This week may provide a glimpse into the future, a look at what our coast could be as sea level continues to inch up because of climate change.

All the planets will line up just right to produce “king tides,” the catchy moniker for highest tides of the year. They occur each fall and spring. The first ones this year will be Thursday through Sunday.

Supporter Spotlight

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is partnering with states and academics across the country in a citizens’ science effort – the King Tides Project – that’s encouraging people from all walks of life to go out during these tides and take photos, and sometimes measurements, and send the photos in to a Flickr account. It began in 2012 in Australia and has since spread around the world.

In North Carolina, the effort is through the UNC Institute of Marine Science in Morehead City. Christine “Chris” Voss, a research assistant, coordinates the work. It’s a part of a larger NOAA-funded research project on the ecological effects of sea-level rise, and she says it’s a natural fit. Voss, who works in the lab of Charles “Pete” Peterson, said the king tides project mostly just provides and seeks information.

“First, we just want to raise awareness,” she said. “We want people to be aware of what’s going on around them, to notice what’s happening. People know what happens in their neighborhoods far better than anyone else. Are there places where flooding occurs now where it didn’t occur in the past? Are there changes in the marshes? Do the floods happen more often?

One way to gather information is collect photographs of the flooding that the extreme high tides cause. “That’s what the project is about,” Voss said. “We want people to be safe when they do it – we don’t want them to take any chances – but we would love them to take these photos and send them in. It’s not difficult; almost everyone carries a cell phone with a camera these days.”

Supporter Spotlight

But the second goal of the project, Voss said, is to give people an awareness that what they see in these unusually high tides, caused by lunar cycles, is quite possibly what we might see as normal if sea-level rise continues, as most scientists believe it will.

The N.C. Coastal Resources Commission requested a 30-year forecast in 2015 after the General Assembly rejected a 2010, 100-year report that envisioned a 39-inch sea-level rise. Legislators shelved that report and passed a bill banning state planning for sea-level rise. The scaled-back 30-year report predicts as little as a two-inch rise along the southern coast to as much as 10 inches along the northern Outer Banks.

Regardless of what figures one uses, Voss said, it’s clear that more information is needed, and that the information gleaned from looking at “king tides” as a possible scenario for flooding as sea-level rise continues can help policy-makers. “We’ll make better decisions, do better planning, if we have more information about what could happen,” she said. “We need to know how we might have to adapt, what kinds of choices we might have to make. There might well be a time when we have to make hard choices about how we use our land differently.”

Flooding of streets and neighborhoods will likely get worse, she said, and will require careful planning to avoid. “We still have some time in these places, even very low areas like Down East Carteret County, to do that planning,” Voss said. “But it’s much better to look at what might happen than to close our eyes. And the concept is that the king tides project can help do that.”

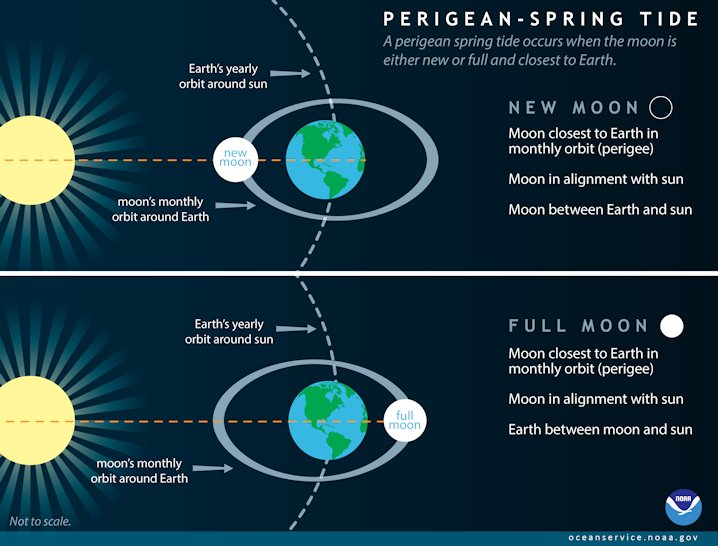

King tides are a normal occurrence once or twice every year when the alignment of the Earth, moon, and sun combine to produce the highest tides.

The last major floods in Carteret County occurred in October 2015, when those astronomically high king tides, combined with heavy rainfall and persistent onshore winds, flooded streets in Beaufort and Morehead City. Water levels rose two to four feet across Eastern North Carolina. On the northern Outer Banks, N.C. 12 was closed at Kitty Hawk because of ocean over wash and dune breaches. Many streets in and around downtown Columbia flooded, and water rescues were needed for people near Hobucken in Pamlico County. Charleston, S.C., had some of the highest water levels ever, even compared to hurricanes, and southeastern Florida neighborhoods flooded multiple times.

Voss said she doesn’t expect the king tides this week to be extraordinary. But the key word is “expect,” because these events in North Carolina are notoriously hard to predict. North Carolina extreme tides, she said, are driven more by wind than by lunar phases, and the prevailing southwest winds of late spring through summer can actually reduce tides rather than raise them. In fact, she said, some of the lowest tides in the state can happen in spring. But she’s interested in photos and measurements of those, too.

“I’m more interested in ‘interesting’ events than in just high tides,” she said. “One thing we hope to be able to do is look at measurements and photos and sees if we can match them up to meteorology.”

The goal, of course, is to increase predictability: If you can see what weather conditions do to these major tidal events, you can fine-tune predictions of what might occur, given the conditions, and fine-tune the actions that people might need to take.

Voss hopes people will get more involved in the king tides project. So far, she said, participation has been fair, but not what she’d like to see. It’s pure citizen science, at the grassroots level, she said, and people have a chance, if they participate, to make a difference.

“We want to be able to continue this effort for a long time,” she said. “Right now, it’s funded through 2018, but we’d like to see it last much longer.”

Greg “Rudi” Rudolph keeps tabs on tides – king and otherwise – as the manager of Carteret County’s Shore Protection Office, which is responsible, among other things, for monitoring the beaches and dunes and determining when and where beach nourishment projects are along Bogue Banks.

1

King tides can show us our future.

Like Voss, he doesn’t expect these king tides to be very extreme, but he also can’t be sure. With the April 7 new moon, he said, everything – Earth, moon and sun – “will be aligned as close as they can and in a straight line. If we have a storm on top of that, then that’s worse, but not the end of the world I would hope.”

He’s not so sure that it’s all that accurate to look at king tides as a precursor to the near-term future – this one is expected to be about a foot higher than usual – but he sees value in the project.

“That (one foot) would be a heck of a lot of sea-level rise,” he said. “The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an international group under the auspices of the United Nations) doesn’t have us reaching that much of rise until past 2050 in their worst scenario. However, this is where the nuisance flooding comes to play. A few inches more of sea-level rise and the king tides become more problematic.”

The research project will have value if it highlights those types of problems, Randolph said, and educates people about how weather affects the tides.

“If the project can also accentuate that it would be much worse if we have unfavorable weather conditions in addition to king tides – for example, a 35 mph northeast wind on April 5-7 – that’s also good,” he said. “If the project can demystify exactly what a king tide is, that’s good, too. It needs to be explained scientifically, so it’s not a mystery.”