Commercial wind farms off the N.C. coast will likely have little effect on birds, bats, fish and most marine mammals, noted a federal assessment of the possible environmental and social effects of developing wind energy off the coast.

The assessment, a giant step forward in the long process of developing offshore wind energy, was released a few weeks ago by Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, the federal agency that regulates offshore energy development beyond the states’ three-mile limit.

Supporter Spotlight

The 300-page assessment supports the potential lease sale of about 200 square miles in three areas of the N.C. coast: one off Kitty Hawk and two off Cape Fear near Wilmington. No wind farms have yet been built in U.S. waters.

BOEM will hold three public hearings this week on the assessment. The first is today at the Hilton Garden Inn in Kitty Hawk. Others are scheduled for Wednesday at the Coastline Conference and Event Center in Wilmington and Thursday at the South Brunswick Islands Center in Carolina Shores. All hearings begin at 5 p.m.

The three areas are all that’s left of the more than 2,800 square miles of N.C. coastal waters that BOEM and a task force of federal officials and state and local leaders began studying three years ago for wind development. Most areas were eliminated to protect important viewsheds, sensitive habitats and resources or to minimize conflicts with other activities such as military operations, shipping and fishing.

After that winnowing, BOEM in 2012 announced possible lease sales for about 1,400 square miles in six areas off the coast. The environmental assessment further reduced the area after the Coast Guard and shipping interests voiced concerns about interference with some shipping lanes. At the mouth of Cape Fear River, the proposed lease areas designated as Wilmington West and Wilmington East are adjacent to some of the busiest shipping lanes in North Carolina, which led to some reduction in the size of the fields. Visual impacts also reduced the size of one area.

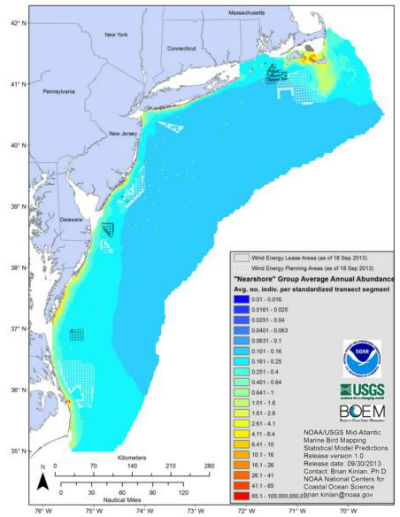

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service then recommended that some areas be reduced to protect migratory and pelagic birds. Bird strikes have been the major environmental effect of onshore wind towers. The BOEM assessment notes that offshore towers should have less of an effect because not many birds fly far from shore. Songbirds, for instance, usually stick close to the coastline on their nocturnal migrations, but they could be pushed farther from shore by storms and forced to fly at lower altitudes, making them prone to strikes. Many of the species are in trouble in North America and even a few fatalities could be deemed unacceptable.

Supporter Spotlight

John Stanton, project leader and senior biologist for the Fish and Wildlife Service in Columbia, has been studying flight patterns of nearshore birds, especially sea ducks, for years. “For sea ducks, they fly almost 20 miles offshore,” he said. “Zero to 20 miles. We were able to suggest that that was important to BOEM. Visual states and sea ducks seem to complement each other.”

Kitty Hawk asked BOEM that the proposed lease area off the northern Outer Banks be moved farther offshore to avoid visual impacts. So did the National Park Service, which wanted the lease area moved 33 miles from its national seashore at Cape Hatteras.

The visual effects of utility-scale wind towers have been a major obstacle on land. People just think they’re ugly. In the water, the massive wind towers take up as much vertical space as a Boeing 747. Towers usually range 200-300 feet tall. Three blades extend another 100 feet up from the turbine’s hub

Given those dimensions, it may be understandable why Kitty Hawk and the park service objected. But the resulting reduction in area forces Harvey Seim to question the viability of commercial wind energy off the N.C. coast. He is a professor of marine sciences at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and led a team of university researchers who in 2009 finished a seminal report on offshore wind energy in North Carolina.

“This is a tremendous reduction,” he says. “The area that is left is now a very small fraction of the area that was identified.”

Seim points to an evaluation process that did not give adequate notice for public input. “There have been no large public discussions,” he says. “The decisions were made without any give or take.”

Like the UNC study, BOEM’s assessment predicts that offshore wind turbines will have little effect on bats, which are a surprising casualty of onshore towers. They’re struck by the blades or are killed by the changes in air pressure caused by the turning blades. All species of bats on the East Coast feed on insects, though, and few bugs venture far from shore. The BOEM study recommends that the turbines have night lighting in colors and patterns that won’t attract insects so bats won’t be tempted to follow their prey offshore.

BOEM, also like the UNC researchers, doesn’t think the offshore turbines will have much of an adverse effect on marine mammals like porpoises and whales. One of the proposed areas near Cape Fear, the federal assessment notes, may have to be reconfigured to avoid known paths of migrating right whales.

Ships used in building the wind towers pose the biggest threat to marine mammals, both studies note. Propeller strikes and the effects of construction noise could be minimized by employing observers on the ships and requiring that construction be limited to late spring and summer when whales aren’t normally migrating off the N.C. coast.

Despite its reduced size, the Kitty Hawk lease area still has allure. Michael Thompson, manager of State Affairs for Dominion North Carolina Power, said in an email that the company is still interested in its potential and is reviewing the assessment. Dominion provides electricity to much of northeastern North Carolina.

Dominion’s interest is significant. The UNC study noted that there are no transmission lines on the Outer Banks capable of handling the amount of energy generated by utility-scale production of wind energy, and that has not changed since the report’s release.

Dominion’s corporate parent, Dominion Virginia Power, is based in Richmond, Va. It has leased an area off the Virginia coast, about 20 nautical miles to the north of the Kitty Hawk site. The 2,000 megawatts that turbines off Kitty Hawk would produce at peak generation could be transmitted to Dominion’s towers off Virginia.

Thompson didn’t rule out linking the two sites. “DVP will evaluate the final call area, environmental impacts, robustness of the transmission system and several other factors before determining an interconnection location,” he wrote.