First in a three-part series

WILMINGTON – There’s an old saying, “You don’t miss your water until the well runs dry.”

Supporter Spotlight

These days, the adage could be tweaked to also reflect the undesirable stuff that’s in the water – just ask the people in Flint, Mich., where the public water supply has become contaminated, the result of a government cost-savings measure.

Closer to home, drinking water sources have become contaminated by coal-ash ponds and illegally dumped chemicals, failing septic systems and, in many coastal areas, salinity drawn in when too much groundwater is pumped out. Sharp declines in the region’s groundwater levels have also grabbed attention.

More than three million N.C. residents rely on groundwater as their primary drinking-water supply. In the state’s coastal plain, 55 percent of the population depends on groundwater for drinking, according to the N.C. Cooperative Extension Service. More than four million N.C. residents rely on surface-water supplies, according to the state Division of Water Resources. Groundwater and surface water are connected.

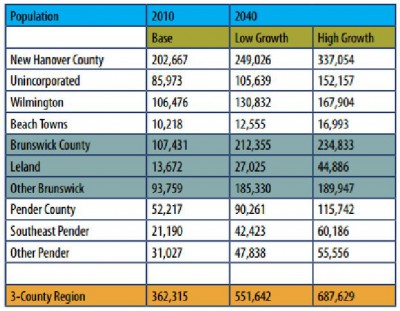

Climate change and sea-level rise, along with what some describe as explosive population growth, industrial development and other changes on the N.C. coast, could make freshwater availability and competition for the water rights a big issue in the years ahead. Here in the fast-growing southeastern part of the state, demands on water resources, both surface water and groundwater, are prompting officials to look at new ways of dealing with the problem over the long term. Their worries aren’t based on theories or predictions, fights over water rights have already begun.

Triangle communities, including Cary and Wake County, obtained permission in 2015 to draw increased amounts of water – tens of millions more gallons a day – from Jordan Lake, a reservoir at the headwaters of the Cape Fear River. Downriver, officials in Fayetteville and Wilmington, both of which get much of their drinking water from the Cape Fear, opposed the decision. The dispute prompted lawmakers to mandate a study of water resources across the entire Cape Fear River basin to identify these conflicts and avoid or minimize them in the future.

Supporter Spotlight

“Making sure that we’ve got sustainable and safe water in North Carolina is extremely important for our future and for our present citizens,” said Rep. Rick Catlin, R-New Hanover, who introduced the Cape Fear Water Resources Availability Study bill that was passed last year.

Catlin is a hydrogeologist by profession. He doesn’t plan to seek re-election when his term ends this year. The decision to focus on his business doesn’t mean Catlin’s involvement in water issues will end when he leaves office.

“I’ll continue to work on that even after I’m no longer an elected official,” Catlin said. “I know how important it is to make sure we don’t run out of water and that we don’t have contamination.”

In addition to municipal demands for water resources, large-scale industrial water users have long been known to have significant effects on water supplies. Demands for water are increasing from commercial, industrial, mining, irrigation and other sectors, according to government reports.

Some say plans to expand a mining and cement-manufacturing facility near Castle Hayne in New Hanover County could have negative effects on groundwater and surface water resources in the region, although officials with Titan-America, the company behind the plans, and others dispute those claims.

The project will require the excavation of an open pit adjacent to the Northeast Cape Fear River in order to extract and process the raw materials, calcium carbonate and limestone, for producing Portland cement. The process will require pumping about four million gallons of groundwater a day to allow dry-pit mining as planned, according to the company. Environmental groups, including the N.C. Coastal Federation, contend the amount could be four times the amount the company claims and that this dewatering process is a threat to regional groundwater supplies. Titan says no effects on groundwater are anticipated to affect groundwater quality.

“We’ve had no wells go dry and we’ve been mining here almost 50 years,” said Bob Odom, general manager at Carolinas Cement Co., Titan’s local subsidiary. “We’ve seen nothing negative.”

Catlin remains skeptical.“It will have an impact on the water wells in the northern part of New Hanover County,” he said.

We’ll take a close look at Titan’s groundwater discharge in the last part of this series.

Contamination on the N.C. Coast

Evidence emerged in 2010 that coal ash ponds at Duke Energy’s Sutton Steam Plant near Wilmington were contaminating groundwater. The Wilmington plant is just one example – more than 85 percent of drinking water wells tested near the 14 Duke Energy coal ash sites in North Carolina are contaminated and unsafe for cooking or drinking, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Duke Energy was fined in 2015 and ordered to clean up the coal-ash mess here and at its other N.C. facilities but the cleanup has been slow going. Soon after the state announced in March the $25 million fine, which was ultimately reduced, Tom Reeder, North Carolina’s assistant secretary for the environment, said in court filings that the penalties should have been bigger. “They’ve nuked this whole drinking water source for the Wilmington area,” Reeder said at the time.

Just up the coast, decades of water contamination at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune exposed more than 750,000 Marines and their families to chemical toxins at alarming concentrations, as base officials refused for years to acknowledge the problem. People living or working there from 1953 to 1987 were potentially exposed to drinking water contaminated with benzene, and other toxic chemicals used for industrial cleaning, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. A 2014 study showed links between the contamination and higher incidences of death from cancer and other diseases. Previous studies had raised similar concerns. Victims accuse Marine Corps leaders of years of inaction.

Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., pressured the Veterans Administration for assistance to veterans sickened by the water at the base. The VA announced in August that new regulations may allow some veterans to receive disability pay if they were sickened by drinking contaminated water at Camp Lejeune.

“The scientific research is strong and the widespread denials of benefits will soon end. Now these veterans and their family members will not have to fight for benefits they are due,” Burr said at the time.

Saltwater Intrusion

Increasing demands on groundwater supplies are causing saltwater to be drawn into freshwater aquifers in a number of coastal areas, yet another contamination threat to what many have long considered an imperiled resource.

Research shows the proposed deepening of the shipping channel that serves the N.C. Port of Wilmington has the potential to alter nearby groundwater flow and potentially allow a direct pathway for saltwater intrusion.

Even private, residential irrigation wells can have an effect. “That has actually caused some saltwater-intrusion problems,” Catlin said.

Catlin said rising rates for water from the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority prompted many homeowners in his district to put in private irrigation wells to save money. Legislation he sponsored directs the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to study data on irrigation wells so the extent of their effects can be better understood.

“I found out that they were required to submit data on irrigation wells and they have not been doing that,” Catlin said. “DEQ has that data but hadn’t used it, so now we’ll have a lot more information on aquifer usage.”

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Richard Spruill is an associate professor of hydrology at East Carolina University. Spruill said the complex aquifer systems that underlie the coastal plain are tapped extensively by municipalities, industries, agriculture and individuals, creating lots of problems.

“The biggest challenge seems to be a fair and equitable allocation of water resources based on regional differences in the resource itself,” Spruill said.

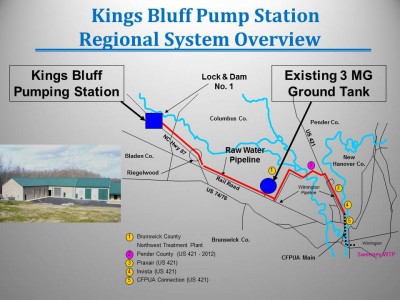

Few cities across North Carolina’s coastal plain take their drinking water supply from surface water. Greenville draws from the Tar River; Kinston, which is a partner with several neighboring small towns as members of the Neuse Regional Water and Sewer Authority, draws from the Neuse River; and Wilmington relies on a combination of the Cape Fear River and groundwater supplies.

“Everybody else throughout the coastal plain is using groundwater,” Spruill said.

For surface water-dependent communities, the biggest issue is drought and how that relates to flows in their respective river systems. For those relying on groundwater, the concern is often other big users. Operations in this region that pump water from the ground face little regulation covering the effects on other users.

The big difference is, that with groundwater supplies, the resource is more likely to be mismanaged. Spruill said that’s the case across the coastal plain and beyond, up and down the East Coast.

“We don’t address it because it’s out of sight, out of mind. It’s different from our river system,” he said.

Coastal Population Growth

The steady population growth in coastal areas means more long-term use of groundwater in places where demand was previously more seasonal in nature. Beach towns that were once sleepy during the winter months have grown now that more people are choosing to live there year-round.

“As more and more people move to these locations the demand is higher and higher all year long so the aquifer doesn’t have time to recover,” Spruill said.

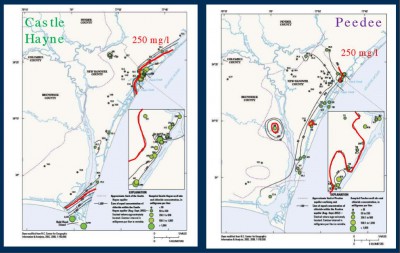

A recent U.S. Geological Survey study showed evidence of potential problems. Samples collected in 2012 from 97 well sites in Brunswick, New Hanover and Pender counties show saltwater intrusion has moved landward since the mid-1960s. The saltwater-freshwater interface in the Castle Hayne aquifer has crept about a mile inland in northeastern New Hanover County. It’s also a problem in the Peedee aquifer near Carolina Beach at the southern end of the county.

Spruill said a new attitude is needed.

“We seem willing to mismanage the freshwater groundwater supplies until they go salty. Is that the right thing to do or should we reduce use until we can bring it in to balance so it doesn’t go salty? We should not mismanage our fresh groundwater systems in such a way as they become salty simply because we have technology to treat the saltwater when it comes,” Spruill said.

What areas are at the greatest risk and what are the timeframes involved? There’s no clear answer, Spruill said.

“We don’t know enough about the position of the fresh water-saltwater interface to predict when it’s going become a problem in the coastal plain,” he said. “I can tell you it’s occurring at lots of different places in North Carolina and South Carolina.”

Saltwater intrusion required construction of a reverse-osmosis treatment plant in Emerald Isle at the west end of Bogue Banks. The plant went online in February 2013. The process is effective but more expensive than standard treatment. It takes 10 gallons of saltwater to produce seven to eight gallons of freshwater, with about two gallons of wastewater that is pumped into Bogue Sound.

Seola Hill is director of Bogue Banks Water Corp., which operates the Emerald Isle plant. He said that before building the plant, several of the corporation’s wells on the west end of Bogue Banks were approaching or exceeding the state’s maximum chloride count of 250 parts per million, the measure of saltwater intrusion.

“There was also a secondary reason, other easterly wells were also showing higher chloride levels and the problem was growing over time,” Hill said. “as a long-term solution, we built a high-capacity reverse-osmosis plant to see if we can keep that saltwater intrusion from migrating. We theorized that the water was migrating from west to east in our area and by over-pumping we could keep the migration of saltwater localized. It’s actually done that. It’s worked really well.”

The reliance on reverse osmosis will likely grow, Spruill said. “It will become an increasingly important problem in coastal areas,” he said. “Salty water exists in the Castle Hayne aquifer as far inland as Elizabeth City.”

In addition to Elizabeth City, Outer Banks communities including Rodanthe, Waves, Salvo and Ocracoke Village rely on reverse osmosis. To the south, Figure Eight Island has also seen some saltwater intrusion.

“We’re in a situation where we have to plan ahead. The cost of quality water will go up,” Spruill said. “There’s enough groundwater to meet Wilmington’s needs now and in the future but most of it is salty. That will require new sites for new wells and reverse-osmosis plants and there is some impact from discharging salty water into an estuarine environment.”

Part II: Researchers Focus on Groundwater

Part III: Groundwater: Gauging the Titan Effect