BEAUFORT – Living shorelines have been given a national stamp of approval in a new federal report that encourages a natural approach to managing coastal erosion.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s “Guidance for Considering the Use of Living Shorelines” explains the agency’s stance on natural bank stabilization methods, why living shorelines are a preferable alternative to hardened structures, and NOAA’s role in helping property owners who want to build a living shoreline.

Supporter Spotlight

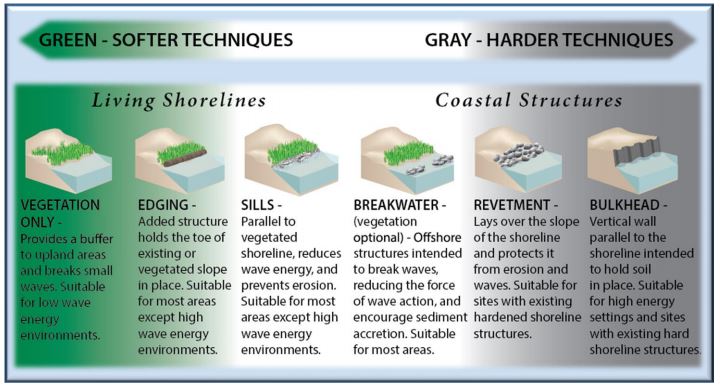

While NOAA’s guide makes clear that living shorelines are not suitable in all areas, particularly shores within high wave action zones, the agency points to several benefits associated with natural shoreline projects.

This is the latest in a mounting chain of evidence that living shorelines hold up better through storms than hardened structures, enhance intertidal habitat for fish and other marine resources, and better defend properties against sea level rise.

But even as living shorelines are gaining more attention on a national scale, bulkheads and seawalls widely remain the popular choice among waterfront property owners.

In North Carolina only a handful of permit applications for living shorelines are submitted to the state each year. Part of the reason for the low numbers is that more public education about natural shoreline stabilization techniques is needed, experts say.

Then there is the permitting process.

Supporter Spotlight

Bulkhead permits in many cases are issued within a matter of a few days. The permitting process for living shorelines can take months. But documents such as the NOAA guide could reshape the national permitting process.

Though there is a general permit for living shorelines in North Carolina, most applicants apply for a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit.

The way the system is set up now, general permit applicants have to go through the N.C. Division of Coastal Management. Applications have to be reviewed by the state Division of Water Resources and N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries. Applicants must then go to the Army Corps of Engineers for authorization.

“That’s putting the burden on the applicant,” said Daniel Govoni, a Division of Coastal Management policy analyst. “The major permit process, because staff will do that for you, is pretty much an easier route for the applicant.”

The Corps’ regional general permit 291 covers shoreline projects in or affecting navigable waters.

While bulkhead permits are typically done within a week, the CAMA major permit for living shorelines takes 45 days “or a few weeks longer,” Govoni said.

There are a couple of reasons why the review process for living shorelines is lengthier than bulkheads, said Dale Beter, supervisor of the Corps’ Wilmington Regulatory Field Office.

Living shorelines projects are usually located in navigable waters and, unlike seawalls, which abruptly abut the shore, natural stabilization projects span out into the water.

They may also affect essential fish habitat, areas of which are protected under federal law.

Breaking down the land-to-water barrier

In some cases living shorelines can convert existing habitat to another type of habitat.

NOAA’s guide refers to this as a trade-off, where, for example, planting a marsh in open, shallow water changes the habitat. NOAA emphasizes living shoreline projects should minimize aquatic habitat displacement and the loss of essential fish habitat and endangered species critical habitat.

This is still the better environmental alternative to bulkheads and other hardened structures, which essentially remove shallow water habitat.

“We have shown that living shorelines are resilient, but they are not drawing a line in the sand,” said Carolyn Currin, a microbiologist with the NOAA laboratory in Beaufort. “The problem with walling off is it really is walling off that estuary. When you wall off the estuary all of a sudden that shallow water habitat is gone.”

That habitat is critical for fish larvae, which seek refuge in shallow water to survive through their juvenile stage.

If hardened shoreline structures remain the status quo and the coastal population continues to grow, nearly one third of the nation’s contiguous shoreline is expected to be hardened by 2100, according to the NOAA guide.

“There is evidence that shorelines having intact natural coastal habitats (e.g., wetlands, dunes, mangroves, and coral reefs) experience less damage from severe storms and are more resilient than hardened shorelines,” according to the document.

This is particularly important as coastal storms increase in intensity and sea levels rise. Research is finding that living shorelines are able to keep up with sea level rise.

“What we have found over time is that many of the salt marshes, they’re actually adding to their elevation on the order of 2 to 4 millimeters per year, which is the current local rate of sea level rise approximately,” Currin said.

Oyster reefs also grow upward with rising seas, maintaining mean sea level elevation.

“None of us knows exactly what’s going to happen with sea level rise,” Currin said. “The problem is that we are anticipating an accelerated rate. Marshes will be able to keep up with that to a point.”

Neither a living shoreline nor a bulkhead can protect property from, say, an eight-foot surge. But a natural marsh may slow the passage of storm surge while water will simply spill over a bulkhead. These are things for property owners to keep in mind, said Lexia Weaver, a coastal scientist with the N.C. Coastal Federation.

“Not only are you protecting your shore from erosion, but you’re providing habitat essential to things like fish and oysters and that, in turn, helps the local economy,” she said.

Bridging the permit gap

There is no one-size-fits-all design for living shoreline projects. What works well in one region may not in another part of the country.

“That is the reality and that is the difficulty,” Currin said. “You’re putting together a system that needs to work, but there isn’t a cookie-cutter design although we’re getting closer and closer at coming up with some design criteria. I think we’re getting closer to coming up with some very specific guidelines.”

In the meantime, state agencies, including the N.C. Division of Coastal Management, are working on ways to streamline the living shorelines permitting process.

Govoni is set to present amendments to the current general permit process during the upcoming N.C. Coastal Resources Commission meeting Nov. 17-18 in Atlantic Beach. The division proposes to remove state fisheries and water resources coordination requirements.

“If they OK it we’ll go forward with the rulemaking changes to have those conditions removed from the permit,” Govoni said. “It would shorten the amount of time for the permit to be issued.”

The idea is not necessarily to substantially shorten the time it takes to issue a permit for a living shoreline project, but rather to level the playing field by lengthening the review process for bulkheads.

“To have a 30- to 50-day review period on something that could impact the public trust resources I don’t think is a problem,” Currin said. “My personal opinion is that the problem is that it only takes three days to get a bulkhead approved. I think the bulkhead review needs to be a much longer period.”

The Corps will begin next year reviewing its nationwide permitting program, a process done every five years. During the review process it’s not uncommon for the Corps to revoke, modify and create new permits, Beter said.

“The Corps is neither a proponent or an opponent of any project,” he said. “For us to come up with general permits or things like that there has to be a considerable need. In past discussions about performing a district-specific marsh sill or general permit, we don’t deal with the numbers currently that we think would warrant that. I think there’s a lot more awareness out there, but we’re not talking hundreds here. We’re talking about a few.”

Interest on a national level may prompt the Corps to make changes, giving districts the opportunity to tailor new or modified permits to their regional areas. The public will have an opportunity to review and comment on proposed rules and statutory changes.