Whether they regard oysters as delicious delicacies or repulsive lumps of slime, North Carolinians should rightfully rejoice at the construction planned this winter of a new oyster sanctuary at the mouth of the Neuse River. Down-home oyster roasts and upscale oysters-on-a-half shell dinners are hotter than ever in the local food movement, but more oysters also mean cleaner water and a more resilient ecosystem.

As part of public-private partnership, the North Carolina Coastal Federation and the state Division of Marine Fisheries is readying construction of the Swan Island Oyster Sanctuary on 40 acres of a 60-acre site in Pamlico Sound, the first of a multi-year effort to significantly expand the state’s oyster industry.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think it’s huge, said Steve Murphey, the division’s habitat enhancement section chief. “It really puts us on a new level. These are above the levels we were planting in the ‘90s.”

The reef will be constructed in long mounded ridges of mostly recycled oyster shells and fossil rocks about 3,500 feet long, he said, with areas between the 40 acres of reefs left open to allow for habitat for other marine life. The work will be done 20 acres at a time. Once it’s done, it will resemble a wide ladder, with “rungs” between the ridges spaced 70 to 90 feet apart.

In addition to construction of the reef, the state also plans to build a place where baby oysters can settle in and hire two staff for the program that leases water bottom for oyster farming. All are funded by a $1.3 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and matching state funds.

Murphey said that the Swan Island project represents an important step toward the state’s long-term goal of having 500 oyster reefs that will substantially increase oyster population, and by extension, the commercial harvest. North Carolina is far behind its neighbors Virginia and Maryland, which can boast of a booming oyster industry.

“The hard thing to understand about oyster habitat is that oysters are their habitat,” Murphey said. “So if you only put out 100-200 bushels of oysters for cultch every year, you never gain any ground. If the goal is to really increase production of oysters, then you really have to ramp up oyster habitat.”

“Cultch” mean any material, usually oysters shells, that laid down on oyster grounds to furnish points of attachment for the spat, or baby oysters.

Supporter Spotlight

Hand in Glove

Native oyster larvae will settle naturally on such constructed reefs and when left alone, will grow and spawn millions of eggs that float on currents, ideally landing on a cultch planting. Fish also find the reefs to be attractive habitat.

The location of the cultch site has yet to be determined, said Erin Fleckenstein, a federation biologist. The Division of Marine Fisheries will hold public meetings in the fall to help site the cultch plantings.

The Swan Island sanctuary bears a critical inter-relationship to the cultch site, she said.

Larva travels in the water column from the sanctuary. When they settle they become spat.

“Its purpose is to create the babies that land on the cultch areas,” she said. “They feed each other and they work hand-in-glove.”

Although the sanctuary will not be open to harvest of oysters, it will be open to hook and line fishing. The federation will hire a contractor to deploy the material and build the reef.

The sanctuary was selected, Fleckenstein said, by a stakeholder working group that determined an appropriate area with no environmental and commercial fishing conflicts that did not overlap with existing shellfish areas. Construction is expected to begin in February and be completed within six months.

A similar process will select other areas for sanctuaries and cultch plantings in 2017 and 2018, when an additional $1.5 million a year is anticipated from the NOAA grant. Although a state match is technically not required to secure the money, Fleckenstein said, a minimum equal match of non-federal dollars is recommended to maintain a high ranking for the application.

Building an Industry

Ultimately, the long-term vision of the partnership is building sustainable wild oyster reefs, Fleckenstein said, and a robust oyster aquaculture industry, a winning combination of economic opportunity and environmental benefits.

Each adult oyster can filter about 50 gallons a day, removing nutrients and cleaning the water. The reefs can also serve as natural breakwaters and help stabilize shorelines.

“It all comes back to this overall blueprint we have for oysters,” she said. “It’s a comprehensive plan that looks at all things oyster.”

That is good news for North Carolinians who fish, farm or eat oysters.

“It’s great that we’re finally getting attention from Raleigh,” said Jay Styron, president of the North Carolina Shellfish Growers’ Association.

Harvest of wild oysters is currently about 15 percent of what it was at its height in the early 1900s, Styron said, when 1.8 million bushels were harvested. Pollution, disease, over fishing and habitat loss conspired to decimate the shellfish, and by the mid-1990s, less than 35,000 bushels were harvested.

“When you look at it from a historic perspective, it’s still a drop in the bucket,” Styron said about current harvest.

Construction of reefs and cultch plantings will go a long way toward restoring the oyster industry in the state, he said. “In due time, it should increase it,” he said. “I don’t know if we’ll ever have a wild harvest that will fulfill the market.”

Farming Oysters

That’s where oyster mariculture – aquaculture in saltwater – comes in. There are two markets in the state, Styron explained: shucking oysters that are wild-caught, and oysters-on-a-half shell that are grown on farms. Styron owns an oyster growing operation on Cedar Island, Carolina Mariculture Co.

The half-shell market is new and growing nationwide, he said. “People are discovering oysters again,” Styron said.

Not only are they nutritious, he said, they’ve become popular in the food market, pairing upscale oyster meals with select wine or beer. The farmed oysters have the same sized and shaped shells, making portions easy to control. They’re the same species as the wild oysters, but they grow faster and their shells are not as, well, wild.

“So we give them a more consistent product,” Styron said. “The wild-caught oyster is like getting a big bag of potato chips. Ours is like a container of Pringles.”

Styron leases 6.5 acres of sound bottom, producing about 200,000 to 250,000 oysters a year. It takes about a year or less for seed oysters to reach market size, with peak production at 18 months; wild oysters need about three years. Also, he can harvest all year long; the commercial season for wild oysters is October to March.

But there’s room enough for farmed oysters and shucking oysters.

“Our product is so different,” he said. “We don’t compete with the wild oyster customers. The market we’re going for is white-tablecloth restaurants.”

Robbie Mercer, owner of I & M Oyster Co. in Lowland said that he thinks that North Carolina should do “spat on shell” as Virginia and Maryland have done in their very successful oyster restoration program. The method cultures spat in tanks to set on oyster shells, where they grow into a dozen or so tiny oysters that are not as vulnerable as when larvae floats to a cultch to grow.

Military veteran Jared Mayhew, who farms oysters on the May River in South Carolina for his J&W Oyster Company. This is sweet video about a man making a living for himself while respecting the ecosystem and promoting local food ways.

Playing Catch Up

But North Carolina has a way to go to catch up to Eastern Shore oystermen, who can catch their limit within hours.

“We had seven or eight guys we were buying oysters from last year,” Mercer said, “and I can probably count on two hands when they reached their limit for the day.”

He said he probably bought and sold a couple of thousand bushels of wild oysters last winter. He said he pays the fishermen the same price the Maryland Eastern Shore waterman are paid, over some local griping. “I told them it was the same as us stealing,” he said, “so I drove the price up for the commercial guys.”

His profit margin is about $5 bushel, so the more he moves off his dock, the better for everyone. “I would love to have 400-500 bushels a day,” he said.

Mercer is in his second season of growing oysters, and estimates he has sold 400,000 oysters so far for the year. He has two 5-acre leases.

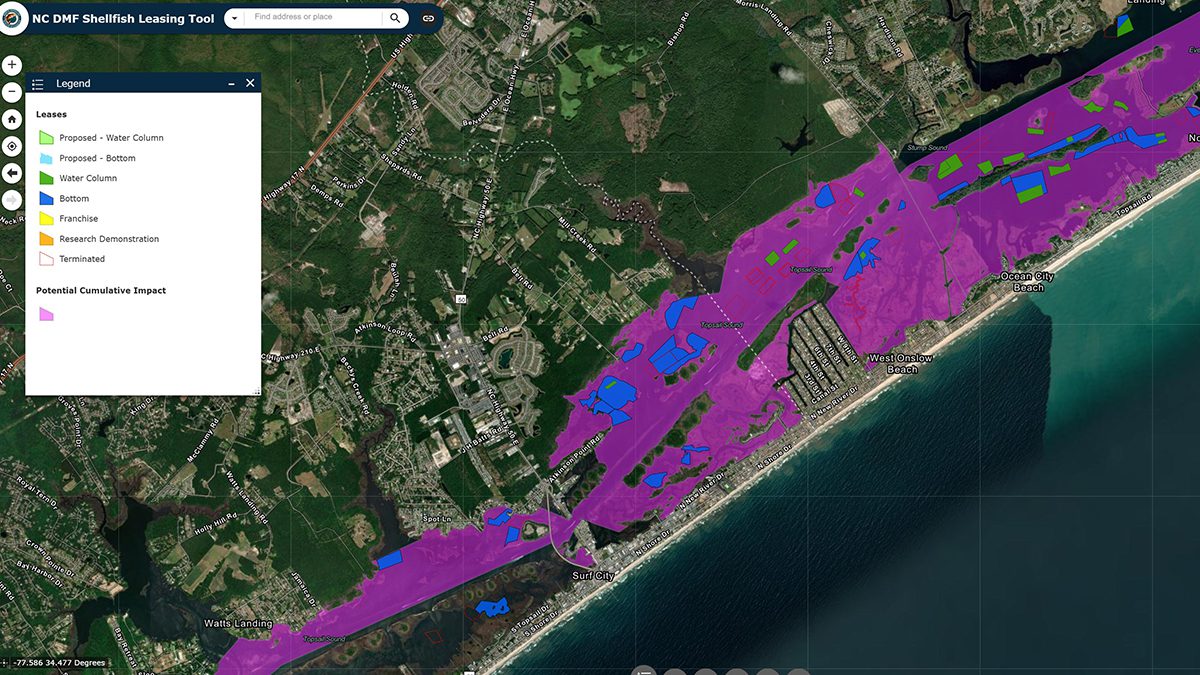

He said that the two new staff members the state will hire for the shell bottom leasing program can only improve service. Until now, all the leasing has been handled by the shellfish map section, Murphey said, which admittedly was not able to adequately provide the service.

“The primary need we have right now is it takes a lot of time to do site evaluation,” he said. “It’s a lot of field work, a lot of boat time.”

When the two staff are hired, one person will divide time between field work and sampling for GIS mapping. The other staff person will focus on data analysis and communication with the lease applicant.

The shellfish lease program, Murphey said, has been operated with a bare-bones budget of $5,000, barely enough to pay for fuel. “So we’re real excited to actually get a budget,” he said.

The state grants 10-year leases of public sound and river bottom. Leases are renewable, but they must meet certain levels of production. There are currently about 290 shellfish leases and franchises approved in the state.

Buying Oyster Shells

Murphey said that the state buys oyster shells from every shucker in the state, but the state’s recycling program has proven to be costly and inefficient. At its peak, the state was handling 25,000 bushels a year, he said. Now it’s 5,000 bushels.

Murphey said that the state buys oyster shells from every shucker in the state, but the state’s recycling program has proven to be costly and inefficient. At its peak, the state was handling 25,000 bushels a year, he said. Now it’s 5,000 bushels.

“You’ve got to have a storage area, and then you’ve got to go get them,” Murphey said.

Between the need for dump trucks and trailers, and staff time, he said, it is cheaper to buy oyster shells in volume from commercial dealers. The state is currently evaluating dealing with only the larger contributors.

Where Murphey is upbeat about realizing big advances in management of oysters, some veteran watermen will point-blank disparage the program; others say they’re skeptical about putting more reefs in fishing waters.

“Anything like that is good for the commercial guys as long as they allow harvesting,” Mercer said. “Anytime the word ‘sanctuary’ is put out there, to fishermen it’s a total closure.”

Dale Newman with Newman’s Seafood in Swan Quarter, comes from a long line of oystermen. “My dad is 72 years old,” he said. “His daddy worked on sailboats oystering. I reckon my great-grandfather on my mother’s side shucked oysters.”

In his experience, oysters naturally come and go. Back when he was younger, he said, management meant harvesting them when they were there, and leaving them alone for a while when they weren’t.

Newman said there has been a lot of criticism of oyster management, but he believes that under Murphey’s leadership, Marine Fisheries is working in a promising direction.

“I think we need to give them a little bit of time,” he said. “We have had a very hard time communicating with each other. We really don’t truly understand each other. We’ve got to get together and manage the oyster resource better than it’s been managed. We need to start talking with each other and listening to each other a little bit.

“I’m hoping they’re going to start doing things a little bit differently,” he said. “I’d much rather be on the same page.”