OCRACOKE — Our story is inextricable from that of pirates. The birthing pains of our colony were eased by services rendered from those sea dogs that once took harbor in places like Beaufort, Wilmington and Ocracoke Island as Gov. Charles Eden practically institutionalized the revolving-door relationship between them and the colonial government.

It is for this reason that any self-respecting North Carolinian knows at least a little something about pirates. And so in order to set the tone here, how about a pop quiz to test your swashbuckler savvy.

Supporter Spotlight

Let’s start with an easy one. Who is the most famous pirate in the world (Johnny Depp does not count)?

That would be Blackbeard, of course.

Can you name one pirate that hailed from North Carolina?

Chances are, you answered Blackbeard – unless you’re a pirate nerd and didn’t say Blackbeard just because it would be too easy and cliché.

Who partied with Charles Vane on the beaches of Ocracoke like it was 1799 (although it was actually 1718)?

Supporter Spotlight

Blackbeard again.

Which pirate was beheaded in Ocracoke Inlet, whose body is said to still be seen swimming around on full moon nights in search of its missing head?

Blackbeard.

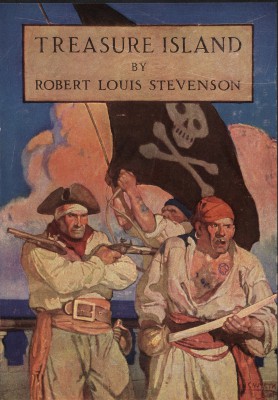

Who stole the largest treasure ever pirated in the Atlantic Ocean from inside of Ocracoke Inlet, was chased by five different countries, buried the treasure on a remote Caribbean island and stands as the foundation for nearly every single pirate story ever told from “Treasure Island” to “Pirates of the Caribbean?”

John and Owen Lloyd.

Who?

Wait a minute. You have never heard of John and Owen Lloyd? They only stole 52 chests of Spanish silver in 1750, worth around $20 million in today’s dollars – far more than Blackbeard ever dreamed of capturing. This was the most famous act of piracy in history. Owen lived on Queen Street up in Hampton, Va. He did the whole buried treasure thing in the Caribbean. John Lloyd was from Church Street in Norfolk. He was the guy with the wooden leg who owned a 150 acres on the Pasquotank River. Doesn’t ring a bell? Maybe you know John by a different name he was given many years later: Long John Silver.

I’m underneath a thick canopy of live oak trees at a place called Springer’s Point on Ocracoke Island. Some of the live oaks are pretty old in here and more reminiscent of places I’ve been along the coast of the other Carolina to the south. Yaupon holly, that coastal shrub with its caffeine-infused leaves, is ubiquitous. A flash of red, blue and green flits passed me and I pause because I have never seen a painted bunting on Ocracoke Island. The air hangs thick with humidity and salt, and I can’t help but think of some of the other pirate haunts I have explored along the coast of Belize, Honduras and Panama.

Up ahead, the wall of dark and green opens to Ocracoke Inlet. An old rock jetty extends into the water where a few years back I sat in a kayak, pulling in both gray and speckled trout with every single cast until my arms shook from exhaustion and I had to weigh the options of catching more fish or being able to physically get my kayak back to the ramp and on top of my truck. At the end of the jetty is a hole. Surrounded on all sides by shallow water on an ebb tide, this slough still bears the name of Edward Teach – the man we call Blackbeard today.

Teach’s Hole, as it is known both here on Ocracoke and on official navigational charts of the inlet, is probably the site of the two biggest things to happen in the world of piracy during the 18th century. It was here that Blackbeard slept off a hangover in his sloop when Capt. Maynard, the man who would separate him from his head, sailed into the inlet. And it was here where a couple of sloops where stolen by John and Owen Lloyd, separating Spain from an immense treasure larger than anything ever stolen in the Atlantic.

On Aug. 18, 1750, the legendary Flotas de Indias, Spain’s treasure fleet, set sail from Havana toward the Florida Straights and the Gulf Stream. Late August really isn’t the best time of the year to be sailing the Gulf Stream without advanced weather forecasting. Though hurricanes can technically pop up from June till the end of November, hurricane season is a lot like basketball season in that only four of those weeks really matters.

The weeks between Aug. 20 and Sept. 20 is when the likelihood of a hurricane more than doubles. Since 1851, when records began to be kept on such matters, there has been 34 hurricanes to affect the coast of North Carolina in the month of July, 101 in August and 142 in September. Every major hurricane to hit North Carolina has occurred in this late August through late September window of time. And so when on Aug. 25 Capt. Bobilla, of the Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, the flag ship of this year’s treasure fleet, first took note of darkening skies to the east as they rounded Cape Canaveral to the west, the hurricane season of 1750 was shaping up exactly as we have come to expect.

The hurricane deposited three wrecked Spanish galleons onto the list of North Carolina’s Ghost Fleet. On Aug. 29, the NS de El Salvador was dashed to pieces on a sandbar somewhere between Beaufort Inlet and Cape Lookout, the Soledad ran aground near Drum Inlet, and the Guadalupe came to rest near Ocracoke Inlet at Portsmouth Island and broke apart.

Only a small amount of silver that washed ashore was recovered from the wreckage of the El Salvador. As for the Soledad and Guadalupe however, all treasure and cargo made it through the storm to be unloaded onto the beaches of Core Banks – including the 12 tons of silver aboard the Guadalupe.

The Spanish Treasure Fleet was not the only ships to turn up at Ocracoke Inlet as a result of this storm. John and Owen Lloyd were in route to St. Kitts down in the Caribbean when the hurricane drove them into the inlet in desperation. The Lloyds ran a shipping and ferrying business around Hampton Roads but both brothers had suffered at the hands of Spanish privateers during the recently ended King George’s War. John, the older brother, had found himself short one leg thanks to a Spanish cannonball before being captured by another privateer and stuck inside of a Havana prison. Owen himself did a short stint as a privateer and successfully captured at least one wealthy prize around the Virgin Islands before his ship was captured by the Spanish near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, for which he fell into financial ruin.

The particularities of exactly how two Spanish-hating brothers from Hampton Roads came to be commissioned by Capt. Bonilla to ferry his “cargo” to Norfolk for shipping back to Spain has been lost to the shifting sands of the islands history. But, in short order John and Own Lloyd found themselves working aboard two sloops anchored in Teach’s Hole as a skeleton crew of Spaniards that had survived the hurricane loaded 52 chests of unknown contents into the cargo holds of the small shallow drafting boats. Can you see where this is going?

The particularities of exactly how two Spanish-hating brothers from Hampton Roads came to be commissioned by Capt. Bonilla to ferry his “cargo” to Norfolk for shipping back to Spain has been lost to the shifting sands of the islands history. But, in short order John and Own Lloyd found themselves working aboard two sloops anchored in Teach’s Hole as a skeleton crew of Spaniards that had survived the hurricane loaded 52 chests of unknown contents into the cargo holds of the small shallow drafting boats. Can you see where this is going?

It did not take long before word spread as to exactly what was in those chests. On the heels of a war with Spain, with a bunch of people who had either directly or indirectly suffered at the hands of Spanish privateers standing around as eyewitness, on an island as remote as the moon is for us today, in a colony that had long embraced and harbored pirates in order to benefit from their tax free services, here was a king’s fortune laying around on the beach in a bunch of boxes. This was a powder keg waiting to explode. And by now everyone was trying their hand at a plot to grab the silver.

The North Carolina council argued the chests should be seized because they were illegally landed on N.C. soil. Custom officials were busy doing what custom officials did at the time trying to ransom part of the treasure for themselves. As for the Bankers who inhabited Ocracoke, these folks had long made their living by scavenging shipwrecks and as the story on the Outer Banks goes, there had always been a blurred line between law-abiding citizen and outright pirate on the Outer Banks. This fact alone was enough to prompt Eden to try and dispatch the HMS Scorpion to protect the silver from the locals on the island.

John and Owen’s plan was pretty simple. While Bonilla was busy fighting with the N.C. government to procure customs papers in New Bern, they would simply hack the anchor lines and slip out the inlet with the falling tide. While everyone else was busy trying to find legal loopholes that allowed them to lighten Spain of this burden of silver, the Lloyds would simply steal the ships it sat upon. And what a fitting place for the whole thing to transpire: on Ocracoke, where Blackbeard and Charles Vane had plotted to create another Pirate Republic in Nassau like fashion, and in Teach’s Hole to top it all off. It took little convincing to pull together a small crew for the job.

On Oct. 20, 1750, as the Spanish soldiers left the two sloops loaded with silver and boarded what was left of the Guadalupe as they did every day for lunch, two sets of anchor lines were cut. Sails were quickly raised, and crowds of onlookers, both on land and on surrounding ships, erupted in cheers as John and Owen Lloyd raced out of the inlet and into the open waters of the Atlantic. Their destination: St. Kitts, in the British Virgin Islands.

On Oct. 20, 1750, as the Spanish soldiers left the two sloops loaded with silver and boarded what was left of the Guadalupe as they did every day for lunch, two sets of anchor lines were cut. Sails were quickly raised, and crowds of onlookers, both on land and on surrounding ships, erupted in cheers as John and Owen Lloyd raced out of the inlet and into the open waters of the Atlantic. Their destination: St. Kitts, in the British Virgin Islands.

In the 1750s, if you spoke English, Spanish, or French, you knew about the Lloyd’s heist on Ocracoke. Pirates, pirate hunters, treasure hunters, royal navies and many others were all on the lookout for the Lloyds. People sat around in aristocratic parlors of just about every country that ringed the Atlantic discussing the latest newspaper stories regarding the matter. Down on St. Kitts, where the silver was headed, well, the Lloyds practically became folk heroes.

There is a certain amount of irony in the fact that the author of “Treasure Island,” Robert Louis Stevenson, was born on Nov. 13, 1850, exactly 100 years to the day of the anniversary of Owen Lloyd, according to his own testimony, burying the treasure on Norman Island, a short sail from St. Kitts. But it is neither irony nor coincidence that the Stevenson family ran a sugar-production business on the island. It was here that one Alan Stevenson would arrive in 1773 to work for his uncle’s sugar business, where the legend of John and Owen Lloyd was still alive and well. Alan was Robert Louis Stevenson’s great-grandfather. The rest is history.

Learn More