly the main factor in production of cyanobacteria and their associated toxins.

While some farmers still use too much nitrogen-based fertilizer too close to the water, that problem has been ameliorated significantly by public education. And, Paerl said, farmers and individual property owners who use fertilizers have been receptive to that education.

But, he said, waste-treatment plants can, and should, do a better job of reducing nitrogen discharge, though it’s expensive.

“They (treatment plants) are really the low-hanging fruit,” he said. “Sure, it would be expensive. But I’d argue that it’s well worth the expense. We’re talking about our water supply.”

In addition, he said, urban development has become a proportionally larger part of the problem. Too many want to develop lawns and golf courses, for example, right down to the water.

Paerl said developers in places like Raleigh and Charlotte are likely the largest pressure point in recent legislative discussions about reducing or eliminating vegetative buffers along streams. Vegetative buffers are the best “low-tech” method to keep nitrogen from flowing into streams via stormwater runoff.

Whether a state legislature averse to environmental regulation would buy into efforts to further address the nitrogen problem is “anyone’s guess,” Paerl said. But he said the public already understands the need to protect not just coastal waters, but also drinking water supplies and recreational waters.

North Carolina, he added, is not alone in the need to do more.

“When I went to Ohio after the Toledo event, I headed up a mitigation discussion, and I was surprised to find out how little buffering there is around agriculture there and in the Midwest. North Carolina is at least ahead in that respect.”

Paerl would like to see more urban developers and planners make use of constructed wetlands, like the recently converted ponds off N.C. 24 in Cape Carteret, because wetlands plants are very efficient at taking up nitrogen. He credited the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which took on the Cape Carteret project to improve water quality in nearby Bogue Sound, for effectively promoting and helping to create buffers and constructed wetlands.

The whole cyanobacteria/toxin problem, Paerl reiterated, is likely to be exacerbated by climate change. He’s especially worried about increasingly hot areas of the United States, such as Florida and Southern California. Blooms have already plagued Lake Okeechobee in Florida and Lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana, and there are big concerns regarding lakes used for recreation and water supply in Oklahoma and Texas.

But Paerl and others are also worried about cooler regions; San Francisco Bay, for example, has suffered from microcystins. High levels of the toxin were detected in mussels in the bay in October, and low levels have been found in oysters. Back in 2010, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife reported that sea otters had died of microcystin poisoning – otters eat shellfish. The bay is fed by numerous rivers that roll through agricultural lands and industrial areas.

There’s also a need, Paerl said, for better monitoring of the problem. For example, FerryMon, a project Paerl and colleagues set up in 2000 to monitor water quality in North Carolina’s Pamlico Sound, the nation’s second-largest estuary, has run out money from one of one of its major sources of funds, a grant from the Division of Marine Fisheries (See related story).

The program, which Paerl said Tuesday can no longer operate because of the lack of funding, has used specially equipped Department of Transportation ferries that cross the Neuse River, Pamlico River and Pamlico Sound to determine water quality effects of storms, hurricanes and nutrient and pollution discharge, and to establish a database which can monitor water quality status and trends.

The end of the project could make the data less available to managers. Paerl said it’s an inopportune time for that to happen. The state needs to do a better job of obtaining federal funds for water quality monitoring, as officials in Virginia and Maryland do for programs in Chesapeake Bay, he said.

“This (cyanotoxins) is a real thing, not a figment of anyone’s or any agency’s imagination,” Paerl said. “European countries have been involved for some time. It’s something we all need to address, and protecting our water supply and the health of humans who enjoy using the water for recreational purposes is something EPA is supposed to do.”

Comments to the EPA are due by Feb. 17.