Chris Jordan photographed this tragic albatross chick that died from eating plastic garbage fed to it by its parents. The parents pick up the garbage from the polluted ocean surrounding the Midway Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, 2,000 miles from the nearest people. Chris Jordan photographed this tragic albatross chick that died from eating plastic garbage fed to it by its parents. The parents pick up the garbage from the polluted ocean surrounding the Midway Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, 2,000 miles from the nearest people.

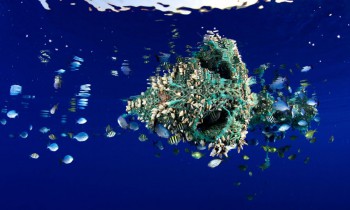

A Heavy Toll on WildlifeFrom the Center of Biological Diversity Supporter SpotlightThousands of animals, from small finches to great white sharks, die grisly deaths from eating and getting caught in plastic. Fish in the North Pacific ingest 12,000 to 24,000 tons of plastic each year, which can cause intestinal injury and death and transfers plastic up the food chain to bigger fish and marine mammals. Sea turtles also mistake floating plastic garbage for food. While plastic bags are the most commonly ingested item, loggerhead sea turtles have been found with soft plastic, ropes, Styrofoam and monofilament lines in their stomachs. Ingestion of plastic can lead to blockage in the gut, ulceration, internal perforation and death. Even if their organs remain intact, turtles may suffer from false sensations of satiation and slow or halt reproduction. Seabirds by the hundreds of thousands ingest plastic every year. Plastic ingestion reduces the storage volume of the stomach, causing birds to consume less food and ultimately starve. Nearly all Laysan albatross chicks — 97.5 percent — have plastic pieces in their stomachs. Their parents feed them plastic particles mistaken for food. Based on the amount of plastic found in seabird stomachs, the amount of garbage in our oceans has rapidly increased in the past 40 years. Marine mammals ingest and get tangled in plastic. Large amounts of plastic debris have been found in the habitat of endangered Hawaiian monk seals, including in areas that serve as pup nurseries. Entanglement deaths are severely undermining recovery efforts of this seal, which is already on the brink of extinction. Entanglement in plastic debris has also led to injury and mortality in the endangered Steller sea lion, with packing bands the most common entangling material. In 2008 two sperm whales were found stranded along the California coast with large amounts of fishing net scraps, rope and other plastic debris in their stomachs. |

OCRACOKE — Paddling along the shoreline of Ocracoke Island a few weeks ago, I saw what looked like an armor-clad knight waving from a hummock of spartina grass. I stopped and stared in shock, then bewilderment.

Supporter Spotlight

I looked through my binoculars and realized I was looking at a group of silvery helium balloons, tied together, caught in the branches of a small dead cedar tree and swaying in the sea breeze. These balloons, which would probably find their way into Pamlico Sound, were part of a huge and ever-increasing problem threatening North Carolina’s marine environment: plastic pollution.

When balloons fall into the water they resemble jellyfish, which are a favorite food of sea turtles. When they mistakenly eat them, the sea turtles die. Plastic bags and bottles can be equally deadly to marine life.

Off the coast of North Carolina lies what is known as the North Atlantic Gyre. It’s a large system of rotating ocean currents, often driven by strong winds, that’s centered near Bermuda. It includes the Sargasso Sea and the Gulf Stream. Within its center, drawn in by the currents, lies what Lisa Rider, coordinator of the N.C. Marine Debris Symposium, describes as a plastic soup. This floating mass of plastic is not the only area of North Carolina waters that is awash with plastic pollution, however. The waters in our sounds and rivers are also filled with plastic debris, she said.

According to Rider, who is also assistant director of the Onslow County Solid Waste and Landfill Department, plastics are becoming more and more of a problem. Not only bags and bottles, but plastic straws, spoons and fast-food containers add to the deadly mix. Cigarette butts, which contain plastic in their filters, are the majority of the plastic litter, Rider notes. She says that there are no naturally occurring organisms that break down the polymers in plastic, so they never biodegrade. The sun may break them down into tiny pieces called micro-plastics, which makes them even more dangerous because they are then more easily consumed by marine organisms.

The ecological effects of plastic pollution is not the only concern. There are also economic consequences as well. Plastic-littered beaches are not good tourist draws, and boat engines can be fouled by plastic. The commercial fishing industry is affected when consumed plastics move up the food chain to edible fish, reducing the catch. One of the goals of the symposium is to develop an award for businesses that reduce their plastic production and use.

While industrial and agricultural plastics pose problems, the main focus is on what are called “single-use plastics,” particularly plastic drink bottles and plastic bags. According to Ethan Crouch, chairman of the Carolina Beach Plastic Bag Committee, plastic bags have a 20 minute lifespan for consumer use. They are the cause of death, however, for about 100,000 marine mammals each year. The goal of the committee is to educate the community about the problems these bags cause, Crouch said

Scott Mown, who is with the Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Services in the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, oversees the state recycling program. Its main focus, he says, is on plastic bottles. The concern is making sure that plastic bottles and other recyclables are collected and distributed to the recycling centers. Otherwise they end up in the ocean or in land fills. There is a statewide ban on depositing plastic bottles in landfills, but he says that it is very difficult to enforce.

The program encourages community recycling, including curbside collection and, in beach communities, collection bins at beach access roads. They have worked with such seaside communities as Sunset Beach and Indian Beach, but want to expand to other beach towns.

Out of 550 municipalities in the state, 315 now have curbside recycling. Others have drop-off centers where people can deposit their plastics and other recyclables.

Mown added that, while recycling is the main focus, the state also encourage source reduction, which means producing fewer plastics. Among their recommendations is replacing plastic bags with re-usable shopping bags and plastic bottles with refillable water bottles.

Another North Carolina department concerned with plastic pollution is the Division of Coastal Management. Paula Gillikin, a manager at the division’s Coastal Research and National Estuarine Research Reserve, conducts most of her work at the Rachael Carson Preserve, near Beaufort. She focuses on plastics on the shoreline, though they do some underwater cleanup. Most of the plastics, she believes, float to the reserve from other places — washed up from upstream businesses, waterfront homes and blown out of people’s boats. Along with bottles and bags, she notes, much comes from the restaurants, including Styrofoam food containers and plastic forks.

Another North Carolina department concerned with plastic pollution is the Division of Coastal Management. Paula Gillikin, a manager at the division’s Coastal Research and National Estuarine Research Reserve, conducts most of her work at the Rachael Carson Preserve, near Beaufort. She focuses on plastics on the shoreline, though they do some underwater cleanup. Most of the plastics, she believes, float to the reserve from other places — washed up from upstream businesses, waterfront homes and blown out of people’s boats. Along with bottles and bags, she notes, much comes from the restaurants, including Styrofoam food containers and plastic forks.

Gilikin’s group conducts several cleanups a year, trying to use ecosystem-friendly bags and containers, such as bags made from cornstarch instead of plastic. They try to incorporate education into their cleanups and tours. In every cleanup, she noted, they find at least one balloon. A few years ago she and her co-workers conducted a social science survey, to see what users of the Rachael Carson Preserve thought were the most common debris. Bottles and bags came in first. Caps and lids are also common, as well as small pieces of plastic.

Bonnie Monteleone, a marine scientist with the Plastic Ocean Project at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, says that plastics constitute approximately 90 percent of the trash floating in the ocean. Plastic in marine waters, she explains, act like sponges, absorbing PCBs, DDT, and other “nasty chemicals,” many of which are now illegal but still remain in the environment as part of the plastics. Small fish that consume these plastics are eaten by larger fish, which may in turn be eaten by humans. We may inadvertently be consuming toxins which have been prohibited for decades, Monteleone noted.

Her art exhibit made entirely from plastic pulled from the sea can now be seen at UNC Chapel Hill.

A newly released study, conducted by the Natural History Museum at the University of Plymouth in England, found that there was more plastic pollution than previously suspected. According to zoologist Lucy Woodal, “Plastic waste is breaking down into fibers, invisible to the naked eye, and sinking to the sea floor. The number of fibers near the ocean bottom is up to four times greater than in shallow or coastal waters.”

More than half of these fibers, she noted, are rayon, with polyester, polyamides, acetate and acrylic making up most of the rest. Scientists estimate that there are a total of 269,000 tons of plastics in the world’s oceans.

Thinking about the disturbing statistics, I paddled my kayak to the shore. I pulled it on the sand and trudged through the grass and debris to the balloon-ensconced tree. Along the way I also picked up a plastic water bottle and a broken Styrofoam container, both cushioned in the grasses. I pulled the balloons down and stashed them in the bow of the kayak before continuing on. It wasn’t much, but at least I had taken a small step in reducing the pollution, and maybe saving an animal’s life.