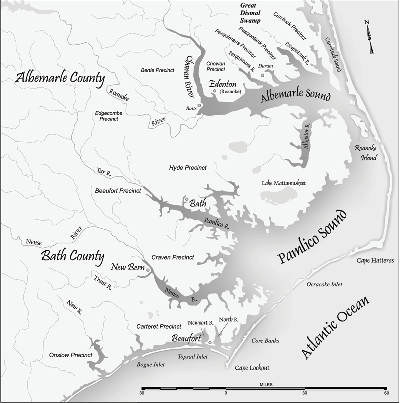

DUCK — North Carolina’s jutting elbow coastline is a distinctive feature on maps of the U.S. Atlantic coast. What is less obvious is that the vast amount of water behind those skinny barrier islands is the second-largest estuary in the lower 48 states. But somehow, comprehensive scientific analysis into the impacts of sea-level rise on that enormous system does not exist.

The Army Corps of Engineers has launched a $1.3 million research project in Currituck Sound to address the deficit of long-term data in understanding not only impacts of climate change on the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary, but also the multitude of environmental stresses compounding the estuary. The shallow, wind-driven Currituck Sound in the northeast corner of the coast flows into Albemarle Sound.

Supporter Spotlight

The corps installed five large monitoring platforms holding a range of instruments, including video cameras, in different locations in the sound to collect data on hydrodynamics, contaminants, nutrients, sediments, salinity, algae content, pH levels, wind and water temperature. Changes in seabed elevation and dimming of light as it moves through water – called “attenuation,” by scientists – will also be measured.

“The idea is to measure all kinds of physical and biological processes that go along the axis of the sound,” said Heidi Wadman, a research oceanographer at the corps’ Field Research Facility in Duck on the Currituck Banks. “It’s pretty unique. There’s no monitoring network like this in an estuary, in terms of scope, amount of data and the spatial set-up.”

The project, one of the largest single estuarine monitoring efforts in the nation, is seeking to fill gaps in data that was often inconsistently collected during numerous studies and research projects on the sound. Eventually, data trends will fill in blanks and answer questions.

A big impetus for the project, Wadman said, was the need to understand how to predict and mitigate the effects of rising seas and increasing storm surge on wetlands and sounds, where saltwater intrusion and shoreline erosion are already altering the ecosystem. There has also been increased turbidity and pollution that are changing the ecosystem.

“There’s no regular monitoring of shoreline position in Currituck Sound – or anything physical,” she said.

Supporter Spotlight

Little is understood about how sediment and water move through the sound and how the estuarine responds. “What are the waves doing? Are the contaminants coming downstream? What are the phytoplankton pollutants? How much and why?” Wadman asked.

A 2014 report by the U.S. Geological Survey, found numerous examples of gaps in data collection in the estuary related to water quality, submerged aquatic plants and physical factors. Politics, staff changes and budget cuts have conspired to limit the amount of information, the study noted.

“The negative impacts of sea-level rise may intensify other coastal hazards, such as flooding, storm surge, shoreline erosion, eutrophication, and shoreline recession, especially during extreme climatic events,” the report said. “Coastal managers need accurate information about the potential effects . . . to help plan and prepare for them.”

Wadman said that information collected from the platforms will be helpful immediately in understanding storm surge. But it will take 30 years, she said, to see trends that confirm accelerated sea-level rise.

A corps draft study of Currituck Sound in 2011 found worrying changes in salinity and water quality that had diminished the amount of submerged plants. After the last inlet in the banks closed in 1828, the sound became mostly freshwater, but polluted stormwater runoff has adversely affected wildlife and the ecosystem, the report notes. Though it was never made final, the report warned that without action there would be large losses of marshland, increased erosion, impaired water quality, decreased water clarity, increased algal blooms, wildlife habitat losses and greater amounts of invasive species.

The corps’ Duck pier station, on the Currituck Sound north of Duck, has conducted the longest-running coastal monitoring program anywhere in the world, Wadman said, but it focused on the ocean. The new monitoring platforms are designed to collect the same level of data on the sound.

“We’ve got the expertise,” she said. “There’s a need and there’s a gorgeous estuary right out our back door.”

Unlike previous studies of Currituck, this one will have longevity, Wadman said, because the corps intends to seek continued funding.

It also plans to make real-time data available to everyone, she said. Analyzed data will be posted hourly, probably starting in the summer, on the corps’ Duck pier website. The raw numbers will also be available by request, Wadman said.

“This is going to attract researchers from all over the world,” Wadman said. “Oh, yeah. An estuary like this? Definitely. The tricky thing is you have to measure it a long time to start to see the trends.”

Monitoring has been done for years by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency in the Chesapeake Bay, the nation’s largest estuary, but the Corps’ project, Wadman said, will use higher-resolution equipment, have more stations and collect more data. The goal is to install five more stations beyond Currituck Sound when money is available.

The five platforms – pilings, deck, solar panels and boxes containing the “brains” – have all been installed. Arms that extend up to 12 feet beyond the platforms will be added to hold the instruments. In the near future, Wadman said, cutting-edge instruments like a water level sensor that use microwaves and an acoustic fish tracker, will likely be added to platforms.

Robbie Fearn, director of the Donal C. O’Brien Jr. Audubon Sanctuary and Center in Corolla, helped organize in 2014 the Alliance to Restore Currituck Sound. A steering committee has held monthly meetings, and a community-wide session will be scheduled in the spring.

“I think it’s critically important to understanding the dynamics of the sound,” Fearn said of the corps’ project.

Fearn said that the data collected will be useful to nonprofit organization, government agencies and homeowners who live along the sound. “It will give us a full picture of the dynamics of that environment and what we need to do to care for it,” he said.

The Albermarle-Pamlico National Estuarine Project, funded by grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, has created a map of submerged plants in Currituck Sound and conducts diving surveys of the beds on a regular basis, said Director Bill Crowell.

Crowell said one of the goals of the partnership, of which the corps’ Duck Pier is a member, is to increase the research and study of the estuary, and he welcomes the corps monitoring project.

“We have a much greater need for data than exists right now,” he said. “The more they can gather, the better.”