HARLOWE — Gene Huntsman had to check the weather forecast before he’d agree to a date for an interview about his impending induction into the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, North Carolina’s top civilian honor.

“The first rule of retirement is not to do anything that interferes with fishing,” said the retired National Marine Fisheries Service biologist. “OK. Wednesday looks good. North wind, and maybe thunderstorms.”

Supporter Spotlight

It worked out just as planned; it was foggy, misty and cool that Wednesday morning, and Gene and Susan, his wife and fellow honoree, sat amiably and chatted happily for 90 minutes. But presumably, the weather won’t dictate whether the Huntsmans will show up for their induction ceremony, which is Sunday at 3 p.m. at The Train Depot in Morehead City. One thing is certain: they won’t have any trouble getting there, no matter what obstacles might be in the path; they are, in every sense of the word, trailblazers, and that’s precisely why they got nominated for the award by the Carteret County Wildlife Club and approved by Gov. Pat McCrory.

Bob Simpson, longtime club member and family friend, and for decades the state’s premier outdoor writer at the Raleigh News & Observer, put it this way in his nomination letter:

“Possibly the best known of their accomplishments would be their heroic efforts establishing the nationally recognized Neusiok hiking trail, 22-plus miles of public pathway pushing through seemingly impenetrable wilderness regions.”

Neusiok Trail

The trail, which runs from the Neuse River to the Newport River in the Croatan National Forest, was recently recognized by the state as an outstanding segment of the Mountains-to-the-Sea Trail.

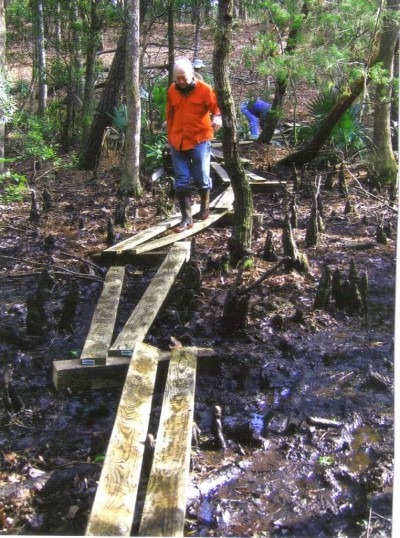

“Consider for a moment the effort required to find and create over 22 miles of trail,” Simpson continued in his letter, “convince associates to explore, mark and clear a pathway through dense forest laden with fallen trees, rotting logs, dead branches, dense entanglements of thorn-laden devils claw, assortments of vine, while being limited to the use of hand ax, saws and machetes, while relying on spinal and leg muscles and mud-laden, failing feet, while exploring potential routes through dark, dense forest, wading creeks, skirting swamp, seeking higher grounds, followed by the toting of timbers and bridging material before the actual construction could begin.”

Supporter Spotlight

Seated in their rustic home on a seven-acre plot of woods adjacent to the Croatan National Forest near Clubfoot Creek in Harlowe in Craven County, the Huntsmans insisted they weren’t heroic, but grudgingly acknowledged that the task was as difficult, in many places, as Simpson indicated.

“We mostly used machetes to hack through at first, and it was very slow going, very tough,” Susan recalled of the beginning of the effort, back in the early 1970s.

“We’d send Mary (Bob Simpson’s wife) out ahead with a compass reading and a flag attached to a tall stick, and she’d walk until we couldn’t see her, and then we’d chop to the flag, and then we’d do it again, and again.” Gene said.

Sometimes, Susan added, “We’d blow bugles to stay in touch. We did anything that worked.”

Susan often carried cooking supplies and food for miles to feed the hungry volunteer workers.

They and other Carteret Wildlife Club members toted lumber, thousands and thousands of two-by-sixes, for long stretches to form a stable path through the wettest areas.

They got grants from the state and from the American Hiking Association. They sought and received donations. It was a consuming passion. They convinced the forest service it was a worthy thing, necessary, important.

When bridges were needed to cross streams in areas too remote to get the lumber in by foot, the Huntsmans and the club somehow convinced the Marine Corps to fly tons of boards in by helicopter.

“They thought we were crazy when we asked them to do that,” Gene said. “They said, ‘No, no, no.’ But we talked to a colonel and eventually they agreed, and we are forever grateful.”

It took about five years, until 1976, to get the trail mostly complete, and the Huntsmans credit the National Forest Service for its cooperation and help. They also remember, however, when the forest service burned a couple of the shelters the club had built for hikers who wanted to rest or even spend the night.

“They were doing a controlled burn and they forgot they were there,” Gene recalled. “Whoops.

But they bought what we needed to rebuild them.”

Raving Success

Almost from its first opening, the Neusiok was a raving success. Susan said there are log books in the shelter signed by folks from all over the world, particularly Canada and Germany. Almost all are highly complimentary.

“It’s really a winter hiking trail,” Gene said. “When it’s too cold to do the Appalachian Trail, people come here. And it’s a great trail. It goes through every type of coastal habitat imaginable: salt marshes, cypress swamps, longleaf pine forests and pocosins. You can do the whole thing at once, but most don’t. It’s challenging, but not impossible for casual hikers. You can do a segment, just a nice afternoon in the forest. And the three shelters are spread out so you can just do one segment at a time. You don’t have to carry your whole house on your back.”

There is a source of water and a place to have a fire at each shelter.

The idea for the trail started, Gene said, when the son of a friend asked him about the best places to hike in the eastern part of the state. As members of the wildlife club since 1970, the Huntsman knew something about local trails.

“I remember I told him there were lots of nice logging roads to walk in the Croatan,” Gene said. “And he told me he didn’t want to walk on roads, he wanted to hike trails. And that’s when I realized that I didn’t think I’d been around a national forest that didn’t have hiking trails. So the club got involved and we started working with the forest service.”

The members did not, he said, have enough sense to think it was impossible. And it wasn’t. One of the goals was, of course, to simply provide a great trail in a national forest that badly needed one. But the ulterior motive, Gene admits, was always to get people out in the woods, to learn to appreciate them as the club members did, and to value them and the conservation values that are instilled simply by being in nature.

“That’s the real reason, in a nutshell,” he said.

Love of Nature

The Huntsmans came by this quest, well, naturally. Gene grew up in East St. Louis, on the Illinois side, and recalls spending lots of time outdoors as a boy, particularly after his father bought a farm in 1948. The family lived there for a time, and Gene’s love for the outdoors was forever cemented.

Susan was born and raised in England, where her family lived on 13 acres, and she was always fascinated by nature and drawn to the ocean.

They met while undergraduate students at Cornell University, Gene studying fisheries biology, Sue studying biochemistry. They got married in 1963. From there, both went to Iowa State University, where Gene earned his masters and Ph.D. in fishery biology. Susan got her Ph.D. in botany there.

But they knew they didn’t want to stay in Iowa. Gene recalls measuring, one winter, the ground frozen 36 inches deep. The toilet stopped working. It was not pleasant, even for grad students, who generally are accustomed to relative deprivation.

Eventually, they made their way to the University of Miami, where they studied marine biology at what is now the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. Florida wasn’t right for the couple either. Gene calls it boring. The weather was always the same, and it took too long to get anywhere else from Miami.

Gene had read The Old Man and the Boy, a classic Robert Ruark novel, first published in 1957, about growing up in the Southport area of North Carolina. Ruark, a journalist, author and hunter, made North Carolina seem like a good place to call home for outdoorsy types. The Huntsmans looked for jobs at the marine labs near Beaufort.

Gene ended up at NMFS on Pivers Island in Beaufort in 1967, working in its menhaden program and later heading up crucial reef fish work that eventually led to national efforts to save stocks of fish like snapper and grouper. Susan landed first at the Duke Marine Lab nearby, working with renowned oceanographer Richard Barber. Eventually, she moved to the NMFS lab. She specialized in trace metals in phytoplankton, the building block of much marine life. She’s also retired.

Ford “Bud” Cross, a former NMFS-Beaufort Lab director and a close friend, said the Huntsmans’ honors are richly deserved, even based only on the work they did at the lab.

Groundbreaking Work

Gene’s reef fish work was groundbreaking for the management of the species, Cross said. He combined surveys of head boats and recreational and commercial fishermen with analytics and fisheries population models. It had never been done before, Cross said, and has since been used by regional fisheries managers to develop plans to preserve and enhance the commercially and recreationally valuable species.

Susan, Cross said, did equally groundbreaking work to characterize the chemical speciation – when it’s toxic and when it’s not – of heavy metals in the water, such as copper. The idea was to determine the effects on phytoplankton and other marine organisms. “It was and is very important work that really changed the thinking,” he said.

Gene and Susan, 75 and 74 respectively, have lived in their Harlowe home since 1969. They have a couple of horses, lots of chickens, a year-round garden and two dogs, Pybr, a Welsh Springer spaniel, and Cadger, a Gordon setter. Both run happily outside but settle down peacefully at their owners’ sides in the house. It’s a picture of woodsy tranquility, with guns and all the other accoutrements of outdoor life on shelves and in nooks and crannies everywhere one looks.

Susan said Gene – true to his penchant for checking the weather before scheduling any lengthy indoor activity – can’t stand to be inside or any length of time. “He’s always in the garden, always, if he’s not out fishing or hunting,” she said.

Hunting remains one of Gene’s great joys. He likes woodcock hunting. It’s a challenge, he said, in part because they’re tiny birds. Susan isn’t so fond of eating them, though. But hunting is a big part of what led him and others in the Carteret County Wildlife Club to embark on creation of yet another Croatan National Forest hiking trail, the Weetock.

It’s basically a circle, close to 11 miles long. It begins (or ends) on N.C. 58 just south of the Hillfield Road, heads west for almost two miles on low bluffs along Hunters Creek, then proceeds mostly north, somewhat paralleling the White Oak River, for more than five miles to Haywood Landing. The last (or first) section traverses bluffs above Holston Creek about 3.5 miles east to the junction of N.C. 58 and the Haywood Landing Road.

It’s an area where Gene frequently hunted, and that’s when the idea hit him. “It’s much more open, not as dense as the Neusiok, and it was easy to envision a trail there,” Gene said. “Plus, it’s in an area that’s really growing in population, and there was a lot of demand for a trail.”

Again, too, there was that philosophical goal of simply getting people out in the woods, in nature’s glory, and to encourage them to be good stewards.

Gene still hikes, but he concedes he’s not quite as limber as he once was, and he also says he’s never been one of those “carry your house on your back” hikers. He’s always been more about making that possible, in the Croatan, for those who desire to take advantage of the opportunity.

He and Susan are still involved in the wildlife club, which also promotes hunting safety, and stay quite busy on their stunningly beautiful property.

Fun Life

It’s been a fun life, lived to the fullest, and while both defer credit for their accomplishments to the many who have helped, Gene and Susan both ended the interview with a quiet, partial retraction of their statements, at the outset of the talk, that they didn’t really know what they had done to deserve induction into the Order of the Long Leaf Pine. It’s an honor previously bestowed upon their great friend, Simpson.

“We certainly couldn’t have done any of this alone, by any means,” Gene said. “But I will say I’m proud that we all got it done.”

Simpson, in his nomination, also noted that the Huntsmans’ contributions to the state, nation and people also “include scores of other philanthropic works, including organizing the building and distribution of various forms of bird houses, including wood duck, owl and bluebird nesting sites, insect-devouring bat houses by the score, constructed by and sold at cost (and in demand) by assorted conservation organizations, garden clubs, scouting groups and individuals.

“Unselfish, honest, generous to a fault, selected as non-compensated consultants to several national and regional educational and conservation organizations, the Huntsmans have proven themselves among the most unselfish assets within this state and nation,” Simpson concluded.