Everyone is, of course, welcomed at beaches along the N.C. coast. They are free to choose where they will shop, dine, lodge or bask in the sun. That wasn’t true not too long ago.

For almost a century, from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, blacks in America couldn’t just go to the beach for their summer vacation because of —particularly here in the South—that enforced racial segregation. Signs that read “White” or “Colored” were seen on storefronts, in waiting rooms, on restroom doors, above water fountains and at other places.

Supporter Spotlight

Flora Hatley Wadelington, in her article “Assigned Places” that appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Tar Heel Junior Historian, wrote “North Carolina, like most southern states in the 1920s was rigidly segregated … African-Americans across the state, from cities and towns to rural areas, endured a system of segregation while building their own institutions.”

The state’s beaches were no exceptions. There were little to no oceanfront offerings for African- Americans. Although a few beach communities were developed exclusively for African-American use during the 1920s—particularly Asbury Beach on Atlantic Beach and Shell Island near Wrightsville Beach—they were all short-lived.

Blacks were no doubt disheartened by the lack of an accessible seaside resort. Where in North Carolina would they be welcome to swim, relax and enjoy the cool ocean breezes? A large parcel of earth, just north of Carolina Beach in Hanover County, provided the answer. Facing Myrtle Grove Sound, the land destined to become Seabreeze—a resort created by and for blacks—was already rich in African-American history.

It started when Alexander and Charity Freeman, a free black couple, bought 180 acres along Myrtle Grove Sound, according to Andrew W. Kahrl in his book The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South. Their son, Robert, bought more land after the Civil War. When he died in 1902, Robert Bruce Freeman left more than 5,000 acres to his 11 children, writes Kahrl.

The land was generous and provided a host of resources—such as fishing, farming and logging—from which to earn a living. Yet, by 1920, some members of the Freeman family thought more money could be made by selling or developing their waterfront holdings. Kahrl documents that two of Robert Bruce Freeman’s children, who owned clear title to 65 acres, formed the North State Realty and Investment Co. in 1922 and divided their land into small lots for sale. What became Seabreeze soon followed.

Supporter Spotlight

Victoria Lofton, a prominent African-American woman from Wilmington, was one of the first developers to buy a lot. In 1924, she opened a three-story, 25-room hotel that included a restaurant, dance hall, fishing pier and cement walkway to the beach.

News of the resort spread quickly and it wasn’t long before Lofton’s hotel rooms—and the streets of Seabreeze—were overflowing. As the number of blacks coming to Seabreeze grew, so did the resort community. In all, Seabreeze was home to numerous hotels, a row of beach cottages, various restaurants, 31 “juke joints” — places where people listened and danced to music — private residences and an amusement park.

The ocean breezes that blew through Seabreeze were no doubt infused with the smell of palate-pleasing dishes. Restaurants in Seabreeze served a diverse selection of food, but were renowned for their fresh, local seafood. No meal, however, could compete with Sadie Wade’s clam fritters. Made from a “secret recipe,” Wade’s fritters were hailed as the “world’s best.”

A small amusement park in Seabreeze must have echoed with sounds of laughter, as people enjoyed various rides and curiosities. Operated by a Native American known as “Snakeman,” the carnival featured a Ferris wheel, a carousel, games and of course snakes. Onsite photographers and photo booths captured the fun and created lasting souvenirs.

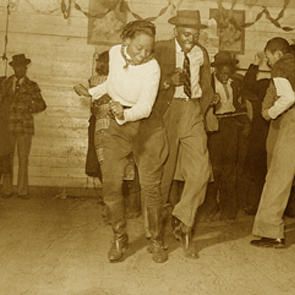

The heartbeat of Seabreeze was its many juke joints. Those who vacationed there remember them well. Booker T. Wilson, who lives in Bolton, visited Seabreeze regularly as a young man. When asked what he remembered most about the place, Wilson promptly replied, “The dancing!” His favorite style of dance? “Swing. All of it,” he said.

The music of Seabreeze traveled for miles, as live bands and jukeboxes exploded with the sounds of swing, soul and rhythm and blues. Feet—brought to life by the voices of Little Richard, James Brown, The Platters and others—pounded and shuffled across wooden dance floors. Ben Steelman, in his May 6, 2009, Wilmington Star-News article, wrote “By the 1940s—when thousands of black GIs flocked to Seabreeze from nearby bases—the area became known as a music mecca.”

In addition to an influx of African-American servicemen, white teenagers were also venturing to Seabreeze. As reported by Steelman, “White kids from nearby Carolina Beach, such as Malcolm “Chicken” Hicks, would cross over to check out Seabreeze’s night spots and the local dance steps. Local historians, such as Jenny Edwards—who wrote a master’s thesis on the history of Seabreeze for the University of North Carolina Wilmington—credit this musical cross-pollination with promoting, if not inspiring, the later crazes of shag dancing and beach music.”

Beyond its mainland diversions, Seabreeze also provided African-Americans access to the Atlantic Ocean. Across from Seabreeze and the Myrtle Grove Sound lies the northern tip of Carolina Beach. Belonging to heirs of Robert Bruce Freeman, the pristine, undeveloped shore was appropriately named Freeman Beach. The oceanfront property was developed in 1951, when Freeman’s daughter Lulu and husband, Frank Hill, opened Monte Carlo by the Sea. According to Kahrl, their hotel was “a gleaming, white cement structure, replete with a dining room covered in seascape murals that doubled as a dance hall, locker rooms, showers, kitchen and takeout window, facing the Atlantic Ocean.”

Frequented by local and national recording stars, Freeman Beach became known as “Bop City.” However, getting to “Bop City” had its challenges. In the 1920s, blacks were able to wade or swim across Myrtle Grove Sound to reach Freeman Beach. But, in 1931, Snow’s Cut—an artificial canal which connected the Cape Fear River to Myrtle Grove Sound—was completed. As a result, the depth and current of Myrtle Grove Sound changed drastically, which made wading or swimming to the beach impossible. African-Americans now had to drive through segregated Carolina Beach to access Freeman Beach or hire someone with a boat to ferry them over.

Snow’s Cut proved devastating to Seabreeze, polluting Myrtle Grove Sound and increasing erosion. Land flooded and fish and other marine life died because of the inflow of contaminated freshwater. When the Carolina Beach Inlet was cut in 1952, it had a similar effect on Freeman Beach. “By the 1970s,” wrote Kahrl, “the initial one-hundred-foot wide inlet had, as a result of erosion, widened to seven hundred feet.”

Juke joints like this one were the most popular spots in Seabreeze. This video was shot in 1947.

While man-made changes worked at a steady pace to reshape the environment around Seabreeze and Freeman Beach, a swift, terrifying and natural force took form in the Atlantic Ocean. On Oct. 15, 1954, Hurricane Hazel—the only Category 4 hurricane to hit the N.C. coast—made landfall near the North Carolina-South Carolina border. In a moment of fury, Hazel cast Monte Carlo by the Sea into a watery abyss and blew Seabreeze into ruin.

When the storm departed, residents and property owners were tasked with cleaning, clearing and rebuilding. People who held land in common with other relatives found the job particularly daunting, as they were deemed ineligible for disaster relief loans. Without financial assistance, many could not afford to rebuild. Those who were able, however, worked hard to bring Seabreeze back to life. Music, food and laughter did return; but the Seabreeze that once was would be no more.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 further contributed to the demise of Seabreeze. African-Americans could vacation and partake of recreation wherever they desired, and Seabreeze—which had been a shelter in the storm of segregation—was no longer needed. A few businesses in Seabreeze held on, but by 1975, most had closed their doors.

As the years progressed, disputes over land ownership, further destruction by hurricanes and continued changes in the land left Seabreeze neglected and deteriorated.

Nevertheless, the winds now blowing through Seabreeze appear to be moving in a positive direction. New and renewed interest in the history and preservation of Seabreeze has had several recent outcomes, including the production of Rhonda Bellamy’s documentary film A Sense of Place that chronicles the changing history in Seabreeze, Zach Hanner’s dinner show Summers at Seabreeze, which celebrated the community through song, stories and dance and the addition of Seabreeze to the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. The Corridor recognizes places associated with the culture and history of African-Americans, known as Gullah Geechee, who settled in the coastal counties of South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina and Florida.

As a heritage area, Seabreeze will no doubt garner needed support for the study and preservation of its land, history, and coastal traditions.

An article about Seabreeze was published on the website ncbeaches.com. In the last sentence the author proclaims, “Put your ear to the ground and you’ll no doubt hear that heavy bass beat still reverberating in the sand.” How appropriate. The unique history that is Seabreeze remains alive through memories and is being told, preserved—and heard.