NAVASSA – More than $10 million has been allocated to clean up the site of a former wood treatment plant in this Brunswick County town following a federal lawsuit that resulted in the largest environmental settlement in U.S. history.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources have received more than $13 million to restore natural resources damaged from years of operation of a creosote plant, NOAA announced yesterday.

Supporter Spotlight

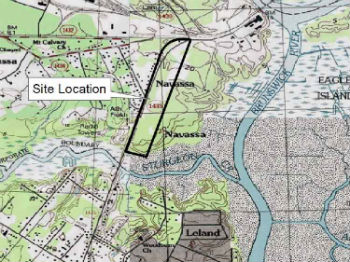

The 292-acre tract was the site of a large plant that operated for nearly four decades treating wood with creosote, a common wood preservative made from a wide range of chemicals that, when combined, form a gummy substance applied to wood products such as railroad ties and telephone poles.

The Navassa site was added to the EPA’s list of Superfund sites in early 2010, about four years before a New York district court judge approved a $5.15 billion settlement between the U.S. Department of Justice and the Anadarko Petroleum Corporation.

That amount was split between dozens of sites in more than 20 states. NOAA expects an additional $9 million will be funneled to clean up and restore the Navassa site.

“We have not received the money yet,” said Michel Gielazyn, regional resource coordinator in NOAA’s Charleston, S.C., office. “It takes a little while for it to trickle down.”

She said she hopes trustees will receive the funds in the next few weeks.

Supporter Spotlight

More than $4.2 million has been allocated to studies and cleanup at the site and an additional $917,732 to remedy damages to natural resources in the area.

“Coastal wetlands like the areas impacted in North Carolina provide important environmental and economic services,” W. Russell Callender, acting assistant NOAA administrator for the National Ocean Service, said in a statement. “Using these funds to restore habitat will benefit fisheries and wildlife and provide protection from storms, all of which will directly benefit the coastal communities and economies that depend upon them, while improving coastal resilience.”

With input from the public, a possible multi-year restoration effort will include restoring and protecting wetlands, river and estuary habitats of the Cape Fear River watershed.

“The trustees are currently meeting and discussing types of restoration projects that we think would restore the injury that occurred at the site,” said Howard Schnabolk, a habitat restoration specialist with NOAA.

A public meeting to discuss possible projects will eventually be held, he said. The meeting will give town residents and the general public the opportunity to share restoration ideas.

“We’ve just been in real early preliminary talks about it and don’t have a schedule,” Schnabolk said. “The trustees will eventually put together a restoration plan that will detail the process.”

Similar to an environmental impact statement process, a draft of the restoration plan will be released to the public. The public will get the opportunity to comment on the draft.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service and the other trustees look forward to talking with citizens, restoring the natural resources impacted in this watershed and improving water quality and habitat for the people and the fish and wildlife that depend on them,” Cindy Dohner, the southeast regional director for Fish and Wildlife, said in a statement.

The plant opened in Navassa in 1936 under the ownership of the Gulf States Creosoting Co. and was sold to Kerr-McGee Chemical Corporation in 1965.

Kerr-McGee closed the plant in 1974, leaving behind extensive creosote contamination, a determination made in a 2005 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-enforced study.

Since then, ongoing studies have been conducted on the site in the small town near Wilmington to determine remediation options and public health effects.

Creosote has been classified as a probable carcinogen by the EPA, with studies showing an increased risk of cancer and respiratory problems in plant workers routinely exposed to the material.

The EPA and the Multistate Environmental Response Trust, which owns and manages more than 400 former Kerr-McGee sites in 24 states, in 2011 collected samples of soil, Sturgeon Creek marsh sediments, surface water and groundwater at the Navassa site.

Samples turned up hazardous substances, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a combination of chemicals that commonly enter the body through breathing contaminated air or by consuming contaminated water or food.

A N.C. Division of Public Health assessment, released in 2012, found that the creosote contamination did not present a threat through contact or public drinking water. That same report went on to say that further studies were needed to determine whether fish and shellfish in nearby waters were contaminated.

Consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish would directly expose humans to the contaminants.

Trustees must follow certain criteria in restoration projects, including trying to replace the types of services lost from contamination.

“Again, it’s real early to say specifically what would occur,” Schnabolk said. “That question is exactly what the public will be allowed to weigh in on.”