SMYRNA — Penny Hooper of Smyrna in eastern Carteret County wasn’t supposed to go to the Aug. 11 Morehead City Council meeting, at which a resolution to oppose offshore oil drilling was on the agenda.

She’d had hip replacement surgery earlier in the summer, and she was one of the unlucky one percent who emerge from that operation with a broken femur.

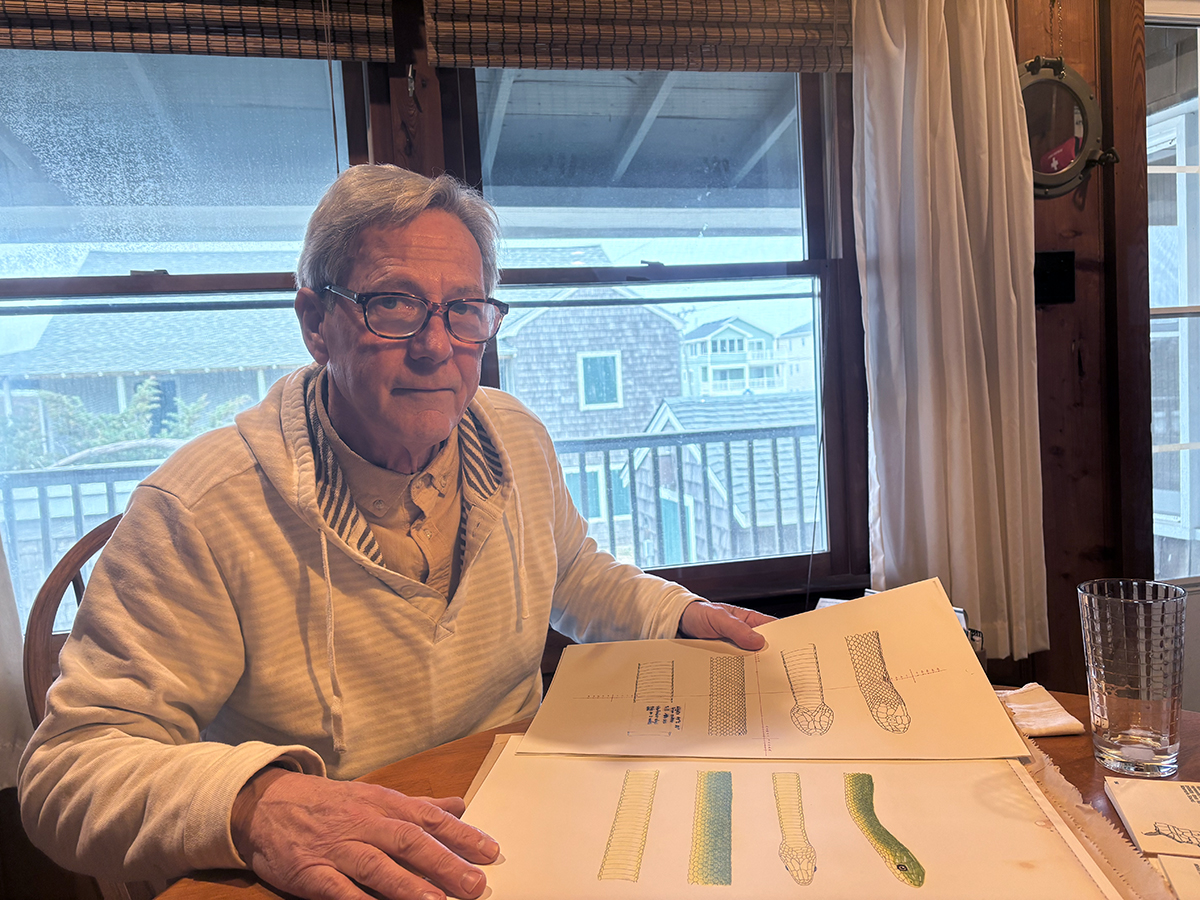

Supporter Spotlight

“I was in physical therapy, three times a week, for five weeks,” she said recently. “The therapist said I couldn’t put any weight on the leg. The only exception was to go to church or the doctor, and so far, the only thing I’d done was go to the doctor.

“But I told him that this meeting was like going to church for me, and he said we’d consider it church. So I went.”

Hooper stood at the podium on one leg and urged the council to pass a resolution opposing offshore drilling. She was one of several people the council allowed, unexpectedly, to speak on a night that was supposed to include only a two-minute pitch for the resolution by one spokesperson.

“I was shaking,” she said. “You know how hard it is to stand on one leg for 20 minutes?”

But when Hooper and the others finished talking and answering questions from the council, the panel became the latest local government body along the coast to adopt the anti-drilling and anti-seismic testing resolution. And it had done so unanimously, even though several members had expressed at least some interest in delaying the vote, and a couple later said they felt pressured.

Supporter Spotlight

Hooper, who had organized the group of 85 who applied that pressure – a bunch simply named “Concerned Citizens” because they’re concerned about more than just offshore oil – won’t apologize.

“We were only supposed to be allowed one speaker, but the council – Mayor Jerry Jones – opened it up,” she recalled. “After (designated speaker) Jess Hawkins, every one of our speakers talked off-the-cuff. It was people, educated about the facts, speaking to their elected representatives. That IS Democracy. And I have to give the city council a lot of credit. They listened, and they made a decision. They had three who could have tabled it, but they didn’t.”

So maybe, just maybe, Penny Hooper was supposed to be there that Tuesday night. Maybe – she mentioned it half-jokingly – maybe she was supposed to have suffered that broken femur. After all, even though she’s a longtime environmental advocate and had been active in anti-drilling, pro-alternative energy efforts for years, even before it seemed altogether necessary in North Carolina, she might not have had the time to do all the organizing if she’d been able to be her normal hyperactive self. She was stuck in what she calls the Lazy-Boy command center for weeks, and what else was she going to do but fire off hundreds of emails and make countless phone calls to drum up and organize support for the resolution?

“Anybody who knows me knows I’m not the type to sit around and watch old movies and eat bon-bons,” Hooper said. “So this gave me something to do, something to feel useful. Without it, I’d have gone stark-raving mad.”

In a way, though, it seems like Hooper’s whole life story conspired to put her there, first in the recliner, then in the council chambers.

Born in Indiana, Penny Widell earned her undergraduate college degree from Purdue. But she knew she loved the ocean, so she headed to the University of Southern California and its marine laboratory on Catalina Island for graduate school, where she earned her master’s degree in hyperbaric physiology – the study of what happens to the body when it’s under pressure, as in diving – and met husband-to-be, Mark Hooper, who was a grad student from New York, studying oceanography.

Diving, she said, only enhanced her love of the ocean and stoked the fire to protect it. And Mark Hooper?

“Well, it was very isolated out on Catalina Island, and there were only 14 students. You either fell in love or got divorced. We fell in love, became diving buddies, stayed together, and got married in 1974.” They became a lifelong team, sharing everything they did, and still do.

Mark decided he didn’t want to be an oceanographer, because, well, they aren’t on the water enough. He decided to become a commercial fisherman. When she earned her master’s degree, Penny got a job at Duke University in Durham at one of the few hyperbaric chambers in the country, working on a program funded by a Florida-based foundation. Mark went along. The program got cancelled, and it was either move to Panama City, Fla. – three weeks before their wedding was scheduled – or quit. Penny quit. She and Mark took off on a pre-honeymoon tour, all the way down the East Coast and back, scouting places to live.

Her parents had died and left her some money and a house, which they could sell. The couple’s main location criterion was obviously proximity to water.

Beaufort fit the bill. Mark talked to a guy at the dock who said he’d hire him as a mate on a shrimp trawler. They bought a rundown house at the corner of Turner and Broad streets — which turned out to be historic — and Mark could walk to the boat from there. The house had 11 rooms, which seemed a bit much for a young couple, but it was cheap. Beaufort wasn’t really BEAUFORT in 1974, and the house had an apartment, and the apartment paid the mortgage.

Only one problem. Mark got seasick. He stuck with it for a while, but eventually decided he needed to be a different kind of commercial fisherman. Soft crabs seemed like the ticket. So they sold the big house – Beaufort by now was booming, thanks to a waterfront renewal project that was the success of all successes – so they tripled their investment and found acreage in Smyrna. It had plenty of room for Penny’s pottery studio – that’s how she made her share of their living (Mark helped) – and had the clean water and boat basin necessary for crab shedding.

The house was a bit isolated – Smyrna’s in “Down East” Carteret County, 30 miles from Morehead City – but it was passive solar, so the electric bills were low, and they eventually added solar panels, which further lowered those bills. They lived simply – walking the environmental walk – but eventually it came time for kids to go to college. Big bills. Penny began using that master’s degree as a biology instructor at Carteret Community College and eventually headed the department.

All this time, both Hoopers had benefited from a couple – Mark’s parents, Irv and Nicki, both now deceased – that Penny calls Mom and Dad. She’d lost her parents so young, before she turned 22, and Irv and Nicki were so remarkable and were great role models. A biochemist, Irv had retired at age 55 and moved to Carteret County, where he worked at the Duke Marine Lab part-time and founded the county’s first environmental group, Carteret County Crossroads, in 1979. Penny and Mark, always a team, also worked there for a time, under a marine ecologist.

They joined the Unitarian Coastal Fellowship in Morehead City, and became deeply involved with a faith that stresses the “interdependent web of all existence.” Penny eventually became head of the fellowship’s Green Sanctuary program, deepening that love of the ocean that had existed since her first dive revealed the magic and beauty beneath the surface.

She also got involved in Interfaith Power and Light, locally and nationally, through the church. And eventually she organized the local Hands-Across-the Sand effort, which together with others across the country, annually links bodies on the beach, each one protesting oil and gas drilling. It didn’t seem so urgent in North Carolina until President Obama in January proposed to open much of the East Coast, including North Carolina, to drilling.

This year, the local Hands effort in May burgeoned to more than 100 people, many of whom stayed after for a presentation by Zach Keith, an organizer from the N.C. Sierra Club office. The enthusiasm led to well-attended meetings in June at the Morehead City Train Depot, where the group, coming to be known simply as “Concerned Citizens,” formed subgroups, including one that took responsibility to write letters to newspapers and one to circulate a letter for businesses to sign and send to Gov. Pat McCrory. Hooper and others got 120 businesses to sign, and they knew then that they had something.

Throughout the summer, Hooper had been deeply involved with spiritual-based environmental matters, attending the Unitarian Universalist Association’s General Assembly and a national meeting of Interfaith Power and Light. The spiritual basis for environmental protection infused her message more and more. She noted the stands for the environment taken by Pope Francis, and she increasingly heeded her realization that the best way to reach the undecided is through the heart, not just through facts.

“I realized we’re not going to win people with nothing but facts and numbers,” Hooper said. “That was the big shift for me. It’s not that I don’t know the science and the facts, it’s just that people relate better when you talk about things that are close to their heart.

“You talk about their experiences swimming or boating in Core Sound. That’s not going to happen if there’s an oil spill. And you talk to people about the kind of world we’re going to leave for our grandchildren. What’s Cape Lookout going to look like with oil on the beach? You talk to them about things they love. It feels better and works better than just quoting facts to try to rebuke the garbage science (the supporters of offshore drilling) put out.”

What it boils down to, really, is a world view, though, and Hooper now is a big proponent of a question posed by Mary Evelyn Tucker, a Yale professor who spoke to the national Interfaith Power and Light gathering this past spring.

She’s a Senior Lecturer and Research Scholar at Yale, where she has appointments in the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies as well as the Divinity School and the Department of Religious Studies and directs the Forum on Religion and Ecology with her husband, John Grim. Tucker, Hooper said, put it this way: “Do we look at our world as a commodity or as a community?”

In U.S. environmental circles, it’s a point of view that goes back to Aldo Leopold, author of the seminal book, A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949. Leopold was talking abound land, and he put it this way: “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

But it’s at least equally true of the sea, Hooper said, and she has known that intuitively since her first scuba dive.

“It’s 70 percent of the planet,” she said, “and it’s under assault from every direction. It needs to be protected more than ever. All energy extraction comes with a cost. The question is what cost are we willing to pay?”