Reprinted from N.C. Health News

WILMINGTON — Thick black smoke hovered in the autumn skies over Wilmington 153 years ago this week. Carts collecting dead bodies trundled over the roads and uncollected rubbish produced a stench that permeated the city.

Supporter Spotlight

Gravediggers at Oakdale Cemetery, just outside of town, buried at least a dozen bodies a day. Half of the city’s 10,000 residents had fled to the homes of friends and relatives. But the ones without means or a destination huddled behind to wait out the plague, along with those who served them as physicians, caregivers and tenders of the dead.

During the end of the week of Oct. 17, 1862, 453 Wilmingtonians came down with yellow fever. The following week, 111 died, making it the most deadly week of the epidemic.

Supporter Spotlight

Overall, between late August and the first frost in November, 1,505 people contracted the disease; of those, 654 died.

Yellow fever, a “hemorrhagic” fever, similar to the Ebola virus disease, starts innocuously with a fever, chills and diarrhea. But within days, bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract produces black diarrhea and vomit, along with abdominal pain, as can Ebola. In the final throes, patients begin to bleed from the gums, nose and bowels.

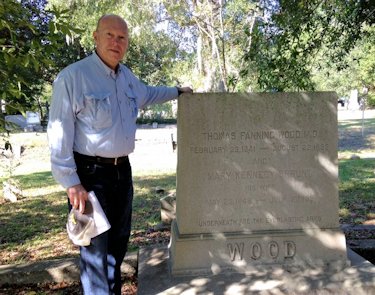

The similarities between yellow fever and Ebola have not been lost on David Rice, the New Hanover County health director, who on occasion leads groups of people on tours through Oakdale cemetery. He is also an amateur historian of health care in North Carolina.

Rice said he thought about the panic, fear, superstition and stigma that accompanied the arrival of yellow fever as he’s prepared his community last year for the possibility of a case of Ebola.

Entire Families Killed

Rice said no one is really sure how the yellow fever epidemic started. It might have arrived on a blockade runner or another ship with a sick crew. As the city was also in the throes of the Civil War, many whispered that Union soldiers had snuck a sick patient into the city – a 19th-century accusation of bioterrorism.

What is certain is that the summer of 1862 had been rainy, leaving many ponds and flooded areas where yellow fever carrying mosquitoes could breed. But at that time, people were unaware that this was how the disease spread. Food was scarce because of the war, people were undernourished and many of those usually tasked with keeping the streets cleaned and encroaching water at bay were off fighting.

Some stayed behind, and their job became one of collecting bodies, as recorded by epidemic survivor John Dillard Bellamy, who was 8 years old at the time.

“I recollect, well, having stood in our home on Market and Fifth Streets, watching wagon-loads of corpses go by to Oakdale Cemetery,” he said.

Those manning the “death carts” retrieved bodies from the terrified families of the deceased, said Eric Kozen, superintendent of Oakdale. At the time, people did not know how yellow fever was transmitted and did not want to keep the bodies inside their homes, for fear of contagion, so bodies were left by the side of the road. Whole families died, one after the other.

For more than 400 of those bodies, their final resting place was a mass burial ground on a high point in Oakdale.

“As bodies were being brought here to the cemetery, we were receiving anywhere from about 10 to 15 a day during the height of the epidemic,” along with those who died of other causes, Kozen said.

They were not mass burials, with a one pit receiving dozens of bodies; instead, they were methodically done in 28 rows, each 20 to 30 yards long. One is simply marked “children.”

“The husband would die; he would be buried in a certain gravesite. His wife would pass, sometimes three days later. They would open that same grave, bury her with him. Children would follow thereafter. So we actually had up to four or five people being buried in the same grave in a month’s time frame,” Kozen said. “It would wipe out entire families.”

In the push to get bodies interred, few gravestones were erected. Instead, what remains is a field punctuated by stately oaks, camellias and azaleas, and, since Kozen’s arrival, thousands of daffodils in the spring.

“It was pretty scary stuff,” Kozen said. No one knew how the disease got around or the best way to handle the sick and the dead.

“That’s where that whole public fear came in, and that’s why cemeteries were developed on the edges of towns.”

Fallen Caregivers

As with the Ebola epidemic, many health care workers who fought yellow fever became victims. They’re also buried at Oakdale, along with those they cared for.

The brilliant Dr. James Henderson Dickson reported the very first cases of yellow fever on Sept. 17, 1862 to state officials.

“Since Tuesday the 9th, I have seen five cases of the disease,” he wrote. “Of these, two have died, one is discharged as a convalescent, and two are still under treatment with doubtful prospects.”

Dickson’s friend John Lamb Pritchard, pastor of First Baptist Church, asked Dickson whether he should visit a sick patient. From an account read by Rice, Dickson told his friend, “‘I reckon you will have to do as I do. It is like war, we must have to take our chances. You will have to go and see many during their illness.’”

Rice read from an account of Dickson’s final patient visit. The doctor stood in the door, propping himself up on the doorposts as he advised his patient.

“‘I cannot come in. I have the fever now,’” Rice read.

By the end of September, Dickson was dead.

Rev. Pritchard sent his family from town, but remained to tend to his remaining flock. Rice read from his diary, where he wrote, “‘Must a minister fly from disease and danger and leave poor people to suffer for want of attention? Did the Saviour ever draw back?’”

Pritchard too died of yellow fever, along with his colleague Robert Drane, the rector of St. James Episcopal. Drane’s sister, who remained to help him, died as well.

“Someone asked, why did they remain?” Rice said. “Well, we have duties; we can’t abandon our duties.”

One of those who stayed was Phineas Fanning, who supervised collection of the dead, provided “subsistence for the destitute who could not flee” and oversaw protection of abandoned property. Fanning also took over operations of the cemetery after the superintendent, James Quigley, died in the middle of the epidemic. Rice said Fanning himself was left destitute by the end of the Civil War.

Echoes Sound Today

The epidemic served to galvanize many of Wilmington’s leaders to work against a repeat of the horror.

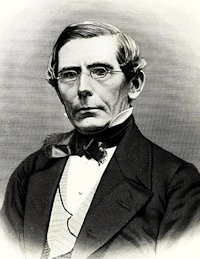

Physician Thomas Fanning Wood survived because he was away, serving as a Confederate surgeon. Rice noted that Wood lost his wife and family to infectious disease and “he saw injury and illness, and he didn’t want our communities facing that in the future.”

Now Wood is known as the “father of public health” in North Carolina.

“He went back and forth to the legislature begging them to start the public-health movement, and they finally gave in to him because he was so persistent,” Rice said, noting that the General Assembly gave Wood a mere $100 to get the state’s public-health service started.

Rice has quipped that public health remains underfunded.

Another Confederate surgeon, Solomon Sampson Satchwell, became the first president of the N.C. Medical Society. Wood started the N.C. Medical Journal.

And although Rice does tours of the cemetery for the Friends of Oakdale, his day job has had him consumed with Ebola preparedness for weeks in the fall of 2014. He said he had numerous panicked calls about Ebola to his office.

But he expressed greater concern for rabies in his area than Ebola. And he urged people on the tour to get vaccinated against the flu.

Every generation, it seems, has a dread disease to be faced by patients, caregivers and the public, he said.

“It’s the same as yellow fever. You have to learn about the diseases, you have to contain them, you have to stop them.… Same thing with Ebola; you have to educate and contain,” he said.

To prepare, Rice recently convened all local officials who might have had anything to do with Ebola response, from airports and ports to schools to hospitals. He also convened a media-education session.

“My thought is that we haven’t had to respond to a hurricane, let’s respond to a hurricane-like condition called Ebola,” he said.

And Rice said the historian in him was continually making connections between Ebola and yellow fever.

“If you don’t visit the history of what has occurred, you’re apt to repeat it,” he said. “We try to make those connections from the past so we can better serve in the future.”

To Learn More

- Oakdale Cemetery, the oldest rural cemetery in North Carolina

- City of the Dead: Wilmington’s Yellow Fever Epidemic