Hundreds of people gas up every week at the Get N Go on U.S. 13 in Windsor, unaware of what might be happening under their feet. The convenience store and gas station is owned by Zero Investments, which was fined more than $14,000 last year for violating seven state environmental laws, including failing to investigate suspected releases from its network of underground tanks and pipes that store and move gasoline.

The Get N Go is one of seven gas stations in coastal counties that were penalized in 2015 by state environmental regulators for failing to properly maintain or operate their underground storage tanks, or USTs. Petroleum spills can contaminate groundwater, harm the coast’s sensitive aquifers and for residents on private wells, taint their drinking water for decades.

Supporter Spotlight

New spills, coupled with a backlog of more than 5,000 release sites, present an intractable financial situation for the state. While the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality estimates it needs at least $800 million to help clean up the backlog of releases, only $30 million is available a year for the Commercial Underground Storage Tank Trust Fund.

While North Carolina has more commercial USTs than most states, ranking ninth in the nation in tanks per person, it receives substantially less revenue for its program, roughly one-third of the national average.

The shortfall is the largely the result of cuts by the state legislature to the UST fund, which helps those responsible for petroleum spills clean them up. Last year, lawmakers cut the budget for the UST fund by $600,000, according to Robin Smith, a former assistant secretary for the Department of Environment Quality who now writes an environmental policy blog. And instead of an annual appropriation from the state’s Highway Fund, which would have stabilized the UST program’s revenue, Smith wrote, lawmakers eliminated that source of money, worth $13.3 million, in 2015.

Instead, lawmakers implemented one-time funding and tacked on a legislative review to determine whether the trust fund should be continued. But at current funding levels — primarily from state motor excise taxes, tank operating fees and small federal grants — a DEQ analysis concluded, it would take until 2046 to clean up the old sites, some of which are already more than 20 years old.

More than 720 of the overdue sites are in DEQ’s Wilmington and Washington regions, which encompass 28 counties in the coastal plain.

Supporter Spotlight

To begin whittling away at the backlog with such little money, DEQ last month began changing the focus of its clean ups, based on risk assessments at each site. The bulk of the money will go toward remediating, or at the very least stabilizing, the 1,761 highest-risk sites — those close to drinking water wells, wetlands, rivers and even city water utilities. There are 312 such sites in the Wilmington and Washington DEQ regions.

The lower-risk locations — those the agency deems unlikely to harm human health or the environment — will receive less UST fund money, about $500,000 per year. Instead, DEQ will monitor those discharges and rely on “natural attenuation” — in other words, time — for the contamination to subside.

“It would be ideal if funding was not an issue and the decision could be based on the best available technology” to clean up the sites,” reads the DEQ’s new policy, released on June 1. “However, it is certainly not very realistic.”

Aware of the financial burden on states, the EPA approves of the use of risk-based standards in cleaning up UST sites. North Carolina has followed suit, says Art Barnhardt, DEQ’s Underground Storage Tank section chief, “as a tool to control the costs.”

At 792 sites, the risk to human health and the environment is unknown. Half of the sites, classified as low- or intermediate-risk, are subject to less stringent groundwater standards. Known as Gross Contaminant Levels, they allow concentrations of certain chemicals and compounds to be 1,000 times greater than the state 2L standards. 2L is named for the section of state administrative code that regulates groundwater standards.

For example, hexane, a chemical commonly extracted from crude oil and petroleum, can damage the stomach and lungs, if swallowed. Under 2L standards, groundwater can contain no more than 400 parts per billion of hexane; that’s equivalent to 400 drops of water in a 10,000-gallon swimming pool. Under Gross Contaminant Levels, 400,000 drops of water would be permissible in the same pool.

The 2L standard applies to a minority of sites based on risk, says Barnhardt, and freeing up dollars would allow regulators to scrutinize and more quickly remediate them.

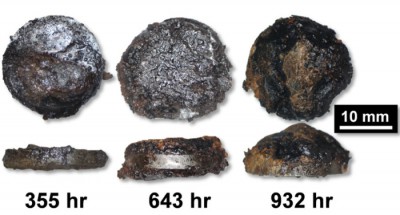

Scientists have discovered that petroleum spills go through phases. Initially, the plume expands in groundwater. Depending on the area’s geology, the plume can travel through fractures in underground rock or migrate via porous soil. At this point, it’s important to contain and clean up as much of the contamination as possible. But later, between five and seven years, Barnhardt says, the plume can begin to stabilize. And eventually it can contract.

However, state regulators still don’t know which phase — expanding, stable or contracting — each of the 5,000 sites is in. Barnhardt says the UST division has only recently begun using monitoring and site data to divine that information through computer modeling. “We don’t know the numbers yet,” he says.

Contamination from leaking USTs is common. Since the state legislature established the UST fund in 1985, there have been more than 19,000 reported discharges, both commercial and residential, into groundwater and soil throughout North Carolina, according to DEQ records. Many commercial discharges happen at some of the state’s 9,000 gas stations. Non-commercial spills often occur as the result of leaks in residential heating oil tanks.

The UST Fund helps business owners remediate the damage from those releases. Since the fund’s inception, the state has spent more than $600 million on cleanups. Under current regulations, the businesses — “responsible parties” — must pay a deductible of $20,000 to $75,000 before tapping the fund. They also have to pay an annual fee of $420 per tank and carry at least $120,000 in insurance. “We need that level of financial assurance,” Barnhardt says.

In North Carolina’s coastal plain counties, there are 301 UST Fund sites, worth a state investment of $5.4 million since 2011, according to DEQ records.

As early as 2004, federal environmental officials expressed concern about the solvency of the Commercial UST Trust Fund. A 2007 Government Accountability Office report concluded there was not enough money in the fund to address all of the state’s high-risk sites. And in 2009, North Carolina ranked in the top 10 states in the number of backlogged sites, according to EPA documents.

The financial situation, and thus the backlog, has not improved under the Republican-led state legislature. “There just isn’t enough funding,” says Katie Hicks, associate director of Clean Water for North Carolina. “That’s the core of the problem.”

The state’s new budget, passed last week, appropriates money to the UST fund based primarily on a small portion of revenues from the motor fuels excise tax, in addition to tank permit fees. However, it’s unclear how much money that would generate, since lawmakers voted last year to decrease that excise tax rate by one cent.

And none of this funding includes a state-lead program that adopts commercial sites whose owners have gone bankrupt, can’t meet the deductible or can’t be located. There are 1,200 of those sites statewide, with only $3.5 million available to fund the cleanups. “We can’t go in as aggressively,” Barnhardt says. “If it’s a high-risk site, we do what we can to stabilize it.”

The future of the UST program is precarious. Last year, the state legislature eliminated the Noncommercial UST Trust Fund, which covered the cleanup costs for property owners. The program ends in December. Property owners will now bear the entire cost of clean up, which could become complicated when land is bought and sold.

And the state could get out of the Commercial UST Trust Fund business altogether. In a January 2016 presentation from DEQ to legislators, the agency noted that the General Assembly should consider continuing a source of revenue for the fund “during transition to privatization.”

Without the UST fund, companies would have to buy private environmental insurance and finance a clean up themselves. And if they couldn’t — or wouldn’t — the state could be required to intervene to comply with federal environmental law. With what money, though, is uncertain.

To Learn More