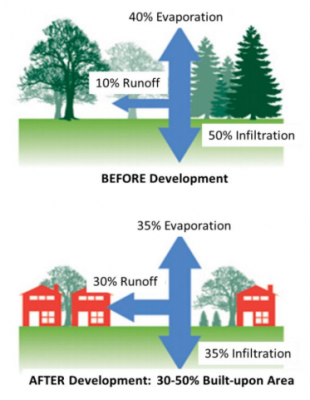

The benefits of keeping stormwater runoff out of waterways are well known, but what if that runoff is viewed as potential drinking water – is it as valuable as the water that flows from the kitchen sink?

Research from the Environmental Protection Agency, indicates that if the stormwater can make it back into the ground, it could be worth as much as that in the drinking water supply.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think this is a great piece of data – it’s another great way to talk in economics about the value of doing these stormwater reduction projects,” said Tracy Skrabal, coastal scientist with North Carolina Coastal Federation, of the study. “When we put water back into the ground and it is cleaned as it is infiltrating, then we are resupplying that resource that provides us with drinking water. That’s intuitive, but to put the value on it of hundreds of millions of dollars per year – or billions of dollars cumulatively – is really valuable.”

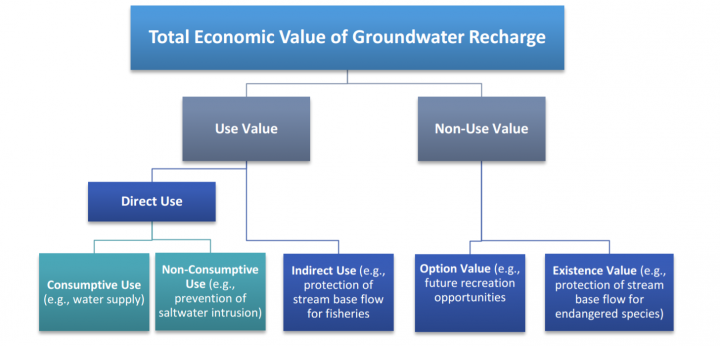

The study, “Estimating Monetized Benefits of Groundwater Recharge from Stormwater Retention Practices,” estimates the benefits of groundwater recharge from the application of small stormwater retention practices on new development and redevelopment across the country.

Stormwater that makes it back into the ground could be worth as much as $225 million annually as drinking water, according to the study.

“This analysis was undertaken as part of the effort to estimate monetary value of the co-benefits of stormwater retention policies to inform policy makers,” Enesta Jones, a spokesperson for the EPA, said. “Stormwater retention policies are driven for different reasons, this study was to assess the potential economic benefit. While groundwater recharge may not economically drive retention, it should be noted as a side benefit of the water quality and stream protection. “

Skrabal agreed that placing a monetary estimate to stormwater would be an addition to the list of benefits of managing runoff.

Supporter Spotlight

“We talk about these projects in terms of multiple benefits, so groundwater recharge is one of them,” she said. “Those (estimated values) don’t even touch the value of keeping polluted stormwater out of our creeks and rivers and streams. So when you look at the overall valuation in terms of having clean waters and development around that, and recreation, the number must be enormous.”

Skrabal called the study further evidence that there is more than just environmental benefits to managing stormwater.

“It actually is a financial or economic benefit to the state and relates to something that is pretty critical in our state, which is adequate water supply,” she said. “So I think this piece of data should drive not just public policy, but also should help the state justify making more changes to their programs to allow these better infiltration practices.”

values. Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Bridget Munger, a spokesperson for the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, which manages the state’s stormwater permitting program, said the department is open to looking at new research and data that could improve the program and provide more flexibility for developers in choosing how they want to manage stormwater at a particular site.

“While the state’s stormwater program has not yet studied the economics of infiltration and groundwater recharge, our engineers are always looking at innovative ways to provide design options that will protect water quality, while providing additional environmental benefits,” Munger said. “Program staff work closely with researchers at N.C. State University, as well as diverse stakeholder groups, in that effort.”

She explained that new stormwater rules developed this year by the state require infiltration in areas of active shellfish harvesting waters whenever it’s technically feasible. In areas outside active shellfish harvesting waters, developers can choose the stormwater control measures best suited to their projects, though the state provides options for infiltration devices that follow specific guidelines.

Annette Lucas, an engineer with the state Department of Environmental Quality’s stormwater permitting program, said permit applicants have 12 options for treating stormwater with methods varying from more traditional wet ponds, where water settles into a manmade pond, to complex bio-retention ponds that infiltrate stormwater through a series of plants, sand, clay and other organic materials to increase the rate in which the water goes back into the ground. Other methods include pervious pavement, rain gardens and more.

“The person who owns the property gets to choose how the stormwater is treated,” Lucas said. “But we’ve made a lot of changes that make it easier to do infiltration, to do bio-retention. We’ve taken away in our design (of the stormwater rules) some of the things that unwittingly prevented people from making that choice. So a lot of times people are choosing to do bio-retention and infiltration, but there’s a lot of factors that go into making that decision that are really site specific.”

“As we move Down East, we have trouble with high water table. So you might have great soil for infiltration, but the soils are saturated with groundwater,” she explained, noting the need for a wide range of stormwater treatment choices.

“I think over time people are choosing more of the low-impact type systems,” Lucas said.

Skrabal said she believes North Carolina has been “very aggressive” in its approach to managing stormwater runoff through innovative, low-impact development techniques, like vegetative swales, rain gardens, bio-retention areas and more.

More attention should be paid to redevelopment and retrofitting opportunities, she said, as well as moving away from the more traditional methods of stormwater treatment, like wet ponds, and encouraging or requiring more use of the low-impact development techniques.

“I think (the EPA study is) just another sort of confirmation of what we already know, and that is: When you can employ low-impact development techniques during new development, it is going to be financially beneficial to the community, but also to the developer,” Skrabal said. “We know that a lot of these techniques are actually cheaper in the long run to employ than what I would call old-school stormwater retention ponds and detention ponds. It just makes good financial sense all around to do this.

“And the added benefit of reducing the volume of polluted stormwater in our adjacent waters – that’s a win-win for everybody.”