BEAUFORT – The chairman of the panel that manages coastal development rules wants to create a new term that downplays the perils of owning beach property near coastal inlets.

Frank Gorham, chairman of the state’s Coastal Resources Commission, suggested Wednesday changing the name of the areas designated as inlet hazard zones to something that sounds more positive. His suggestion came during the 13-member commission’s meeting at Pivers Island near Beaufort.

Supporter Spotlight

“We’ve always had the issue of no one wants to be in an inlet hazard area,” Gorham said. “Where do we stand on maybe renaming it?”

During an interview immediately following the two-day meeting that began Tuesday, Gorham suggested “inlet management area” or “inlet-affected area” in order to “encourage people to participate, as opposed to run away from it.”

The North Carolina Division of Coastal Management defines an inlet hazard area as shorelines that are especially vulnerable to erosion and flooding where inlets can shift suddenly and dramatically. Gorham made the suggestion during a presentation by the commission’s science panel, a 10-member group that provides commission members scientific data and recommendations.

While no decisions were made regarding the name, Spencer Rogers of Wilmington, vice chair of the Coastal Resources Advisory Council, told the commission that erosion rates can be 10 to 15 times greater in inlet zones than elsewhere.

An inlet hazard area is one of a number of terms used to designate various zones barrier islands in the 20 coastal counties subject to Coastal Area Management Act of 1974. The CRC’s responsibilities include setting policy, designating areas of environmental concern and granting exceptions, or variances, to coastal development rules.

Supporter Spotlight

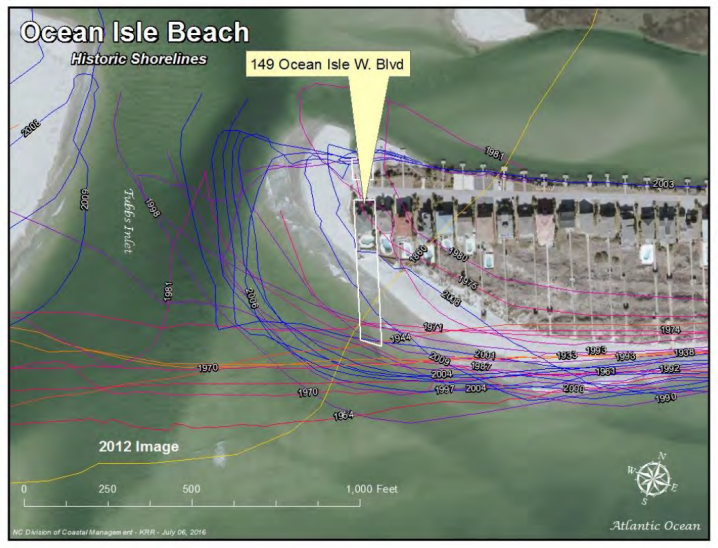

The commission on Tuesday granted four such variances, all that were requested for this meeting, including one for a property on an inlet hazard area at the west end of Ocean Isle Beach in Brunswick County.

The Ocean Isle case involves a home on Tubbs Inlet, which was designated an inlet hazard area in 1979. The owner, Kay Picha, bought the lot in 2003. The piece of land owned by Picha is dynamic, with sands shifting heavily over time. As recently as 1980, her lot was underwater.

Four years after she purchased the property, Picha requested and was granted three CAMA general permits to place sandbags along the oceanfront and inlet side of her property after the home was determined to be threatened by erosion. Two years later in 2009, Picha was permitted to place additional sandbags for five years on the inlet and rear side of the property, which overlooks a creek.

Sandbags are considered a temporary measure of protection from erosion and must be removed within eight years, as set in the permit, though few actually are. Picha’s sandbags were never removed and in April, Picha applied for another CAMA permit to add more sandbags to those in place, for which time had run out. Picha sought to also to increase the size of the sandbag wall beyond the commission’s authorized size limits. In June, the Division of Coastal Management, citing the excessive size of the proposed sandbag wall and the expiration of the existing permits, denied the application. The division staff also expressed worry that sandbags could fall into the inlet, a public trust area, and become a hazard to navigation, among other concerns. “Removal of such displaced sandbags would be very difficult given the dynamic nature of the inlet, increasing the possibility that these sandbags would present a future navigational hazard within the inlet channel,” according to a legal summary by the division staff.

Despite the objections from staff, the CRC approved the variance, allowing the height of the sandbag wall to double at about 12 feet.

Picha’s attorney, Clark Wright of the Davis Hartman Wright law firm of New Bern, argued that the “accelerated eastward movement” of the Tubbs Inlet channel “now immediately imperils” Picha’s sandbag wall, thereby also putting at risk her home and the private road and public utilities serving it and a number of other homes on the west end of Ocean Isle Beach.

The channel had moved about 77 feet closer to the western edge of Picha’s sandbag wall between Nov. 25, 2015, and June 19 and was now only three feet from the sandbags.

“This movement represented an increase of several hundred percent over prior years’ average monthly movements,” according to Wright’s letter included in the agenda materials for the meeting.

Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic, a senior policy analyst at the North Carolina Coastal Federation who was present at the meeting, said the sandbags approved for the project will end up on public trust waters, or waters below the mean high water mark that belong to the public.

“The way the proposed structure design was presented does not show the structure below mean high water mark,” Zivanovic-Nenadovic said, “but if the bags were put in today, with the present configuration of Tubbs Inlet, they would certainly be below mean high water.”

Commissioners also voted on changes to sandbag rules on Wednesday, appearing to take a slightly different view on the temporary structures than during the variance discussions.

In a 7-2 vote, the CRC opted to do away with sandbag permit renewals in favor of one-time sandbag permits.

Some commissioners said they worried that allowing property owners to apply to renew sandbag permits every eight years, even in the face of imminent threats, provides little incentive for towns to seek other measures of erosion control, such as beach re-nourishment or construction of terminal groins.

“I don’t think that’s good,” said commissioner Larry Baldwin, echoing the advisory council’s advice against multiple permit renewals stated earlier in the day.

The division staff is expected to present the commission in September a new draft for sandbag rules that changes the permit renewal language, adding back in the requirement that towns must be “actively pursuing” beach management and incorporating the one-time permit rule.

Sandbags have long been considered a temporary solution to a growing erosion problem on the coast.

Zivanovic-Nenadovic said sandbags were originally meant to be two-year temporary structures. However, the new rules being developed by the CRC, including extending the permit to eight years, are making the structures more permanent. The result is often a loss of public access.

“They benefit private property owners, but interfere with public’s right to use dry sand beach because they are placed on the public trust,” she said. “They can also increase erosion rates in front of the structure, on the ocean side of the bags. In addition, they can become a hazard during storms and they can break up, litter and obstruct access to the beach.”

Commission members offered differing opinions during their discussion of permit renewals. Gorham said that homeowners looking to sell their homes would not want sandbags on their properties because they lower property values.

“Nobody wants to have a house with sandbags,” Gorham said. “There is an economic incentive to cover up the sandbags.”

Commissioner John Snipes responded, asking what incentive there would be if a property owner wanted to stay. “What if I don’t want to sell my house?” he said.

Gorham said restrictions on sandbag permits will result in some desperate property owners seeking a variance from the commission as their only option, which can be a slow process.

“That’s hard to tell people,” he said. “That’s my problem.”

Mark Hibbs, Coastal Review Online’s assistant editor, contributed to this report.