Humpback whales are making a comeback.

More than 40 years after being placed on the endangered species list, most populations of the giant marine mammal are believed to be thriving and no longer meet the definition of a threatened or endangered species, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Service.

Supporter Spotlight

Some conservation groups are calling the status change premature and say humpbacks still face many threats and need the continued protection of the Endangered Species Act.

“While humpback whales are recovering thanks to the tremendous power of the Endangered Species Act, (NOAA Fisheries) shouldn’t be in a hurry to declare the job complete when so many threats are on the rise,” said Kristen Monsell, staff attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity.

Monsell cited entanglements in fishing gear and other threats as a top concerns for humpback whales.

“Entanglements are definitely a concern for humpbacks on the East Coast,” she said. “Research using entanglement-related scarring data indicates that up to 65 percent of the Gulf of Maine humpback population has experienced entanglements.

“Ship strikes are another concern for humpbacks on the East Coast, as are increasing threats from climate change, ocean noise and offshore aquaculture.”

Supporter Spotlight

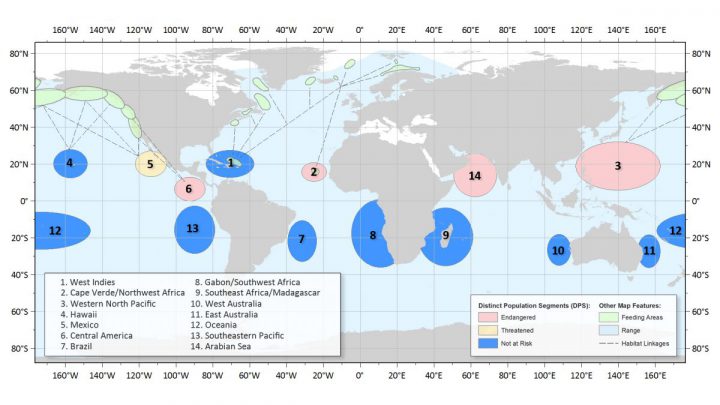

NOAA Fisheries, which has jurisdiction over 147 endangered and threatened marine species under the Endangered Species Act, has classified 14 populations of the world’s humpback whales. Nine of those populations, including the West Indies population that migrates along the East Coast, have been determined to be recovered and no longer meet the definition of an endangered species.

One population that migrates along the West Coast has been classified as threatened, while the remaining four populations are still considered endangered. Those five populations will continue to receive all the protections of an endangered species, said Angela Somma, chief of NOAA Fisheries’ endangered species division.

“NOAA Fisheries made this decision following a comprehensive status review,” Somma stated in an email. “We continue to monitor and work to address whale entanglements in fishing gear, but we are confident that many of the humpback whale populations have rebounded.”

But the thriving populations of humpbacks are not without protections.

“There are other important protections that continue to remain in place, even if certain populations are not listed under the Endangered Species Act,” Somma said during a press call in September. “The Marine Mammal Protection Act, which is a comprehensive conservation law for the protection of marine mammals, still applies. (Humpback whales) will still be protected comprehensively under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.”

Somma noted that because the Marine Mammal Protection Act carries many of the same or similar protections for marine mammals as the Endangered Species Act, there would be few practical implications in terms of protection of humpbacks.

“For the populations that are no longer listed under the Endangered Species Act, federal agencies will not be required anymore to consult (with NOAA Fisheries) when they want to undertake an activity that might affect those populations,” Somma said, although such agencies may need authorization for the effects of their activities on humpbacks through the Marine Mammals Protection Act.

“Many of the day-to-day protections and activities (for humpback whales) will continue to occur,” Somma said. “We will continue to work and maintain their conservation under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.”

Humpback whales were once widely hunted for their oil, meat and baleen, or whalebone. The oil was used for burning lamps and making soap, while baleen was used for all sorts of items, from backscratchers to corset stays.

It wasn’t until 1946 that commercial whaling worldwide was formally regulated. In 1966, the practice was banned altogether by the International Whaling Commission, and the moratorium on commercial whaling has been in place ever since, though some subsistence hunting is allowed for certain native peoples in the Arctic.

Then in 1970, humpback whales, along with many other species, were designated as endangered with the passing of the Endangered Species Conservation Act. That legislation was replaced in 1973 by the Endangered Species Act, which continued the humpbacks’ endangered status.

“At the time (humpbacks) were listed, there were a number of large whale species that were put on the endangered species list when the Endangered Species Act was passed,” Somma said. “We didn’t have specific population abundance estimates at that time, but it was well known that humpback whales, as well as many other species of large whales, had been severely depleted due to commercial whaling.”

But humpback whale populations have “increased substantially,” Somma said, thanks to the end of commercial whaling and protections of the Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammals Protection Act. But exactly how much they’ve increased is hard to estimate.

“Our status review does talk in terms of having a population of at least 1,000 animals to ensure that there is at least some level of viability, but it’s not a hard and fast number,” Somma said, adding that the 1,000-animal goal applies to each of the 14 humpback whale populations.

According to NOAA Fisheries data estimates, there are somewhere around 80,000 humpback whales in the world’s oceans, with 10,000-12,000 of them, the West Indies population, swimming up and down the East Coast of North America. The same number of whales is estimated to be living in the Hawaii population in the Pacific Ocean.

The largest population, West Australia, is estimated to have around 21,000 whales. The four remaining endangered populations – Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa, Western North Pacific, Central America and Arabian Sea – may have fewer than 1,600 humpback whales combined.

Marta Nammack, the national Endangered Species Act listing coordinator for NOAA Fisheries, said threats against the four endangered populations include fishing gear entanglements, energy exploration and development, vessel collision and climate change.

She noted that some threats are more severe than others depending on the region of the whale population, and that in some cases, such as with the Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa population that may have fewer than 100 whales, there simply isn’t enough data to justify removing the whales from the endangered species list.

Somma said that climate change was a factor in the analysis of the humpback whale populations, and is one that will continue to be looked at, along with other threats to humpbacks, in the future.

“As a general matter, NOAA Fisheries is trying to assess the potential impact of climate change on all of the species for which we manage so we can better understand how to manage them in the future,” she said. “For those (humpback) populations that will no longer be on the endangered species list, we have developed a monitoring plan for the next 10 years to continue to assess their status.

“That monitoring plan is not specifically targeted at climate change but it certainly is going to look at the health of those populations. And if there are any changes in those populations, the monitoring plan is designed to help us understand why that might be occurring.”